What Buddhism Gave Me

by Munissara Bhikkhuni

What Buddhism Gave Me

by Munissara Bhikkhuni

From the December 2012 edition of Present

My passport says I am Thai, but actually I have lived most of my life outside of predominantly-Buddhist Thailand. Although my contact with Buddhist-y things growing up was thus quite limited and ad hoc, it did provide me with a taste of a kind of happiness that did not come from simply satisfying the five senses or attaining worldly goals. This nascent interest in the spiritual dimension of life that was there since childhood became progressively more prominent as I grew older.

My parents were Thai, but I grew up mainly in the Philippines and lived there until I finished secondary school, whereupon I went to the U.S. to do my bachelor’s degree. Living in the very-Catholic Philippines, I grew up accustomed to seeing images of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ, watching cartoons about the Bible, and loving the Christmas season (not just for the gifts). One of my earliest happy childhood memories was playing with the Catholic sisters at the convent just down the street from our home. Yet for some reason I never felt particularly drawn to Christianity.

Within our family, my mother had an interest in the Dhamma, which deepened as the years passed. Every year during school holidays we would return to Thailand to visit family, and occasionally my mother would take my sister and me to visit a Buddhist temple. For me, going to the temple was something special, not something I took for granted as I might have had I grown up in Thailand. I enjoyed it, as I would leave the temple feeling happy and peaceful. When I was nine or ten, my mother also galvanized my sister and me to do Buddhist chanting and a little meditation every day, although it devolved to once a week before too long. I ended up only doing some abbreviated chanting before bed, but I remember really liking this activity. Even though I didn’t understand what we were chanting, as it was all in Pali, I found the chanting was soothing (and even kind of fun) and the meditation calming.

I started to question what so-called intelligence really was. It seemed to me that if a person were truly intelligent, they would know how to be happy.

Growing up, I also had a natural affinity for the actual teachings of the Buddha and wanted to learn more about them. For instance, completely on my own, with no prompting from anyone else, I chose to write a research paper in high school comparing the teachings in the major schools of Buddhism. However, it was not until university that I really looked to the Dhamma out of an earnest need of the heart. I was at Harvard, where supposedly everyone was very intelligent. Yet it struck me that most of the people walking around campus (myself included) sure didn’t seem very happy. Mostly, people seemed stressed and obsessed about what they needed to do to succeed and achieve or even just to survive the daily grind. I started to question what so-called intelligence really was. It seemed to me that if a person were truly intelligent, they would know how to be happy.

Fortunately, because of my positive childhood experiences with Buddhism and my mother’s interest in the Dhamma, I had a spiritual resource to turn to when the going got tough, rather than looking to alcohol or drugs, or worse. When I became severely depressed in my second year at university, upon my mother’s urging, I went to a Buddhist monastery, where the friendly monk gave me an English translation of Buddhadasa Bhikkhu’s Buddhadhamma for Students. Although depression is no party in the park, looking back, I see it was an invaluable experience because it pushed me to the point where, for the first time in my life, I started asking the big questions. I was surprised I had lived as long as I had without ever thinking to ask, Why are we born? What are the most important things to do in life? What is a meaningful life? A life well led? So I read the Dhamma with a new kind of urgency, desperately searching for a way out of my misery and some answers to these questions. Reading that book by Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, I was particularly taken with one sentence where he said that all of the Buddha’s teachings, though vast, can be summarized into just two things: suffering and the end of suffering.

That brought me clarity. Right. So, really the point of life was to end suffering. That certainly resonated with my experience of acute unhappiness at the time, when what plainly mattered the most was somehow getting out of it. And there was a somehow—the Noble Eightfold Path—a path that wouldn’t simply educate the brain, but one that would train the heart. So from that time on, I knew that ultimately the most important thing to do in life was to study and practice the Dhamma, to use this life to take further steps along the Path and grow in the Dhamma, and to work toward the ending of all suffering—both for myself and others.

Feminine Buddha at Wat-Thepthidaram photodharma.net/Thailand/Wat-Thepthidaram/ Wat-Thepthidaram.htm

Thus, the priceless gift the Buddha’s teachings gave me was a clear sense of purpose in life and a path to follow. Not just any path, but “a path secure.” Once one has that in life, no matter how bad things get, at some deep level one has an internal pillar of strength, an anchor to keep one moored amidst life’s vicissitudes. Because really, one of the worst kinds of suffering in life is not that which comes from a particularly tragic situation or grave disappointment, but the suffering of being lost without direction, groping around blindly in a terrible, confused muddle, not knowing whether to turn left or right, step forward or back. While treading the Path is challenging, just by getting on it, a whole heap of suffering is shed.

