The Great Inquiry

An Interview with the

Venerable Ayya Tathaaloka

by Jacqueline Kramer

The Great Inquiry

An Interview with the

Venerable Ayya Tathaaloka

by Jacqueline Kramer

From the August 2012 edition of Present

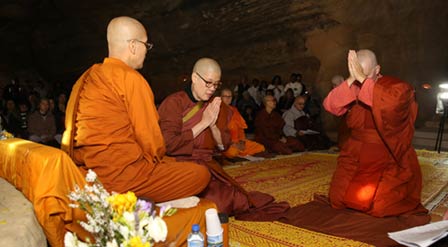

I first met Ayya Tathaaloka when she was in Northern California looking over the land near Jenner that was to become the Aranya Bodhi Forest Hermitage. I had an immediate feeling of sisterhood with Ayya. It turns out that both of us were deeply influenced by her bhikkhuni mentor, the Venerable Myeong Seong of south Korea. The venerable was dedicated to helping rebuild the Bhikkhuni Sangha, and that intention was transmitted to both of us at different times in different ways. Ayya Tathaaloka has bravely and intelligently gone about supporting the growth of the Bhikkhuni Sangha by helping establish the first bhikkhuni forest hermitage in the West, by acting as a preceptor for many Western bhikkhunis, and in many other large and small ways. She has taken great pains to insure recognition of the Bhikkhuni Sangha by careful scholarship and adherence to established procedures.

We spoke again on a sunny May afternoon in 2012, exploring how her early life brought her to the gates of the Bhikkhuni Sangha. The question of how our Western Buddhist pioneers came to the path is an intriguing one. What makes a child from a JudeoChristian culture seek out Buddhism? What sorts of influences and personality traits draw a child to the East? It’s no surprise that an adventuresome, independent spirit and a questioning mind are necessary for the journey. A certain amount of doubt and discomfort are also important catalysts. In this interview we get a glimpse of Ayya Tathaaloka’s adventuresome, independent spirit; her early doubt; and the kind influences that guided her East to Buddhism.

Jacqueline Kramer: What was your first glimmer of Buddhism?

Ayya Tathaaloka: This is a question that other people are able to answer, but I find for myself that I can’t. I don’t remember my first encounter with Buddhism. Growing up, there were books that had things about Buddhism around me. There was also Buddhism in the movies and on TV and magazines like National Geographic. I remember seeing robed Buddhist monks in jungle environments. There are some things I remember from my teenage times that particularly impressed me. Whether you’d say they are connected to Buddhism or not, I’m not sure. I watched the show Kung Fu. David Carradine was playing a man who was a Buddhist novice training with a master and was wandering from place to place in the old Wild West learning various life lessons.

Ayya Tathaaloka: This is a question that other people are able to answer, but I find for myself that I can’t. I don’t remember my first encounter with Buddhism. Growing up, there were books that had things about Buddhism around me. There was also Buddhism in the movies and on TV and magazines like National Geographic. I remember seeing robed Buddhist monks in jungle environments. There are some things I remember from my teenage times that particularly impressed me. Whether you’d say they are connected to Buddhism or not, I’m not sure. I watched the show Kung Fu. David Carradine was playing a man who was a Buddhist novice training with a master and was wandering from place to place in the old Wild West learning various life lessons.

I was discouraged when I asked whether women could ordain and was told that this was a possibility open only for men. To my young teenager’s sense, not knowing much, that seemed very strange to me. That series became a kind of paradigm for me. I understood the pattern that you pick up wisdom from teachers or teachings and then in life circumstances, you reflect on that wisdom and apply that to the circumstances that you’re meeting in life. Then the circumstances themselves have the opportunity for growth or catharsis or reflection. They may become part of your ongoing awakening experience. Those teachings then become relevant, come to life, and become manifest. That’s something that I got from watching that show.

Of course, that’s not the only place I saw that paradigm; it was all around. There was encouragement from my parents to learn and apply what has been learned to life circumstances. So that’s not a new thing, but that show illustrated these lessons and their wisdom in a classical Buddhist context.

The Lord of the Rings and Star Wars also contained deliberate use of archetypical images of Christian and Buddhist monastics, paradigms of forces of good and evil, wise mentors, and the development and cultivation of the acolyte. The disciples were tried and tested, and triumphing over the forces inside themselves was the big issue. The small person who is from nowhere is the one who then triumphs and saves the world. They were archetypes of spiritual seekers.

Also, there were a couple of other things. I remember one friend of the family had gone to Thailand with the Peace Corps. He ordained for three months as a Buddhist monk during the vassa after finishing his assignment. I remember hearing about that experience and finding it very interesting hearing about what it was like and learning that it was possible for a Western person to go and do that. This friend was male and I was interested in whether this would be a possibility for myself or not. It sounded like a really great learning experience. I was looking at my possibilities for higher education at that time. To have that kind of training in sila (virtue) and meditation and wisdom seemed interesting and excellent as compared to university options.

I was discouraged when I asked whether women could do that too and was told that this was a possibility open only for men.

But I was discouraged when I asked whether women could do that too and was told that this was a possibility open only for men. I remember thinking that I had seen some old Buddhist texts and had the idea that women had been ordained in Buddhism in the Buddha’s lifetime. I felt that if the Buddha was truly enlightened, this possibility should be open for women as well. I felt it should be there and that it had been there. It seemed really strange to me that this would not be so in a place where Buddhism was thriving, in an affirmatively Buddhist country. To my young teenager’s sense, not knowing much, that seemed very strange to me.

Not so long after that another family friend who came by to visit had been at Shasta Abbey. I hadn’t heard of Shasta Abbey before. I was living in Washington State and at that time we didn’t have any Buddhist temples or monasteries around that part of the country. But Mt. Shasta was just south of us, not so very far. That friend mentioned that there were both male and female Buddhist monks there. When I heard that, I thought, “Right! That’s how it should be.” I felt this kind of awakening interest then. And I learned there were these differing dynamics about ordination and women being able to ordain or not.

I would say another memorable thing would be a little bit later, still as a teenager, encountering two books that were quite important. One was Master Sheng Yen’s Faith in Mind. It is an English translation of an enlightenment poem by the Third Zen Patriarch in China. I ended up studying and practicing the hua tou with him later.

JK: Where was he?

Doubt can become a hindrance and cause a lot of suffering in our minds. For me, this accumulated doubt was an abiding, underlying pit of suffering.

AT: He was in Taiwan. He also founded the Dharma Drum Buddhist Association Center on the East Coast here in the U.S., and it has a West Coast branch as well. That poem by this old Buddhist master touched me.

Then there was the Blue Cliff Records, the koans. Someone introduced that book to me as a book of Buddhist wisdom because I seemed to be interested in such. I opened it up and began to look at it, and it brought up tremendous doubt in me right away – the underlying doubt about the many things in life and in our world that were always simmering below the surface. We’re skimming on top of that in ordinary life.

JK: Was this like the great doubt that Zen teachers speak of, or was this doubt as in a hindrance?

AT: I think this would be the great doubt that the Zen teachers talk about – deep and fundamental doubt. Touching into and penetrating this is the clearing of a hindrance.

