Women of Wisdom,

Women of Power

Commemorative Reflection on the Lunar Anniversary of the Parinibbāna of Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī Therī, Founding Mother of the Bhikkhunī Sangha

by Tathālokā Therī

Women of Wisdom,

Women of Power

Commemorative Reflection on the Lunar Anniversary of the Parinibbāna of Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī Therī, Founding Mother of the Bhikkhunī Sangha

by Tathālokā Therī

May all be at ease. May all know the bliss and peace of Nibbāna.

This February full moon, in ancient Buddhist texts, is associated with one of the great mothers in Buddhism, Mahā Pajāpatī “The Great Leader” Gotamī. Not only does Mahā Gotamī have the very special role and distinction of being the woman who nurtured and raised the Buddha Gotama, the sage of the Sakyan clan. For some faiths, this would be enough. But not for Buddhism. For her, she has a further and extra-ordinary special distinctions. Not only was she a faithful follower and devotee of the sage, her son. Rather, she led a very large following forth and petitioned—in all tales finally, successfully—for these women’s full entry and full acceptance into the shared base of training, quite literally upasampadā. For this is the meaning of the word which we use for “full ordination” or “higher ordination.”

It didn’t stop there. Not only did she become a fully awakened one, an arahantā sāvikā buddhā, herself. She did so together with many other women; both her peers and her students. Early Buddhism had space for this.

Among the ancient bhikkhunī therīs who are said to have large followings, in the Pāli-text Therīgāthā’s songs of enlightenment of the women elders, and in their sacred biographies in the Therī-apadāna we find: the great leader Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī, holder of the discipline Pātācārā, the Buddha’s wife Yasodhārā, and the renounced queen Anojā—all are said to have had very large followings themselves, communities of their own within the greater Buddhist community, of which they themselves were the teachers, leaders, and preceptors.

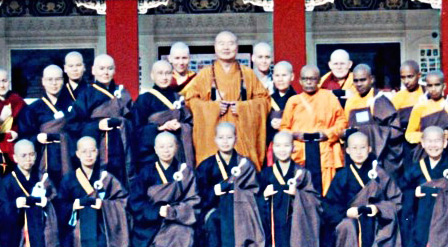

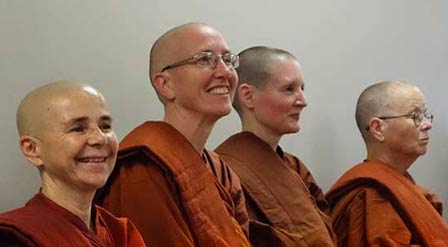

Mahapajapati Gotami

For the greater Buddhist community too, both Mahāpajāpatī and the Buddha himself had plenty of free space for even more capable and awakened women of a variety of ethnicities and nationalities to attain rank and leadership. The Buddha placed two more eminent and outstanding women disciples, those commended by him as foremost in wisdom and foremost in spiritual power, together in key positions of leadership, pointing to them as exemplars for every Buddhists’ daughter. These were the bhikkhunīs Khemā and Uppalavāṇṇā.

Once someone joked to me upon hearing this that it took two women to be in that role as leading great disciples, where it would have taken only one man. But they did not know the story! Khemā and Uppalavāṇṇā were placed in these roles in parallel to those of the Buddha’s two chief male disciples, Sāriputta, among the bhikkhus also foremost in wisdom, and Mahā Moggālāna, among the bhikkhus also foremost in spiritual power. And, the Buddha had many more excellent and unique awakened male and female disciples—it didn’t end there. Truly, he invested in the Sangha.

The unfolding of the world this year leads me to a reflection about these three qualities and women’s proper qualities in Buddhism, in the Awakened Ones’ minds. Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī: Great Women in Leadership. Mahāpaññā Khemā: Women of Great Wisdom. Mahābhiññā Uppalavāṇṇā: Women of Great Spiritual Power. Awesome. What it must be to have such a heart-mind as to wholeheartedly welcome these qualities, and to really fully appreciate them. To nurture, cultivate, support and extoll them.