However, in my early twenties, while I had the vague notion that eventually I would like to get serious about the Dhamma, I still wanted to experience having normal worldly fun and get it out of my system. For a few years I lived it up as a young person, working and cavorting in one of the most happening places in the world, New York City. But it didn’t take long to see the limits of that sort of fun and grow weary of it. So in my last year in the city I started attending meditation classes and volunteering at the New York Insight Meditation Center.

When I returned to Thailand at the age of twenty-five, my mother became seriously ill with a terminal condition, which made the concept of mortality a much more immediate reality to me. I asked myself, Who knows when you’re going to die? How much longer are you going to wait before you get serious about the Dhamma? And now that I was back in Thailand, the land o’ plenty in terms of Buddhist resources, there were ample opportunities to learn and practice the Dhamma. I started reading more about the Dhamma, attending Dhamma talks, going on meditation retreat courses, and visiting temples.

Over the years, as I became more and more engaged in Dhamma practice, I found the methods it provided for training the mind were having a gradual but noticeable effect of greater awareness and groundedness. However, I also started to feel certain conflicts and limits in trying to practice more seriously as a lay woman, when the activities and values I was giving greater priority to were at odds with what most people around me and the society at large were geared toward. At the same time, on a broader level, there was a trend emerging in contemporary Buddhism—not only in the West but also in Thailand—of growing laicization, with lay practitioners feeling more empowered to study, practice, and teach the Dhamma themselves, bypassing the need for monks, temples, and ordination. Yet to me there seemed to be something strange about that. There seemed to be inherent ambiguities and contradictions in the lives of committed lay practitioners, and an obscuration of the real and significant differences that exist between practicing as a lay woman or man and practicing as a monastic. I was so intrigued by this issue that I wrote my master’s degree thesis about it, with the project serving not only to produce a piece of academic research but to enable me to reflect on these issues personally.

While every person is different and will find different pathways suitable for their particular life circumstances, for me personally, I felt increasingly drawn to the monastic life. When I started seriously thinking of ordaining and worked up the courage to actually voice my aspiration to people, I was met with support from some, but also opposition, skepticism, and discouragement from others. One monk said to me, “It is better being a lay woman because you have more freedom than if you ordain.” But I thought, well, that’s exactly why I want to ordain—there’s too much freedom as a lay woman! But it’s a phony kind of freedom. Yes, you are ostensibly free to do whatever you want, but what this really means is that you are bound to the tyranny of your kilesas (mental defilements), at the beck and call of the forces of greed, hatred, and delusion in your mind. True freedom, however, would be freedom from the kilesas.

A good case in point was my losing battle with potato chips. Yes, I was completely free to pop down to the 7-Eleven store down the road whenever I had a craving for those shiny little packages of chips (or what should be called “colon cancer in a bag”). But I was completely powerless to say no to Master Kilesa commanding me to do that. In the spectrum of vices, I suppose junk food is relatively mild, but my inability to get the better of my compulsion to eat ungodly amounts of what I rationally knew were unhealthy foods is emblematic of the essential difficulties anyone faces trying to train the mind and tame the kilesas without the support of conducive conditions.

Sila (virtue) is one of the great supports. In my last year as a lay woman, I started keeping the eight precepts once a week on the Buddhist holy day, and I honestly felt so blessed—saved, even—especially by the one about not eating solid foods after noon. Rather than struggling so hard to hold at bay the late-night potato chip demons by myself, as I did, mostly unsuccessfully, the other six days of the week, I had the precepts as a ready-made wall to keep them out. They had no way to get close enough for me to have to deal with them. So I don’t feel like more precepts caused me more hassle, but rather, more freedom. Or to be more precise, the precepts were external restrictions that worked as the means to bring about greater internal freedom.

Thus, the notion of taking on more precepts (the ten of a samaneri, or novice nun), not just once a week, but all the time, seemed like a very good idea indeed. Although I may have had some karmic reasons for being attracted to monastic life, I also had very rational reasons for wanting to ordain: basically, I had good reason to believe that the monastic way of life would be an excellent support in the study and practice of Dhamma.