JK: Like what are we doing here?

AT: Yes. Of course, before one has a breakthrough to the great inquiry – what are we doing here? – that and the kind of doubt that is a hindrance in people’s ordinary lives, dance intertwined, intermingled with each other. This is because of not applying that doubt to inquiry in wise ways. When that’s so, doubt can become a hindrance and cause a lot of suffering in our minds. For me, this accumulated doubt was an abiding, underlying pit of suffering. Reading even a few of the koan cases drew it all together into a great mass – like I was a cat that needed to vomit up a fur ball as big as the whole world. This was a great mental energetic mass of everything I had been unable to digest in the whole world because of not having right understanding. At that time, I didn’t know how to see it correctly and penetrate that great mass.

Thinking back I would say those were impressive things, but I don’t remember what the first thing was early on. I know both my mother and my father seemed to have respect for the Buddha.

JK: What religion did you grow up with?

AT: I didn’t grow up with one particular religion. My father was an atheist scientist and his family was not religious. They were a family of engineers, with a lawyer or two. They were into the material world and big into cause-and-effect forensic science, which is an investigative science. I got a kind of religion of science and investigation from them. My mom had a partly Episcopalian background with a large dose of naturalism – love for the natural world. She had studied botany, worked as a naturalist, and ended up doing her Ph.D. in phenomenology, which originated with that name under the German philosopher Heidegger, who studied Yogacara Buddhism, which is also known as Vijñanavada, Cittamatra, or the Mind-Only School of Buddhism. From her I got a great appreciation for the natural world – the human interrelationship with the natural world being, in itself, her sphere of spiritual communion. Then both my parents remarried. My father remarried a Jewish woman and my mom remarried a Muslim man. So that increased the religious diversity in our family quite radically.

AT: I didn’t grow up with one particular religion. My father was an atheist scientist and his family was not religious. They were a family of engineers, with a lawyer or two. They were into the material world and big into cause-and-effect forensic science, which is an investigative science. I got a kind of religion of science and investigation from them. My mom had a partly Episcopalian background with a large dose of naturalism – love for the natural world. She had studied botany, worked as a naturalist, and ended up doing her Ph.D. in phenomenology, which originated with that name under the German philosopher Heidegger, who studied Yogacara Buddhism, which is also known as Vijñanavada, Cittamatra, or the Mind-Only School of Buddhism. From her I got a great appreciation for the natural world – the human interrelationship with the natural world being, in itself, her sphere of spiritual communion. Then both my parents remarried. My father remarried a Jewish woman and my mom remarried a Muslim man. So that increased the religious diversity in our family quite radically.

JK: Was your stepmom practicing Judaism and your stepdad practicing Islam?

AT: Just a little. I wouldn’t want to say that they were not practicing. They were gently practicing. My stepmom, who was very much a second mom for me, not only did she have a Jewish background but she had a brother who was a “Jew Bu.” He officially became a Buddhist. So that was also part of my stepfamily.

JK: What form of Buddhism did he study?

AT: I’m not sure. Either Zen or … I’m pretty sure it wasn’t Tibetan or Chinese.

JK: It sounds like you grew up in a rich atmosphere that invited questioning.

AT: Yes. I think this was also part of the doubt. There were all these religious traditions, and I had lots of friends who invited me to various churches. I went now and then to different churches, although my parents were cautious about people’s attempts to convert their children. Going to Sunday school a few times with friends, I had questions. I was interested in asking them and in what was being taught. My home environment was one of free inquiry and open discussion in which questions were welcomed and encouraged.

The churches I visited with friends did not seem to be ones of free inquiry for children. That quite put me off. It seemed that there was more of an expectation to just believe what we were being told but not to think about it – even that it was wrong to think about it. Free inquiry was not encouraged. That seemed really strange to me, coming from my home environment. I learned to be leery of any circumstance where my own intelligence or inquiry was not respected. I was taught that this could be dangerous or harmful for people. My parents tried to inculcate in me a respectfulness with regards differing ways of doing things. They gave me the idea that most everyone will most likely think that they are right because they are doing the best they can, but that applying this as a judgment to others that one way, my way, is right and another wrong – is also something to look out for.

JK: You were taught to not traffic in views from early on.

AT: Maybe not 100 percent, but some part of it. My father had an interest in Taoism and Zen Buddhism, and later on in life, after my going forth into monastic life, he became much more active in pursuing that. Science seems to have been disappointing in some ways in terms of what he loved in scientific principle, like free inquiry into truthfulness and that kind of honesty. He started to look into Taoism and Zen Buddhism particularly in regards to those principles. For a while he self-identified as a Taoist.

JK: How do your parents feel about their daughter having become so fully involved in the Buddhist world?

AT: I think they, being compassionate people, felt quite a lot of sympathy for the painfulness of my own doubt and inquiry and my need to seek and search more deeply. I think they may have had appreciation and hope for me in what the Buddhist path might be able to offer. I think they may have had an interest in what could come out of that. Certainly a good number of my family members, in the times that I had to visit with them after my first five years away in Europe and Asia, really expressed quite a lot of interest, because for my family this was the stuff of movies and books and magazines. To have a family member go and do that was interesting to them.

JK: You’re living the adventure!

AT: Living the adventure! Yes. I certainly had a very strong adventuresome spirit, which I think was nurtured in my family environment, particularly by my father. The things he’s done in the form of social welfare, in that spirit of adventure, are quite an amazing example. And my mom mentioned to me, about ten years after I had entered monastic life, that she herself had also thought about becoming a nun when she was a younger person, a teenager. But she didn’t want to become a Catholic nun as things were, and she didn’t know what else she could do. She mentioned that at the time that she was pregnant with me she thought about that again. And then she realized that, being pregnant, “now my path is to be a mom.” She mentioned that while she was pregnant she was thinking about that. In a way, vicariously through her eldest daughter’s experience, she has shared together in parts of the experience of the monastic life.

JK: It’s so beautiful how the mother’s vision flowers in a world where there are more possibilities for her daughter.

AT: Yes. I wonder sometimes about karma and rebirth. Like the story of the Buddha’s own mom and how she changed, according to the story, in the time of her pregnancy and how important she was in terms of the Buddha’s choice for a mother. Now, through modern science, we see how the mother’s genetics can be modified by the baby. In a way, the baby influences the mother profoundly while the mother also influences the baby profoundly.

JK: I experienced that when I was pregnant. My daughter, Nicole, who has a very serene nature, influenced my feeling of serenity when I was pregnant with her and on meditation retreat.

Are we going to be perpetuating difficult and dysfunctional patterns, or are we going to get out of the loop with those things and become free and happy people?

AT: Yes, this is something I’ve wondered about. How much was that thinking of my mom’s coming from me, inside her, or how much did I get that from her? Because it can certainly go both ways. As you both change by the modification that’s happening between the two of you, it’s synergetic.