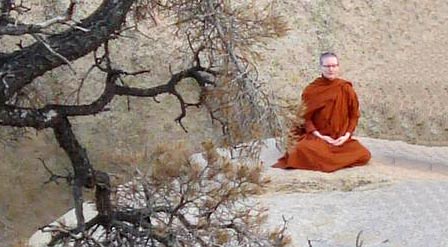

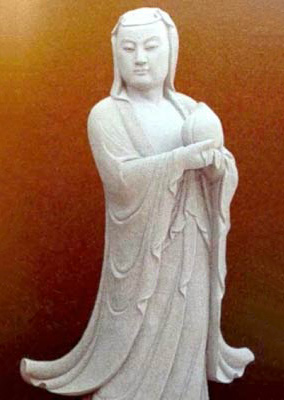

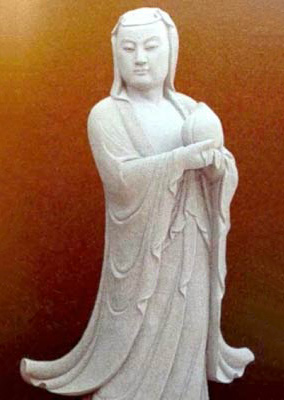

This image of the eminent bhikkhuni disciple of the Buddha, Uppalavanna Theri, foremost in spiritual power, whom the Buddha called his “daughter”, was taken in the arahats garden at Fo Guang Shan in Taiwan.

Not a fear-based reaction, not a desire-based reaction, not an aversion-based reaction, not an ignorance- or delusion-based reaction. A reaction in which the masculine and the feminine are safe in themselves, safe in oneself. Not at war, but at peace. Not competing, but vital, integral aspects of the whole. It is mind-opening, heart-opening. It is a lamp, and illuminates the way. As people often said upon encountering the Buddha: “like a lamp in the darkness,” “like something that was upside down that has been turned upright.” Oh, it feels like this!

These are basic essential teachings in Early Buddhism, the essential heart paradigm, and it would do well for us to see them clearly and hold them as values. With clear sight and deep understanding, we see the way of this enlightened and enlightening, awakened and awakening, Path. As in our chanting: kamalaṃ vā suro, “like the sun awakening the lotus.” “I bow my head to that peaceful chief of conquerors,” “I bow my head to this Sangha,” “I bow my head to this truth.”

“Bowing our head” here means a reverence. It means to let go, to release. A reorientation. To release so many other ways of being, so many conflicts, so many struggles, so many stories—of a whole world and all the ages. To let ourselves come to rebalance, in truth, in clarity, with the way clear in us. It also means standing tall and relaxed in our own integrity—against the stream.

“Against the stream” means that there are many people, really many patterns, otherwise. But the stream of the Dhamma, the Dhammasotā, is different than that. Entering into the stream of the Dhamma, as the Great Leader Gotamī did even as a laywoman householder before entering monastic life, one feels and knows the flow of the Dhamma, the direction of the Dhamma, the grain of the Dhamma, in one’s whole being. It would be contrary to one’s own natural sensibilities then to just continue to muck and muddle around in the same old way.

One of the amazing things about Buddhism is that these saints did not just rapture out. After awakening, they stayed living in the world, immersed in the world, but engaged in it in a very different sort of way.

The Great Leader Gotamī even did so for a very extraordinarily long time. For she lived nearly as long as her adoptive son, the Buddha, only passing into final nirvāna (pārinibbāna) just three months before him, at the very ripe old age of 120.

There is a story within a story in the canonical Pāli-text Gotamī Therī Apadāna, which relates Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī’s final passing. It is called the “Story of the Buddha’s Sneeze.” Mahā Gotamī (as she is called there) goes with a large retinue of her bhikkhunī peers and followers to let the Buddha know that the time has come, and she intends to pass into final nibbāna. At one point in their conversation the Buddha sneezes, and she blesses him, but rather than saying “bless you!”, according to custom, she wishes him “long life!”. But he replies to her that this is not how to bless or pay homage to a buddha. She asks “then how?”. His answer:

Āraddhavīriye pahitatte,

niccaṃ daḷhaparakkame;

Ardent and valiant in applying yourselves intently to release,

Forever steady and with firm resolve in crossing over:

Samagge sāvake passa,

etaṃ buddhānavandanaṃ.

Seeing the Sangha practicing thus in harmony together—

This is how to bless and pay homage to the Buddhas.