A happy mind is nothing other than a wholesome mind

It has now been almost three months since my going forth as a samaneri, and while this is a very modest amount of time in robes, I would say my personal experience so far has borne this out to be true, and in so many more ways than I had ever even imagined beforehand. If I were to encapsulate the manifold blessings I have gained from being ordained into one basic idea, it would be this: it is just so much easier to practice Right Effort, preventing unwholesome mind states from arising, abandoning unwholesome mind states that have arisen, encouraging wholesome mind states that have not arisen to arise, and nurturing wholesome mind states that have arisen that they may expand to their full development. After all, a happy mind is nothing other than a wholesome mind.

It is not just the greater precepts but the whole way of life and setup of the monastery that is designed to help support your growth in the Dhamma. So to play out the potato chip example further, it is immensely helpful not only that the precepts bar eating after midday, but also that the kitchen is closed. You don’t see food laying around, you don’t see anyone else snacking or inviting you to snack, you have all sorts of other wholesome activities to be occupying you at night and keeping your mind off food (what with the daily evening chanting, group meditation, and Dhamma talk routine). You can imagine your teacher fixing you with that disapproving eye if she ever caught you “illegally” snacking; you can imagine the disappointment of your monastic fellows, especially your juniors, if they saw you do it; and more importantly, you yourself would feel much more shame doing it now that you are wearing the robes and living on the generous donations of the laity.

In addition, living in an environment surrounded by the Dhamma, the Dhamma starts to seep into your mind in a more sustained and effective way than when you are living in the heart of, say, Bangkok inundated by the marketing messages of modern consumer culture. It is like trying to learn a foreign language. When you take a one-hour class once a week, or even every day, you could be studying for years and make only slow and choppy progress. But if you go and live in a place where you are totally immersed in that language, where you have to live and breathe that language, you can learn it so much more easily and quickly. That is what it is like when you ordain: you are fully living and breathing the language of the Dhamma.

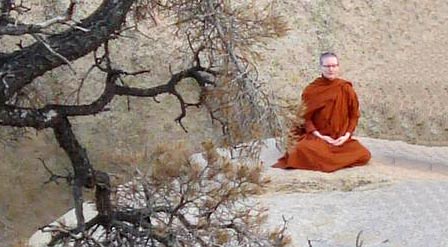

Another very important benefit I have gained from monastic life is the opportunity to undertake longer periods of meditation retreat than was possible as a lay woman. Moreover, they are retreats empowered by the foundation of an existing lifestyle of renunciation, unlike the somewhat artificial meditation breaks taken out of normal lay life. I feel very grateful for those retreat opportunities generously granted me by my teacher and kindly supported by my monastic community. Those times spent devoting yourself to formal meditation practice in a more sustained and continuous way without external distractions can really give a boost to practice. When the mind becomes more subtle and clear, as can happen on retreat, it is possible to gain a deeper understanding of the workings of the mind and the true nature of all things. The chance to hone meditation skills while on retreat also can lead to greater facility in maintaining mindfulness and wholesome mind-states on a daily basis outside of retreat.

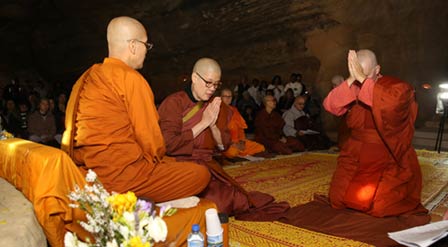

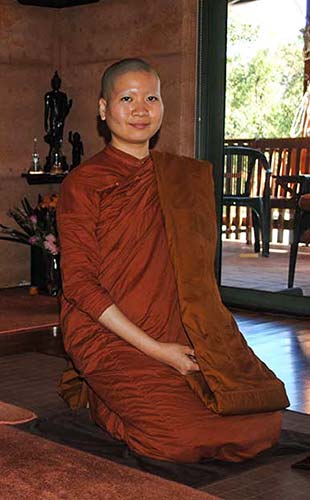

While the benefits of ordaining as a samaneri have been immense and profound, after taking bhikkhuni ordination I have felt even more powerfully supported in my practice. I remember when I was a lay woman staying at a monastery in Thailand, all the monastery residents would convene to do morning chanting together. Whenever we got to the part at the end where all the laity remained silent and the monks alone would chant, “Like the Blessed One, we practice the Holy Life, being fully equipped with the bhikkhus’ system of training (Tasmim bhagavati brahmacariyam carama/Bhikkhunam sikkha sajivasamapanna),” I would feel a dagger in the heart. I felt so sad that women didn’t have such an opportunity and really wished one day we could. I feel so grateful and incredibly blessed that now I, and increasing numbers of other women, have been able to take higher ordination and can likewise be fully equipped with the bhikkhunis’ system of training.