I’ve also learned from listening to my parents’ discussions about what it is to be a free person. They were in the universities in the 1960s. Questioning one’s parents, the ways of the parents, and going one’s own way was really an enormous culture and movement in those times. They talked a lot about these things when I was a young person. Over and over again they looked at the patterns they picked up from their parents and how difficult patterns are passed down from generation to generation. That’s something that they tried to bring a lot of mindfulness and awareness to and were trying to work with really, really strongly.

Because of hearing that so much as a young person, I developed a heightened awareness for this subject. I think that’s one of the things that made me not want to have children right off myself. There was a concern about passing on convoluted programs, or issues, from generation to generation. I wanted to have time to try and work those things out as best I could before passing them on to others.

You know, the idea that my aspiration to ordain may have come from my mom, from what I’ve learned in Buddhism, I feel so happy and amiable about that. What I learned from being a child born in the 1960s, that sets off these alarm bells. Those alarm bells are not outside the scope of the Buddha’s teachings. Really, at the heart of what’s there is the question: Are we going to be perpetuating difficult and dysfunctional patterns, or are we going to get out of the loop with those things and become free and happy people?

JK: What an interesting correlation – the Buddhist interest in freedom from patterns and the new psychological view of not wanting to pass negative patterns along to the next generation. I never put that together with the arahant path.

AT: To me that is right out front, very big!

JK: Who was your first Buddhist teacher?

Venerable Myeong Seong

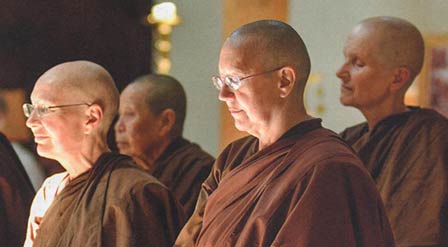

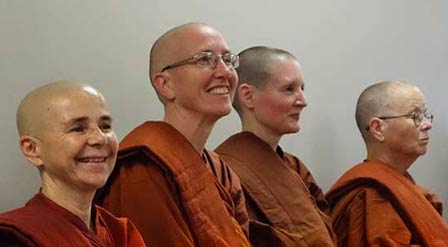

AT: As a younger person, when entering monastic life, I encountered a number of people who served as teachers. I think there wasn’t any one teacher, even when becoming an anagarika up through my first novice ordination. I never really thought that someone was truly my teacher until I met my venerable bhikkhuni mentor, the Venerable Myeong Seong, Bright Star. But she is not often called by her name but rather by her role.

JK: What was her position?

AT: She was the abbess and the main teacher of one of South Korea’s foremost bhikkhuni training monasteries. Later on she retired from being abbess and became the head of that monastery’s bhikkhuni council of elders, as well as the rector of its college of Buddhist studies. After that she was elected as the national head of the Korean Bhikkhuni Sangha, the female equivalent of what is called the supreme patriarch, like the supreme matriarch for the Bhikkhuni Sangha. But they don’t use those titles there. She may still have that position today.

JK: How did you come to her?

AT: I had heard about her through the Dharma bum circuit. At that time we weren’t using email or the web, and I was out and about internationally finding places of practice and teachers, going here and there. I heard that the situation for ordained women in Buddhism was best in Korea in terms of education, training, and support. The situation for bhikkhus and bhikkhunis was really quite equal in terms of these factors.

I remember traveling on a ferry and meeting with a fellow Dharma bum. He was just coming from South Korea, and he saw something there that he hadn’t seen in his experience of Buddhism anywhere. He was told there was a great Dharma master giving a talk at the main monastery of the Chogye Order in Seoul and that someone would be translating. He was invited to go, so he went. There were lots of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, and up on the high seat in that head monastery there was a bhikkhuni preaching, teaching them. In his travels he had never seen such a thing, a woman teacher at a main bhikkhu monastery being a primary, featured speaker. He was really impressed by that. He was raving about that when we were on that ferry together. I thought, “Oh, that’s interesting.”

When I went to South Korea later, I ended up going up to a hermitage in the Eight Peaks Mountains called Seong Jeon Am (Noble Sages Hermitage) and studying and practicing with a master who had been secluded there for about twenty-five years at that time. After being there for some time, I thought I would like to try to enter into the Bhikkhuni Sangha in South Korea.

JK: Were you inclined towards Theravada but studied in Mahayana because this was what was available?

AT: I had been in India, and the situation for women in monastic Theravada Buddhism at that time was largely nonexistent. For those who were lucky enough to receive samaneri ordination and encouraged to live and practice like a bhikkhuni, especially for Westerners, as was the case also with Tibetan Buddhism, we were expected to take care of and support ourselves. As a young person in my early twenties, I had given up everything, left everything behind when I became an anagarika. To support myself was not so easy, as was also the case with others. What was often expected from Westerners was to be giving support. There is the thought that the U.S. and Europe are rich countries and the Asian countries are poorer and in need of support in many places.

This was not always the case with men. I heard someone say—it’s kind of a crass comment—“If you were a man, you could just plug into the system in Thailand and you’d be fully supported. There are lots of great teachers there. It’s like Buddhist heaven.” I thought, “You’re right, that would be good.” But, being a woman, if I were to go, I would have to think about arranging for my own support. You pay and go for some time on retreat. When the money runs out, then you leave, go to work, make some money, then go back on retreat again. This is what a lot of women have done, and what a lot of women are still doing.

For someone who has left everything and doesn’t want to go back—in my heart I didn’t even feel able to go back—it seemed like where I wanted to go was much deeper into this path, not coming out for a while and then back in. I was really looking for how I could do that. What was asked of me as a very young and newly robed person in terms of supporting myself seemed pretty difficult. It seemed like the act of trying to support myself and trying to seek some gainful employment didn’t serve what my heart’s desire was. Hearing that there were places where women could go and really be received into the Sangha and fully trained and supported seemed like the direction I needed to go. I started looking for where that might be possible. What I heard was, “Go north,” which meant Taiwan and South Korea. At that time Buddhism had not come back big in China.

So I went north. When I went to Taiwan, I found monastics practicing a lot of repentance. A lot of recitation of the names of buddhas and bodhisattvas, a strong emphasis on vegetarianism, on childhood education, and on education in general. The main practices of recollection of the Buddha’s name and repentance did not appeal to me deeply as my way of practice. In South Korea I found something that was really important to me, and that was the San Lim Seon Jeong, the Mountain Forest Meditation Tradition. It was completely and fully open to women. The stark, rugged simplicity of this tradition and the time in meditative inquiry—these things really struck a chord with me. I resonated with the part of learning from nature and the part about inquiry, working with radical inquiry. From young in life, as you heard, these had been things that really struck a strong chord in me.

JK: What sort of inquiry practice did you work with?

AT: My venerable bhikkhuni mentor did not actually practice inquiry meditation. She was very strong in Dhamma teaching. She did excellent work in terms of the Bhikkhuni Sangha and developing a training monastery and assistance for a training monastery. Her love and her heart is in Dhamma study and Dhamma teaching. So my own venerable bhikkhuni mentor did not teach me direct meditative inquiry, although I felt very intuitively connected to her when first meeting her. I bowed down to her nine times, not knowing why I did it. She recognized nine bows, from some teachings, as my asking her to be my teacher. She asked, “Do you want me to be your teacher?” I thought about it and from a deep intuition answered yes, almost as a surprise to myself. Despite this deep connection, due to my love for meditative inquiry, she sent me to study and train with another bhikkhuni who is kind of a Dhamma relative of hers who had studied a type of inquiry meditation that in Korean is called hwadu meditation and in Chinese Chan Buddhism is called the hua tou.