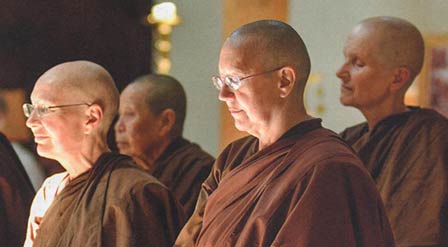

Bhikkhuni Khema

Our Buddha, always thinking of the Sangha…

even when the woman who nursed and raised him is going to pass away that very day. But, this is clear sight. It is very important to think of the community, and to steady a community in its values when a great leader passes away, or when there are important changes in leadership.

It wasn’t that he didn’t care or didn’t take care of her. In fact, the Buddha mentions at this point, in several of the texts, that the final nibbāna of Gotamī’s is even more illustrious even than his own or any of his other great disciples.

All the bhikkhus were called to join in, and the Buddha himself headed up Mahā Gotamī’s funeral procession, with her sārirā crematory remains placed in his own alms bowl while he spoke her eulogy. He himself then gave her relics over to the care of local Licchavi princes of Vesāli who built stupas to commemorate her and enshrine both her crematory remains and those of her many awakened bhikkhunī companions who chose to also attain final nibbāna with her.

It was a great “going out” as the Buddha said: “like stars at dawn they vanish, leaving no trace.” And yet we know the stars at dawn are not truly absent. Which reminds us of the Buddha’s words with regards to buddhas’ and arahants’ parinibbāna: it is not proper to say they are either “existent” or “non-existent” after their death. Not even proper to say “both” or “neither.” Leaving us with—

An opening of mind into the inconceivable.

A doorway forever open to those to whom it is pointed out,

To those who see and know it.

To those whose hearts know the value of non-grasping, and

The joy of Release—

Releasing into Freedom.

And, into that great stance of the arahants.

A suitable way to end on the lunar commemorative day of the final nirvana of the great leader Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī together with many of the foremost early leading women in Buddhism.

May the good that we have gained not be lost.

And may we enter into that peaceful state,

Of all those who abide in the great stream of the Dhamma.

in Dedication & Gratitude

to all those excellent women leaders and teachers,

recluses and sage

of the past and present,

of great wisdom and great spiritual power

may their Way not be lost on us.

For Further Study

More writings by Ayyā Tathālokā related to this topic

- “Going Forth & Going Out: the Parinibbāna of Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī” Dhammadharini (2012, 2015)

- “Lasting Inspiration: A Look into the Guiding and Determining Mental and Emotional States of Liberated Arahant Women in Their Path of Practice and its Fulfillment as Expressed in the Sacred Biographies of the Therī Apadāna” Present (2012)

- “The Amazing Transformations of Arahant Theri Uppalavanna” Present (2011)

On the final passing (parinibbāna) of Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī

- Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā’s “The Parinivāṇa of Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī and Her Followers in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya [Part 1]” (2015a)

- “The Funeral of Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī and Her Followers in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya [Part 2]” (2016)

- Jonathan Walter’s “A Voice from the Silence: the Buddha’s Mother’s Story,” University of Chicago (1994)

On parallel roles for women in early Indian Buddhism

- Peter Skilling’s “Nuns, Laywomen, Donors, Goddesses: Female Roles in Early Indian Buddhism” JIBS (2001)

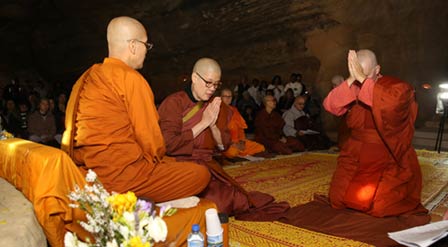

Header photo: This image of the eminent bhikkhuni disciple of the Buddha, Mahapajapati Gotami Theri, founding mother of the Bhikkhuni Sangha and foster mother of the Buddha, was taken in the arahats garden at Fo Guang Shan in Taiwan.

May all be at ease. May all know the bliss and peace of Nibbāna.

This February full moon, in ancient Buddhist texts, is associated with one of the great mothers in Buddhism, Mahā Pajāpatī “The Great Leader” Gotamī. Not only does Mahā Gotamī have the very special role and distinction of being the woman who nurtured and raised the Buddha Gotama, the sage of the Sakyan clan. For some faiths, this would be enough. But not for Buddhism. For her, she has a further and extra-ordinary special distinctions. Not only was she a faithful follower and devotee of the sage, her son. Rather, she led a very large following forth and petitioned—in all tales finally, successfully—for these women’s full entry and full acceptance into the shared base of training, quite literally upasampadā. For this is the meaning of the word which we use for “full ordination” or “higher ordination.”