People have asked me whether I feel keeping the bhikkhuni precepts (311 rules in the Theravada tradition) is troublesome or restrictive. Yes, they are restrictive. Wonderfully restrictive! Totally worth any minor trouble involved in keeping them. How I feel about the bhikkhuni precepts is much the same as how I felt about the samaneri precepts, only exponentially more so—that is, an even more amazing blessing and help! Again, what the rules are restricting is not your freedom, but your kilesas. More rules of restraint create an ever-finer sieve to keep out more and more refined defilements.

Even as an “infant” bhikkhuni of merely three months, I find having the bhikkhuni rules to work with has given so much more meat to the practice. Developing continuous mindfulness is very much aided by having more rules that impinge on the specifics of daily life. They add more concrete pegs to hang mindfulness on—simple, practical things you have to bring to mind at regular intervals rather than just floating through the day vaguely trying to maintain mindfulness. For example: “Gee, has this edible item been offered? When? For how long can it be used?”

Having more rules also means you have more things to bump up against, more often. Every time you are faced with a situation in which a rule applies, you have the chance to see the mind and any kilesas that pop up. You are able to look at why you might feel resistance to keeping a certain rule, whether it is laziness or greed or stubborn attachment to your ideas or whatever. It is easier to see the defilements in detail when you have these situational lenses to focus on them. You can’t let go of defilements if you don’t even know they’re there. But every time that you can let go, every time you choose to keep the rules despite the objections of your defilements, you are reaffirming your commitment to the Path. Also, as in most cases, intention is an important factor in deciding whether you have committed an offence: you are able to practice becoming sharper and clearer about what your intentions are in doing something.

Having more rules also means you have more things to bump up against, more often. Every time you are faced with a situation in which a rule applies, you have the chance to see the mind and any kilesas that pop up. You are able to look at why you might feel resistance to keeping a certain rule, whether it is laziness or greed or stubborn attachment to your ideas or whatever. It is easier to see the defilements in detail when you have these situational lenses to focus on them. You can’t let go of defilements if you don’t even know they’re there. But every time that you can let go, every time you choose to keep the rules despite the objections of your defilements, you are reaffirming your commitment to the Path. Also, as in most cases, intention is an important factor in deciding whether you have committed an offence: you are able to practice becoming sharper and clearer about what your intentions are in doing something.

Learning about and practicing the Vinaya also helps you to develop wisdom, through the process of figuring out what the real spirit of the rules are and how to keep them in a sensible way, striking the balance between the unhelpful extremes of being overly loose or overly rigid.

During the recitation of the Patimokkha (which I feel so happy to be able to take part in), or just whenever I review the rules myself, I always feel deeply moved when I get to Bhikkhuni Pacittiya Twenty: “Should any bhikkhuni weep, beating and beating herself, it is to be confessed.” That rule in particular clearly captures the spirit of the Vinaya for me—they are not draconian commandments to oppress or arcane rules to make life difficult, but compassionate measures the Buddha so caringly and patiently devised as safeguards to protect his children from causing harm to themselves or others.

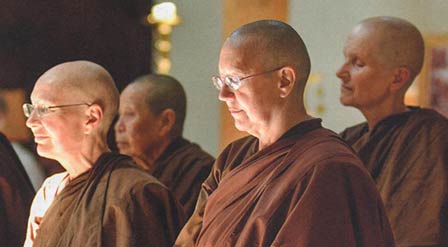

It was especially valuable to finally have spiritual role models who were female. Previously, I could only look to monks as role models, but no matter how wise or compassionate they were, there was still a subconscious disconnect because I just couldn’t see myself in them.