JK: Who was this teacher?

AT: The teacher is the Elder Kyeong Hi Sunim. I was sent by my teacher to serve as personal attendant to her and thus be able to learn from her closely. That was a normal thing in the Bhikkhuni Sangha, to send a student to an associated bhikkhuni teacher whom she might be able to learn from. It’s the same in the Thai Bhikkhu Sangha. You may have heard stories about Ajahn Chah sending his students to a related teacher whom he thought they would learn something of benefit from. So I had the opportunity to study with her as well as a number of the other teachers of the hwadu meditation practice. I was learning about practices and teachings, trying to seek out the heart of the Buddhist path via meditation and Dharma understanding.

JK: What was the hwadu practice? Is that an inquiry practice like koans?

AT: It’s not working with koans but with the heart or essence of the koan. The koan would be the story or the case of an awakening, and the hwadu literally means the “head of the word,” like the fountainhead of this streaming Dhamma, it is the source.

I know that there hasn’t been so much written or so much taught about the hwadu practice in the West. In fact, for those who do this practice, to find anyone else to talk with about the practice is rare. I think the late Father Thomas Hand, a partner in monastic interreligious dialogue, was the only one I ever met. He was a Jesuit priest and had learned the hua tou practice in Japan and had practiced with it deeply as a Christian. He didn’t find it at variance in any way with the essential heart of his Jesuit practice. I learned from him about this in a monastic interreligious dialogue gathering called “Bodhisattva Path/Christ Path.” But he was the first and only person in the United States whom I talked to who really worked deeply with that practice (at least as I had learned it) and could speak about it fluently in English. I haven’t ever seen anything published about it that seemed accessible or mainstream. It’s not well known.

JK: Is it done in conjunction with deep meditation practice?

AT: Yes.

JK: Is it a practice that you bring into retreat?

AT: Yes, and it’s a whole life practice. In working with it, you are encouraged to start with the first moment of consciousness upon waking in the morning, then develop working with the practice with every activity of daily life. It doesn’t exclude deep retreat practice. It is a kind of essential practice that is, by nature, before words and hard to put into words, but known within one’s heart when it’s touched upon.

JK: So you did this practice in Korea. Practicing in this Mahayana country, did you have more of an inclination toward the bodhisattva or arahant path, or did the question even come up?

I heard a saying by Ajahn Chah that I liked very much. When he was asked about being a bodhisattva or being an arahant he said, “Don’t try to be anything at all.”

AT: It wasn’t something that mattered so much to me. I knew that there was a lot of concern about that. I developed an appreciation for whoever has the interest and willingness out of compassion to be available, to be born. It’s kind of amazing to think of one who is willing to be born again and again for the welfare of others. There’s all this talk about bodhisattvas and arahants and making distinctions between Theravada and Mahayana. I felt a bit of angst about the way some people approached that subject. I heard a saying by Ajahn Chah that I liked very much. When he was asked about being a bodhisattva or being an arahant he said, “Don’t try to be anything at all.” I appreciated that.

I have a strong appreciation for the core of these matters. To me, that gets down to what’s important and what I feel is deeply important on the path.

JK: What would you say is the tradition you teach? Is it a universalist Buddhism, or is there a lineage that you feel is your lineage?

AT: I’m pretty clear that at this time I teach and study in Theravada Buddhism. That is, to my mind, the heart or the essence of the Buddha’s teachings. There are all kinds of things in Theravada Buddhism—many cultural aspects and developed traditions and commentaries and ethnic traditions. I’m not trying to do all of that, and I don’t think there is any way someone could do all of that. I’m interested in the essential practices of what the Buddha taught.

JK: What is it about Buddhism that speaks directly to your heart?

AT: It’s what I find in the Four Noble Truths—about suffering and the end of suffering. Also, about there being a practical path, a way to end suffering. I’m interested in the Ovada Patimokkha, the Buddha’s first teaching, which is first about reducing and ending suffering, both my own personal difficulty and that of others as well. The Buddha’s teachings may match any circumstances, that is, be appropriately applied to any given situation in which there is suffering or “dis-ease” for their alleviation and cure. Second is what makes us happy, the things that not only make for our short-term well-being but that lead to deepening, expanding, and establishing real long-term happiness, peace, and freedom.

The third point of the Ovada Patimokkha goes back to path again, the path of purifying one’s mind and heart. Being able to do that is essential for understanding what does work and what doesn’t work-and also for strengthening the mind and creating the context in which the work can be done. Once you see what needs to be done, you still need to have the strength, the resource, the container for doing that. The purification, the clarification of the heart, is that.

In Zen the last point of these three is different, but in Theravada the last point is purifying the mind. Not to say the people in Zen aren’t doing that, not at all. If they are practicing rightly, they are. In a way it’s a technical distinction, for if we do that, it naturally benefits all living beings.

JK: That is so beautiful, Ayya. Before we close I wanted to say that I met your bhikkhuni mentor when I was in Thailand for the Outstanding Women in Buddhism awards and spent some time with her. The thrust of the conversation was about how can we support the Thai Bhikkhuni Sangha. Your teacher was strong on wanting to support Thai women.

AT: She’s done so much for them. She very much encouraged me and blessed me to go forth and do what I could.

JK: And look what you’ve done! That’s exactly what you’ve done.

AT: She had been trying and trying in years past and hadn’t made much headway. She thought that perhaps someone not quite so high up might be able to do more. She gave me her blessing and encouragement to do that.

JK: Having seen her and met her, and knowing the skills and practices you were given…

AT: She was aware of this and very much wanted me to have those skills. She was aware that I was already in another tradition before coming to her but wanted me to go through the Korean Buddhist training from the beginning to get the entirety of it, all of the benefit and experience out of that. She said that explicitly. She really wanted that because she thought that it was important to have that experience, not only for myself, my own strengthening and fullness of my own monastic life, but to be able to rightly pass that on to others. She mentioned that explicitly. That’s one of the things that is great about her. With regards to community, she has big view in terms of causality and causation. Her Dhamma about these kinds of things is very right. Not only is it big, but it comes down to individual circumstances and timeliness.

JK: This is amazing. She sent her beloved daughter out to widen the circle. I have a deep feeling for that because I’ve seen her and know her character. She is like a mountain. We spent five days in a funky bus together with her, Dr. Lee, and some others. Dr. Lee took us around to different sites in Thailand. I really appreciate her strength.

AT: She was deliberately trained in that. The monastery I trained at, my home monastery, which she was abbess of, is in the Leaping Tiger Mountain Wilderness of Korea’s Kyeong Sang Buk Do province. There were no more tigers in the mountains, but it was said that in the monastery one tigress remains, and she is it. Being a tigress in the mountains is her realm and her domain.