It didn’t stop there. Not only did she become a fully awakened one, an arahantā sāvikā buddhā, herself. She did so together with many other women; both her peers and her students. Early Buddhism had space for this.

Among the ancient bhikkhunī therīs who are said to have large followings, in the Pāli-text Therīgāthā’s songs of enlightenment of the women elders, and in their sacred biographies in the Therī-apadāna we find: the great leader Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī, holder of the discipline Pātācārā, the Buddha’s wife Yasodhārā, and the renounced queen Anojā—all are said to have had very large followings themselves, communities of their own within the greater Buddhist community, of which they themselves were the teachers, leaders, and preceptors.

Mahapajapati Gotami

For the greater Buddhist community too, both Mahāpajāpatī and the Buddha himself had plenty of free space for even more capable and awakened women of a variety of ethnicities and nationalities to attain rank and leadership. The Buddha placed two more eminent and outstanding women disciples, those commended by him as foremost in wisdom and foremost in spiritual power, together in key positions of leadership, pointing to them as exemplars for every Buddhists’ daughter. These were the bhikkhunīs Khemā and Uppalavāṇṇā.

Once someone joked to me upon hearing this that it took two women to be in that role as leading great disciples, where it would have taken only one man. But they did not know the story! Khemā and Uppalavāṇṇā were placed in these roles in parallel to those of the Buddha’s two chief male disciples, Sāriputta, among the bhikkhus also foremost in wisdom, and Mahā Moggālāna, among the bhikkhus also foremost in spiritual power. And, the Buddha had many more excellent and unique awakened male and female disciples—it didn’t end there. Truly, he invested in the Sangha.

The unfolding of the world this year leads me to a reflection about these three qualities and women’s proper qualities in Buddhism, in the Awakened Ones’ minds. Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī: Great Women in Leadership. Mahāpaññā Khemā: Women of Great Wisdom. Mahābhiññā Uppalavāṇṇā: Women of Great Spiritual Power. Awesome. What it must be to have such a heart-mind as to wholeheartedly welcome these qualities, and to really fully appreciate them. To nurture, cultivate, support and extoll them.

This image of the eminent bhikkhuni disciple of the Buddha, Uppalavanna Theri, foremost in spiritual power, whom the Buddha called his “daughter”, was taken in the arahats garden at Fo Guang Shan in Taiwan.

Not a fear-based reaction, not a desire-based reaction, not an aversion-based reaction, not an ignorance- or delusion-based reaction. A reaction in which the masculine and the feminine are safe in themselves, safe in oneself. Not at war, but at peace. Not competing, but vital, integral aspects of the whole. It is mind-opening, heart-opening. It is a lamp, and illuminates the way. As people often said upon encountering the Buddha: “like a lamp in the darkness,” “like something that was upside down that has been turned upright.” Oh, it feels like this!

These are basic essential teachings in Early Buddhism, the essential heart paradigm, and it would do well for us to see them clearly and hold them as values. With clear sight and deep understanding, we see the way of this enlightened and enlightening, awakened and awakening, Path. As in our chanting: kamalaṃ vā suro, “like the sun awakening the lotus.” “I bow my head to that peaceful chief of conquerors,” “I bow my head to this Sangha,” “I bow my head to this truth.”

“Bowing our head” here means a reverence. It means to let go, to release. A reorientation. To release so many other ways of being, so many conflicts, so many struggles, so many stories—of a whole world and all the ages. To let ourselves come to rebalance, in truth, in clarity, with the way clear in us. It also means standing tall and relaxed in our own integrity—against the stream.

“Against the stream” means that there are many people, really many patterns, otherwise. But the stream of the Dhamma, the Dhammasotā, is different than that. Entering into the stream of the Dhamma, as the Great Leader Gotamī did even as a laywoman householder before entering monastic life, one feels and knows the flow of the Dhamma, the direction of the Dhamma, the grain of the Dhamma, in one’s whole being. It would be contrary to one’s own natural sensibilities then to just continue to muck and muddle around in the same old way.

One of the amazing things about Buddhism is that these saints did not just rapture out. After awakening, they stayed living in the world, immersed in the world, but engaged in it in a very different sort of way.