Indeed, living with the bhikkhuni rules has made me feel closer to the Buddha, who now feels less and less like a statue and more and more like a real person; who, as father of the sangha, watched over the monks and nuns and lovingly helped to solve their problems and establish them securely. Bhikkhuni ordination has also made me feel closer to the sangha, for really the word ordination is not an accurate a translation of the Pali term upasampada, meaning “acceptance.” As I was reminded at my upasampada, I have now been accepted as a full member of the sangha, with full rights as well as full responsibilities.

Even prior to bhikkhuni ordination, as a samaneri I had already reaped enormous benefit from the Bhikkhuni Sangha. I feel tremendously grateful to Nirodharam Bhikkhuni Arama, under the compassionate guidance of Phra Ajahn Nandayani, for giving me the precious opportunity to go forth as a samaneri, then supporting me in my training as a novice nun. It is rare to find a place in Thailand that will fully support women to keep the ten precepts. It is also rare to find a place that has a large and thriving all-female monastic community. It feels very different living as a woman in a monk’s monastery versus living as a woman, especially as a nun, in a nun’s monastery. At a basic level, there is such a feeling of ease and comfort. Rather than always being on guard, trying to be as invisible and unobtrusive as possible at Nirodharam even when I was just a lay visitor, I could feel relaxed and free to go anywhere in the monastery and to relate casually with the nuns. Once I became a nun myself, I felt even closer to the other nuns, who felt like kind aunties or elder and younger sisters.

It was especially valuable to finally have spiritual role models who were female. Previously, I could only look to monks as role models, but no matter how wise or compassionate they were, there was still a subconscious disconnect because I just couldn’t see myself in them. With Phra Ajahn Nandayani, however, I could be inspired by an example of someone who was a woman just like me, but unlike me, was clearly advanced in her practice, which gave me living proof that somehow it could be done in female form.

I am particularly indebted to Phra Ajahn for her tireless efforts to convey the Buddha’s teachings to her students. Whether through her talks or the manuals, she puts much toil into producing for our benefit. Her ability to explain a wide range of Dhamma teachings in ways that are easy to understand and remember have been an invaluable help in my Dhamma education. More than that, being able to observe her at close hand in both formal and informal situations (which is much more difficult to do with monk teachers) has given me many real-life teachings in how to act, speak, and think. Conversely, being observed by her vigilant eagle eye is a great blessing because it is very rare indeed to find someone who will care enough to correct you.

However, it was not just Phra Ajahn who was my teacher at Nirodharam. I was also taught and inspired by the other nuns, whether they were my elders, peers, or juniors, as they exemplified so many beautiful qualities of the heart. Being able to live close to them in a warm and caring community, I was able to learn so much, and hopefully absorb something, from their wonderful examples.

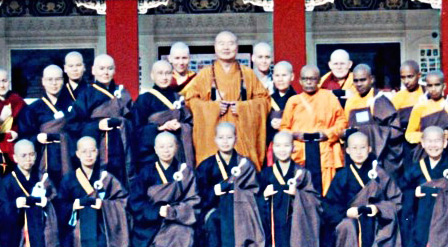

I have also gained much from the wider Bhikkhuni Sangha outside of Nirodharam. I love the phrase Sangha of the Four Quarters. For me, one of the most beautiful aspects of the bhikkhuni order is that it is a timeless, boundary-less sisterhood. It does not hinge on any particular teacher (aside from the Buddha) or monastery or nation-state. It is very touching to see how the bhikkhunis around the world have been helping each other in this pioneering effort of reviving the Theravada Bhikkhuni Sangha. I felt this particularly keenly with my own higher ordination, seeing the great goodwill and generosity of bhikkhunis who readily lent their hand to help a sister—not even from their monastery or country—receive acceptance. I am profoundly grateful to my preceptor, Ayya Tathaaloka from the United States, for bringing it about and also to all the other bhikkhunis and samaneris from America and the far corners of Australia who were involved, particularly the community at Dhammasara Monastery for graciously hosting the ordination. I am also grateful to my teacher and the community at Nirodharam for giving their moral support and rejoicing on my behalf.

I have felt very encouraged hearing many bhikkhus saying to bhikkhunis, “Great, you can help us do the work of dispensation, the Sasana.”