JK: What a great gift she gave us. Thank you for sharing the early years of your path with me. I hope we can talk soon about your journey back to the West.

About the Author

Jacqueline Kramer, author of Buddha Mom – the Path of Mindful Mothering, has been studying and practicing Buddhism for over 36 years. Her root teachings are in the Sri Lankan Theravadin tradition and she is now studying Zen koans. She is the director of Hearth Foundation which offers classes and support for parents who wish to awaken at home. The website is www.hearth-foundation.org

For the last few years, she has been focusing on painting and has created a Syrian refugee art project which helps to create fundraisers for the Syrian refugees through the International Rescue Committee. See her work at http://jacquelinekramer.work/

From the August 2012 edition of Present

I first met Ayya Tathaaloka when she was in Northern California looking over the land near Jenner that was to become the Aranya Bodhi Forest Hermitage. I had an immediate feeling of sisterhood with Ayya. It turns out that both of us were deeply influenced by her bhikkhuni mentor, the Venerable Myeong Seong of south Korea. The venerable was dedicated to helping rebuild the Bhikkhuni Sangha, and that intention was transmitted to both of us at different times in different ways. Ayya Tathaaloka has bravely and intelligently gone about supporting the growth of the Bhikkhuni Sangha by helping establish the first bhikkhuni forest hermitage in the West, by acting as a preceptor for many Western bhikkhunis, and in many other large and small ways. She has taken great pains to insure recognition of the Bhikkhuni Sangha by careful scholarship and adherence to established procedures.

We spoke again on a sunny May afternoon in 2012, exploring how her early life brought her to the gates of the Bhikkhuni Sangha. The question of how our Western Buddhist pioneers came to the path is an intriguing one. What makes a child from a JudeoChristian culture seek out Buddhism? What sorts of influences and personality traits draw a child to the East? It’s no surprise that an adventuresome, independent spirit and a questioning mind are necessary for the journey. A certain amount of doubt and discomfort are also important catalysts. In this interview we get a glimpse of Ayya Tathaaloka’s adventuresome, independent spirit; her early doubt; and the kind influences that guided her East to Buddhism.

Jacqueline Kramer: What was your first glimmer of Buddhism?

Ayya Tathaaloka: This is a question that other people are able to answer, but I find for myself that I can’t. I don’t remember my first encounter with Buddhism. Growing up, there were books that had things about Buddhism around me. There was also Buddhism in the movies and on TV and magazines like National Geographic. I remember seeing robed Buddhist monks in jungle environments. There are some things I remember from my teenage times that particularly impressed me. Whether you’d say they are connected to Buddhism or not, I’m not sure. I watched the show Kung Fu. David Carradine was playing a man who was a Buddhist novice training with a master and was wandering from place to place in the old Wild West learning various life lessons.

Ayya Tathaaloka: This is a question that other people are able to answer, but I find for myself that I can’t. I don’t remember my first encounter with Buddhism. Growing up, there were books that had things about Buddhism around me. There was also Buddhism in the movies and on TV and magazines like National Geographic. I remember seeing robed Buddhist monks in jungle environments. There are some things I remember from my teenage times that particularly impressed me. Whether you’d say they are connected to Buddhism or not, I’m not sure. I watched the show Kung Fu. David Carradine was playing a man who was a Buddhist novice training with a master and was wandering from place to place in the old Wild West learning various life lessons.

I was discouraged when I asked whether women could ordain and was told that this was a possibility open only for men. To my young teenager’s sense, not knowing much, that seemed very strange to me. That series became a kind of paradigm for me. I understood the pattern that you pick up wisdom from teachers or teachings and then in life circumstances, you reflect on that wisdom and apply that to the circumstances that you’re meeting in life. Then the circumstances themselves have the opportunity for growth or catharsis or reflection. They may become part of your ongoing awakening experience. Those teachings then become relevant, come to life, and become manifest. That’s something that I got from watching that show.

Of course, that’s not the only place I saw that paradigm; it was all around. There was encouragement from my parents to learn and apply what has been learned to life circumstances. So that’s not a new thing, but that show illustrated these lessons and their wisdom in a classical Buddhist context.

The Lord of the Rings and Star Wars also contained deliberate use of archetypical images of Christian and Buddhist monastics, paradigms of forces of good and evil, wise mentors, and the development and cultivation of the acolyte. The disciples were tried and tested, and triumphing over the forces inside themselves was the big issue. The small person who is from nowhere is the one who then triumphs and saves the world. They were archetypes of spiritual seekers.

Also, there were a couple of other things. I remember one friend of the family had gone to Thailand with the Peace Corps. He ordained for three months as a Buddhist monk during the vassa after finishing his assignment. I remember hearing about that experience and finding it very interesting hearing about what it was like and learning that it was possible for a Western person to go and do that. This friend was male and I was interested in whether this would be a possibility for myself or not. It sounded like a really great learning experience. I was looking at my possibilities for higher education at that time. To have that kind of training in sila (virtue) and meditation and wisdom seemed interesting and excellent as compared to university options.

I was discouraged when I asked whether women could do that too and was told that this was a possibility open only for men.

But I was discouraged when I asked whether women could do that too and was told that this was a possibility open only for men. I remember thinking that I had seen some old Buddhist texts and had the idea that women had been ordained in Buddhism in the Buddha’s lifetime. I felt that if the Buddha was truly enlightened, this possibility should be open for women as well. I felt it should be there and that it had been there. It seemed really strange to me that this would not be so in a place where Buddhism was thriving, in an affirmatively Buddhist country. To my young teenager’s sense, not knowing much, that seemed very strange to me.

Not so long after that another family friend who came by to visit had been at Shasta Abbey. I hadn’t heard of Shasta Abbey before. I was living in Washington State and at that time we didn’t have any Buddhist temples or monasteries around that part of the country. But Mt. Shasta was just south of us, not so very far. That friend mentioned that there were both male and female Buddhist monks there. When I heard that, I thought, “Right! That’s how it should be.” I felt this kind of awakening interest then. And I learned there were these differing dynamics about ordination and women being able to ordain or not.

I would say another memorable thing would be a little bit later, still as a teenager, encountering two books that were quite important. One was Master Sheng Yen’s Faith in Mind. It is an English translation of an enlightenment poem by the Third Zen Patriarch in China. I ended up studying and practicing the hua tou with him later.

Doubt can become a hindrance and cause a lot of suffering in our minds. For me, this accumulated doubt was an abiding, underlying pit of suffering.

JK: Where was he?

AT: He was in Taiwan. He also founded the Dharma Drum Buddhist Association Center on the East Coast here in the U.S., and it has a West Coast branch as well. That poem by this old Buddhist master touched me.

Then there was the Blue Cliff Records, the koans. Someone introduced that book to me as a book of Buddhist wisdom because I seemed to be interested in such. I opened it up and began to look at it, and it brought up tremendous doubt in me right away – the underlying doubt about the many things in life and in our world that were always simmering below the surface. We’re skimming on top of that in ordinary life.

JK: Was this like the great doubt that Zen teachers speak of, or was this doubt as in a hindrance?