The Great Leader Gotamī even did so for a very extraordinarily long time. For she lived nearly as long as her adoptive son, the Buddha, only passing into final nirvāna (pārinibbāna) just three months before him, at the very ripe old age of 120.

There is a story within a story in the canonical Pāli-text Gotamī Therī Apadāna, which relates Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī’s final passing. It is called the “Story of the Buddha’s Sneeze.” Mahā Gotamī (as she is called there) goes with a large retinue of her bhikkhunī peers and followers to let the Buddha know that the time has come, and she intends to pass into final nibbāna. At one point in their conversation the Buddha sneezes, and she blesses him, but rather than saying “bless you!”, according to custom, she wishes him “long life!”. But he replies to her that this is not how to bless or pay homage to a buddha. She asks “then how?”. His answer:

Āraddhavīriye pahitatte,

niccaṃ daḷhaparakkame;

Ardent and valiant in applying yourselves intently to release,

Forever steady and with firm resolve in crossing over:

Samagge sāvake passa,

etaṃ buddhānavandanaṃ.

Seeing the Sangha practicing thus in harmony together—

This is how to bless and pay homage to the Buddhas.

Bhikkhuni Khema

Our Buddha, always thinking of the Sangha…

even when the woman who nursed and raised him is going to pass away that very day. But, this is clear sight. It is very important to think of the community, and to steady a community in its values when a great leader passes away, or when there are important changes in leadership.

It wasn’t that he didn’t care or didn’t take care of her. In fact, the Buddha mentions at this point, in several of the texts, that the final nibbāna of Gotamī’s is even more illustrious even than his own or any of his other great disciples.

All the bhikkhus were called to join in, and the Buddha himself headed up Mahā Gotamī’s funeral procession, with her sārirā crematory remains placed in his own alms bowl while he spoke her eulogy. He himself then gave her relics over to the care of local Licchavi princes of Vesāli who built stupas to commemorate her and enshrine both her crematory remains and those of her many awakened bhikkhunī companions who chose to also attain final nibbāna with her.

It was a great “going out” as the Buddha said: “like stars at dawn they vanish, leaving no trace.” And yet we know the stars at dawn are not truly absent. Which reminds us of the Buddha’s words with regards to buddhas’ and arahants’ parinibbāna: it is not proper to say they are either “existent” or “non-existent” after their death. Not even proper to say “both” or “neither.” Leaving us with—

An opening of mind into the inconceivable.

A doorway forever open to those to whom it is pointed out,

To those who see and know it.

To those whose hearts know the value of non-grasping, and

The joy of Release—

Releasing into Freedom.

And, into that great stance of the arahants.

A suitable way to end on the lunar commemorative day of the final nirvana of the great leader Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī together with many of the foremost early leading women in Buddhism.

May the good that we have gained not be lost.

And may we enter into that peaceful state,

Of all those who abide in the great stream of the Dhamma.

in Dedication & Gratitude

to all those excellent women leaders and teachers,

recluses and sage

of the past and present,

of great wisdom and great spiritual power

may their Way not be lost on us.

For Further Study

More writings by Ayyā Tathālokā related to this topic

- “Going Forth & Going Out: the Parinibbāna of Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī” Dhammadharini (2012, 2015)

- “Lasting Inspiration: A Look into the Guiding and Determining Mental and Emotional States of Liberated Arahant Women in Their Path of Practice and its Fulfillment as Expressed in the Sacred Biographies of the Therī Apadāna” Present (2012)

- “The Amazing Transformations of Arahant Theri Uppalavanna” Present (2011)

On the final passing (parinibbāna) of Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī

- Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā’s “The Parinivāṇa of Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī and Her Followers in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya [Part 1]” (2015a)

- “The Funeral of Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī and Her Followers in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya [Part 2]” (2016)

- Jonathan Walter’s “A Voice from the Silence: the Buddha’s Mother’s Story,” University of Chicago (1994)

On parallel roles for women in early Indian Buddhism

- Peter Skilling’s “Nuns, Laywomen, Donors, Goddesses: Female Roles in Early Indian Buddhism” JIBS (2001)

Header photo: This image of the eminent bhikkhuni disciple of the Buddha, Mahapajapati Gotami Theri, founding mother of the Bhikkhuni Sangha and foster mother of the Buddha, was taken in the arahats garden at Fo Guang Shan in Taiwan.