AT: I think this would be the great doubt that the Zen teachers talk about – deep and fundamental doubt. Touching into and penetrating this is the clearing of a hindrance.

JK: Like what are we doing here?

AT: Yes. Of course, before one has a breakthrough to the great inquiry – what are we doing here? – that and the kind of doubt that is a hindrance in people’s ordinary lives, dance intertwined, intermingled with each other. This is because of not applying that doubt to inquiry in wise ways. When that’s so, doubt can become a hindrance and cause a lot of suffering in our minds. For me, this accumulated doubt was an abiding, underlying pit of suffering. Reading even a few of the koan cases drew it all together into a great mass – like I was a cat that needed to vomit up a fur ball as big as the whole world. This was a great mental energetic mass of everything I had been unable to digest in the whole world because of not having right understanding. At that time, I didn’t know how to see it correctly and penetrate that great mass.

Thinking back I would say those were impressive things, but I don’t remember what the first thing was early on. I know both my mother and my father seemed to have respect for the Buddha.

JK: What religion did you grow up with?

AT: I didn’t grow up with one particular religion. My father was an atheist scientist and his family was not religious. They were a family of engineers, with a lawyer or two. They were into the material world and big into cause-and-effect forensic science, which is an investigative science. I got a kind of religion of science and investigation from them. My mom had a partly Episcopalian background with a large dose of naturalism – love for the natural world. She had studied botany, worked as a naturalist, and ended up doing her Ph.D. in phenomenology, which originated with that name under the German philosopher Heidegger, who studied Yogacara Buddhism, which is also known as Vijñanavada, Cittamatra, or the Mind-Only School of Buddhism. From her I got a great appreciation for the natural world – the human interrelationship with the natural world being, in itself, her sphere of spiritual communion. Then both my parents remarried. My father remarried a Jewish woman and my mom remarried a Muslim man. So that increased the religious diversity in our family quite radically.

AT: I didn’t grow up with one particular religion. My father was an atheist scientist and his family was not religious. They were a family of engineers, with a lawyer or two. They were into the material world and big into cause-and-effect forensic science, which is an investigative science. I got a kind of religion of science and investigation from them. My mom had a partly Episcopalian background with a large dose of naturalism – love for the natural world. She had studied botany, worked as a naturalist, and ended up doing her Ph.D. in phenomenology, which originated with that name under the German philosopher Heidegger, who studied Yogacara Buddhism, which is also known as Vijñanavada, Cittamatra, or the Mind-Only School of Buddhism. From her I got a great appreciation for the natural world – the human interrelationship with the natural world being, in itself, her sphere of spiritual communion. Then both my parents remarried. My father remarried a Jewish woman and my mom remarried a Muslim man. So that increased the religious diversity in our family quite radically.

JK: Was your stepmom practicing Judaism and your stepdad practicing Islam?

AT: Just a little. I wouldn’t want to say that they were not practicing. They were gently practicing. My stepmom, who was very much a second mom for me, not only did she have a Jewish background but she had a brother who was a “Jew Bu.” He officially became a Buddhist. So that was also part of my stepfamily.

JK: What form of Buddhism did he study?

AT: I’m not sure. Either Zen or … I’m pretty sure it wasn’t Tibetan or Chinese.

JK: It sounds like you grew up in a rich atmosphere that invited questioning.

AT: Yes. I think this was also part of the doubt. There were all these religious traditions, and I had lots of friends who invited me to various churches. I went now and then to different churches, although my parents were cautious about people’s attempts to convert their children. Going to Sunday school a few times with friends, I had questions. I was interested in asking them and in what was being taught. My home environment was one of free inquiry and open discussion in which questions were welcomed and encouraged.

The churches I visited with friends did not seem to be ones of free inquiry for children. That quite put me off. It seemed that there was more of an expectation to just believe what we were being told but not to think about it – even that it was wrong to think about it. Free inquiry was not encouraged. That seemed really strange to me, coming from my home environment. I learned to be leery of any circumstance where my own intelligence or inquiry was not respected. I was taught that this could be dangerous or harmful for people. My parents tried to inculcate in me a respectfulness with regards differing ways of doing things. They gave me the idea that most everyone will most likely think that they are right because they are doing the best they can, but that applying this as a judgment to others that one way, my way, is right and another wrong – is also something to look out for.

JK: You were taught to not traffic in views from early on.

AT: Maybe not 100 percent, but some part of it. My father had an interest in Taoism and Zen Buddhism, and later on in life, after my going forth into monastic life, he became much more active in pursuing that. Science seems to have been disappointing in some ways in terms of what he loved in scientific principle, like free inquiry into truthfulness and that kind of honesty. He started to look into Taoism and Zen Buddhism particularly in regards to those principles. For a while he self-identified as a Taoist.

JK: How do your parents feel about their daughter having become so fully involved in the Buddhist world?

AT: I think they, being compassionate people, felt quite a lot of sympathy for the painfulness of my own doubt and inquiry and my need to seek and search more deeply. I think they may have had appreciation and hope for me in what the Buddhist path might be able to offer. I think they may have had an interest in what could come out of that. Certainly a good number of my family members, in the times that I had to visit with them after my first five years away in Europe and Asia, really expressed quite a lot of interest, because for my family this was the stuff of movies and books and magazines. To have a family member go and do that was interesting to them.

JK: You’re living the adventure!

AT: Living the adventure! Yes. I certainly had a very strong adventuresome spirit, which I think was nurtured in my family environment, particularly by my father. The things he’s done in the form of social welfare, in that spirit of adventure, are quite an amazing example. And my mom mentioned to me, about ten years after I had entered monastic life, that she herself had also thought about becoming a nun when she was a younger person, a teenager. But she didn’t want to become a Catholic nun as things were, and she didn’t know what else she could do. She mentioned that at the time that she was pregnant with me she thought about that again. And then she realized that, being pregnant, “now my path is to be a mom.” She mentioned that while she was pregnant she was thinking about that. In a way, vicariously through her eldest daughter’s experience, she has shared together in parts of the experience of the monastic life.

JK: It’s so beautiful how the mother’s vision flowers in a world where there are more possibilities for her daughter.

AT: Yes. I wonder sometimes about karma and rebirth. Like the story of the Buddha’s own mom and how she changed, according to the story, in the time of her pregnancy and how important she was in terms of the Buddha’s choice for a mother. Now, through modern science, we see how the mother’s genetics can be modified by the baby. In a way, the baby influences the mother profoundly while the mother also influences the baby profoundly.

JK: I experienced that when I was pregnant. My daughter, Nicole, who has a very serene nature, influenced my feeling of serenity when I was pregnant with her and on meditation retreat.

Are we going to be perpetuating difficult and dysfunctional patterns, or are we going to get out of the loop with those things and become free and happy people?

AT: Yes, this is something I’ve wondered about. How much was that thinking of my mom’s coming from me, inside her, or how much did I get that from her? Because it can certainly go both ways. As you both change by the modification that’s happening between the two of you, it’s synergetic.

I’ve also learned from listening to my parents’ discussions about what it is to be a free person. They were in the universities in the 1960s. Questioning one’s parents, the ways of the parents, and going one’s own way was really an enormous culture and movement in those times. They talked a lot about these things when I was a young person. Over and over again they looked at the patterns they picked up from their parents and how difficult patterns are passed down from generation to generation. That’s something that they tried to bring a lot of mindfulness and awareness to and were trying to work with really, really strongly.

Because of hearing that so much as a young person, I developed a heightened awareness for this subject. I think that’s one of the things that made me not want to have children right off myself. There was a concern about passing on convoluted programs, or issues, from generation to generation. I wanted to have time to try and work those things out as best I could before passing them on to others.

You know, the idea that my aspiration to ordain may have come from my mom, from what I’ve learned in Buddhism, I feel so happy and amiable about that. What I learned from being a child born in the 1960s, that sets off these alarm bells. Those alarm bells are not outside the scope of the Buddha’s teachings. Really, at the heart of what’s there is the question: Are we going to be perpetuating difficult and dysfunctional patterns, or are we going to get out of the loop with those things and become free and happy people?

JK: What an interesting correlation – the Buddhist interest in freedom from patterns and the new psychological view of not wanting to pass negative patterns along to the next generation. I never put that together with the arahant path.

AT: To me that is right out front, very big!

JK: Who was your first Buddhist teacher?

Venerable Myeong Seong

AT: As a younger person, when entering monastic life, I encountered a number of people who served as teachers. I think there wasn’t any one teacher, even when becoming an anagarika up through my first novice ordination. I never really thought that someone was truly my teacher until I met my venerable bhikkhuni mentor, the Venerable Myeong Seong, Bright Star. But she is not often called by her name but rather by her role.

JK: What was her position?

AT: She was the abbess and the main teacher of one of South Korea’s foremost bhikkhuni training monasteries. Later on she retired from being abbess and became the head of that monastery’s bhikkhuni council of elders, as well as the rector of its college of Buddhist studies. After that she was elected as the national head of the Korean Bhikkhuni Sangha, the female equivalent of what is called the supreme patriarch, like the supreme matriarch for the Bhikkhuni Sangha. But they don’t use those titles there. She may still have that position today.

JK: How did you come to her?

AT: I had heard about her through the Dharma bum circuit. At that time we weren’t using email or the web, and I was out and about internationally finding places of practice and teachers, going here and there. I heard that the situation for ordained women in Buddhism was best in Korea in terms of education, training, and support. The situation for bhikkhus and bhikkhunis was really quite equal in terms of these factors.

I remember traveling on a ferry and meeting with a fellow Dharma bum. He was just coming from South Korea, and he saw something there that he hadn’t seen in his experience of Buddhism anywhere. He was told there was a great Dharma master giving a talk at the main monastery of the Chogye Order in Seoul and that someone would be translating. He was invited to go, so he went. There were lots of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, and up on the high seat in that head monastery there was a bhikkhuni preaching, teaching them. In his travels he had never seen such a thing, a woman teacher at a main bhikkhu monastery being a primary, featured speaker. He was really impressed by that. He was raving about that when we were on that ferry together. I thought, “Oh, that’s interesting.”

When I went to South Korea later, I ended up going up to a hermitage in the Eight Peaks Mountains called Seong Jeon Am (Noble Sages Hermitage) and studying and practicing with a master who had been secluded there for about twenty-five years at that time. After being there for some time, I thought I would like to try to enter into the Bhikkhuni Sangha in South Korea.

JK: Were you inclined towards Theravada but studied in Mahayana because this was what was available?

AT: I had been in India, and the situation for women in monastic Theravada Buddhism at that time was largely nonexistent. For those who were lucky enough to receive samaneri ordination and encouraged to live and practice like a bhikkhuni, especially for Westerners, as was the case also with Tibetan Buddhism, we were expected to take care of and support ourselves. As a young person in my early twenties, I had given up everything, left everything behind when I became an anagarika. To support myself was not so easy, as was also the case with others. What was often expected from Westerners was to be giving support. There is the thought that the U.S. and Europe are rich countries and the Asian countries are poorer and in need of support in many places.

This was not always the case with men. I heard someone say—it’s kind of a crass comment—“If you were a man, you could just plug into the system in Thailand and you’d be fully supported. There are lots of great teachers there. It’s like Buddhist heaven.” I thought, “You’re right, that would be good.” But, being a woman, if I were to go, I would have to think about arranging for my own support. You pay and go for some time on retreat. When the money runs out, then you leave, go to work, make some money, then go back on retreat again. This is what a lot of women have done, and what a lot of women are still doing.

For someone who has left everything and doesn’t want to go back—in my heart I didn’t even feel able to go back—it seemed like where I wanted to go was much deeper into this path, not coming out for a while and then back in. I was really looking for how I could do that. What was asked of me as a very young and newly robed person in terms of supporting myself seemed pretty difficult. It seemed like the act of trying to support myself and trying to seek some gainful employment didn’t serve what my heart’s desire was. Hearing that there were places where women could go and really be received into the Sangha and fully trained and supported seemed like the direction I needed to go. I started looking for where that might be possible. What I heard was, “Go north,” which meant Taiwan and South Korea. At that time Buddhism had not come back big in China.

So I went north. When I went to Taiwan, I found monastics practicing a lot of repentance. A lot of recitation of the names of buddhas and bodhisattvas, a strong emphasis on vegetarianism, on childhood education, and on education in general. The main practices of recollection of the Buddha’s name and repentance did not appeal to me deeply as my way of practice. In South Korea I found something that was really important to me, and that was the San Lim Seon Jeong, the Mountain Forest Meditation Tradition. It was completely and fully open to women. The stark, rugged simplicity of this tradition and the time in meditative inquiry—these things really struck a chord with me. I resonated with the part of learning from nature and the part about inquiry, working with radical inquiry. From young in life, as you heard, these had been things that really struck a strong chord in me.

JK: What sort of inquiry practice did you work with?

AT: My venerable bhikkhuni mentor did not actually practice inquiry meditation. She was very strong in Dhamma teaching. She did excellent work in terms of the Bhikkhuni Sangha and developing a training monastery and assistance for a training monastery. Her love and her heart is in Dhamma study and Dhamma teaching. So my own venerable bhikkhuni mentor did not teach me direct meditative inquiry, although I felt very intuitively connected to her when first meeting her. I bowed down to her nine times, not knowing why I did it. She recognized nine bows, from some teachings, as my asking her to be my teacher. She asked, “Do you want me to be your teacher?” I thought about it and from a deep intuition answered yes, almost as a surprise to myself. Despite this deep connection, due to my love for meditative inquiry, she sent me to study and train with another bhikkhuni who is kind of a Dhamma relative of hers who had studied a type of inquiry meditation that in Korean is called hwadu meditation and in Chinese Chan Buddhism is called the hua tou.

JK: Who was this teacher?

AT: The teacher is the Elder Kyeong Hi Sunim. I was sent by my teacher to serve as personal attendant to her and thus be able to learn from her closely. That was a normal thing in the Bhikkhuni Sangha, to send a student to an associated bhikkhuni teacher whom she might be able to learn from. It’s the same in the Thai Bhikkhu Sangha. You may have heard stories about Ajahn Chah sending his students to a related teacher whom he thought they would learn something of benefit from. So I had the opportunity to study with her as well as a number of the other teachers of the hwadu meditation practice. I was learning about practices and teachings, trying to seek out the heart of the Buddhist path via meditation and Dharma understanding.

JK: What was the hwadu practice? Is that an inquiry practice like koans?

AT: It’s not working with koans but with the heart or essence of the koan. The koan would be the story or the case of an awakening, and the hwadu literally means the “head of the word,” like the fountainhead of this streaming Dhamma, it is the source.

I know that there hasn’t been so much written or so much taught about the hwadu practice in the West. In fact, for those who do this practice, to find anyone else to talk with about the practice is rare. I think the late Father Thomas Hand, a partner in monastic interreligious dialogue, was the only one I ever met. He was a Jesuit priest and had learned the hua tou practice in Japan and had practiced with it deeply as a Christian. He didn’t find it at variance in any way with the essential heart of his Jesuit practice. I learned from him about this in a monastic interreligious dialogue gathering called “Bodhisattva Path/Christ Path.” But he was the first and only person in the United States whom I talked to who really worked deeply with that practice (at least as I had learned it) and could speak about it fluently in English. I haven’t ever seen anything published about it that seemed accessible or mainstream. It’s not well known.

JK: Is it done in conjunction with deep meditation practice?

AT: Yes.

JK: Is it a practice that you bring into retreat?

AT: Yes, and it’s a whole life practice. In working with it, you are encouraged to start with the first moment of consciousness upon waking in the morning, then develop working with the practice with every activity of daily life. It doesn’t exclude deep retreat practice. It is a kind of essential practice that is, by nature, before words and hard to put into words, but known within one’s heart when it’s touched upon.

JK: So you did this practice in Korea. Practicing in this Mahayana country, did you have more of an inclination toward the bodhisattva or arahant path, or did the question even come up?

I heard a saying by Ajahn Chah that I liked very much. When he was asked about being a bodhisattva or being an arahant he said, “Don’t try to be anything at all.”

AT: It wasn’t something that mattered so much to me. I knew that there was a lot of concern about that. I developed an appreciation for whoever has the interest and willingness out of compassion to be available, to be born. It’s kind of amazing to think of one who is willing to be born again and again for the welfare of others. There’s all this talk about bodhisattvas and arahants and making distinctions between Theravada and Mahayana. I felt a bit of angst about the way some people approached that subject. I heard a saying by Ajahn Chah that I liked very much. When he was asked about being a bodhisattva or being an arahant he said, “Don’t try to be anything at all.” I appreciated that.

I have a strong appreciation for the core of these matters. To me, that gets down to what’s important and what I feel is deeply important on the path.

JK: What would you say is the tradition you teach? Is it a universalist Buddhism, or is there a lineage that you feel is your lineage?

AT: I’m pretty clear that at this time I teach and study in Theravada Buddhism. That is, to my mind, the heart or the essence of the Buddha’s teachings. There are all kinds of things in Theravada Buddhism—many cultural aspects and developed traditions and commentaries and ethnic traditions. I’m not trying to do all of that, and I don’t think there is any way someone could do all of that. I’m interested in the essential practices of what the Buddha taught.

JK: What is it about Buddhism that speaks directly to your heart?

AT: It’s what I find in the Four Noble Truths—about suffering and the end of suffering. Also, about there being a practical path, a way to end suffering. I’m interested in the Ovada Patimokkha, the Buddha’s first teaching, which is first about reducing and ending suffering, both my own personal difficulty and that of others as well. The Buddha’s teachings may match any circumstances, that is, be appropriately applied to any given situation in which there is suffering or “dis-ease” for their alleviation and cure. Second is what makes us happy, the things that not only make for our short-term well-being but that lead to deepening, expanding, and establishing real long-term happiness, peace, and freedom.

The third point of the Ovada Patimokkha goes back to path again, the path of purifying one’s mind and heart. Being able to do that is essential for understanding what does work and what doesn’t work-and also for strengthening the mind and creating the context in which the work can be done. Once you see what needs to be done, you still need to have the strength, the resource, the container for doing that. The purification, the clarification of the heart, is that.

In Zen the last point of these three is different, but in Theravada the last point is purifying the mind. Not to say the people in Zen aren’t doing that, not at all. If they are practicing rightly, they are. In a way it’s a technical distinction, for if we do that, it naturally benefits all living beings.

JK: That is so beautiful, Ayya. Before we close I wanted to say that I met your bhikkhuni mentor when I was in Thailand for the Outstanding Women in Buddhism awards and spent some time with her. The thrust of the conversation was about how can we support the Thai Bhikkhuni Sangha. Your teacher was strong on wanting to support Thai women.

AT: She’s done so much for them. She very much encouraged me and blessed me to go forth and do what I could.

JK: And look what you’ve done! That’s exactly what you’ve done.

AT: She had been trying and trying in years past and hadn’t made much headway. She thought that perhaps someone not quite so high up might be able to do more. She gave me her blessing and encouragement to do that.

JK: Having seen her and met her, and knowing the skills and practices you were given…

AT: She was aware of this and very much wanted me to have those skills. She was aware that I was already in another tradition before coming to her but wanted me to go through the Korean Buddhist training from the beginning to get the entirety of it, all of the benefit and experience out of that. She said that explicitly. She really wanted that because she thought that it was important to have that experience, not only for myself, my own strengthening and fullness of my own monastic life, but to be able to rightly pass that on to others. She mentioned that explicitly. That’s one of the things that is great about her. With regards to community, she has big view in terms of causality and causation. Her Dhamma about these kinds of things is very right. Not only is it big, but it comes down to individual circumstances and timeliness.

JK: This is amazing. She sent her beloved daughter out to widen the circle. I have a deep feeling for that because I’ve seen her and know her character. She is like a mountain. We spent five days in a funky bus together with her, Dr. Lee, and some others. Dr. Lee took us around to different sites in Thailand. I really appreciate her strength.

AT: She was deliberately trained in that. The monastery I trained at, my home monastery, which she was abbess of, is in the Leaping Tiger Mountain Wilderness of Korea’s Kyeong Sang Buk Do province. There were no more tigers in the mountains, but it was said that in the monastery one tigress remains, and she is it. Being a tigress in the mountains is her realm and her domain.

JK: What a great gift she gave us. Thank you for sharing the early years of your path with me. I hope we can talk soon about your journey back to the West.

About the Author

Jacqueline Kramer, author of Buddha Mom – the Path of Mindful Mothering, has been studying and practicing Buddhism for over 36 years. Her root teachings are in the Sri Lankan Theravadin tradition and she is now studying Zen koans. She is the director of Hearth Foundation which offers classes and support for parents who wish to awaken at home. The website is www.hearth-foundation.org

For the last few years, she has been focusing on painting and has created a Syrian refugee art project which helps to create fundraisers for the Syrian refugees through the International Rescue Committee. See her work at http://jacquelinekramer.work/