Yet by taking bhikkhuni ordination one is accepted not just into the Bhikkhuni Sangha, but also into the ubato sangha (dual sangha) of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis. It meant a great deal to me to be welcomed into the sangha by the bhikkhu brothers as well. I now feel like part of a big, warm family where all us kids, brothers and sisters alike, are trying to help Dad with the family business: Buddhasasana, Inc. (that is, incorporating both males and females, but totally nonprofit, of course). I have felt very encouraged hearing many bhikkhus saying to bhikkhunis, “Great, you can help us do the work of dispensation, the Sasana.” We owe so much to the Bhikkhu Sangha, who for centuries in the Theravada tradition has been shouldering the great workload largely by themselves, preserving and passing on the Dhamma up until the present time. In these early days of the revived Bhikkhuni Sangha, the Bhikkhu Sangha has also been helping tremendously in facilitating or quietly supporting the ordination of bhikkhunis, as well as providing us with teaching and guidance. I feel very grateful for this support and hope that as we bhikkhunis grow and mature, we will be able to do more and more to help our bhikkhu brothers to serve the Sasana. May we all work together to help ever more beings, including ourselves, find liberation from suffering.

From the December 2012 edition of Present

My passport says I am Thai, but actually I have lived most of my life outside of predominantly-Buddhist Thailand. Although my contact with Buddhist-y things growing up was thus quite limited and ad hoc, it did provide me with a taste of a kind of happiness that did not come from simply satisfying the five senses or attaining worldly goals. This nascent interest in the spiritual dimension of life that was there since childhood became progressively more prominent as I grew older.

My parents were Thai, but I grew up mainly in the Philippines and lived there until I finished secondary school, whereupon I went to the U.S. to do my bachelor’s degree. Living in the very-Catholic Philippines, I grew up accustomed to seeing images of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ, watching cartoons about the Bible, and loving the Christmas season (not just for the gifts). One of my earliest happy childhood memories was playing with the Catholic sisters at the convent just down the street from our home. Yet for some reason I never felt particularly drawn to Christianity.

Within our family, my mother had an interest in the Dhamma, which deepened as the years passed. Every year during school holidays we would return to Thailand to visit family, and occasionally my mother would take my sister and me to visit a Buddhist temple. For me, going to the temple was something special, not something I took for granted as I might have had I grown up in Thailand. I enjoyed it, as I would leave the temple feeling happy and peaceful. When I was nine or ten, my mother also galvanized my sister and me to do Buddhist chanting and a little meditation every day, although it devolved to once a week before too long. I ended up only doing some abbreviated chanting before bed, but I remember really liking this activity. Even though I didn’t understand what we were chanting, as it was all in Pali, I found the chanting was soothing (and even kind of fun) and the meditation calming.

I started to question what so-called intelligence really was. It seemed to me that if a person were truly intelligent, they would know how to be happy.

Growing up, I also had a natural affinity for the actual teachings of the Buddha and wanted to learn more about them. For instance, completely on my own, with no prompting from anyone else, I chose to write a research paper in high school comparing the teachings in the major schools of Buddhism. However, it was not until university that I really looked to the Dhamma out of an earnest need of the heart. I was at Harvard, where supposedly everyone was very intelligent. Yet it struck me that most of the people walking around campus (myself included) sure didn’t seem very happy. Mostly, people seemed stressed and obsessed about what they needed to do to succeed and achieve or even just to survive the daily grind. I started to question what so-called intelligence really was. It seemed to me that if a person were truly intelligent, they would know how to be happy.

Fortunately, because of my positive childhood experiences with Buddhism and my mother’s interest in the Dhamma, I had a spiritual resource to turn to when the going got tough, rather than looking to alcohol or drugs, or worse. When I became severely depressed in my second year at university, upon my mother’s urging, I went to a Buddhist monastery, where the friendly monk gave me an English translation of Buddhadasa Bhikkhu’s Buddhadhamma for Students. Although depression is no party in the park, looking back, I see it was an invaluable experience because it pushed me to the point where, for the first time in my life, I started asking the big questions. I was surprised I had lived as long as I had without ever thinking to ask, Why are we born? What are the most important things to do in life? What is a meaningful life? A life well led? So I read the Dhamma with a new kind of urgency, desperately searching for a way out of my misery and some answers to these questions. Reading that book by Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, I was particularly taken with one sentence where he said that all of the Buddha’s teachings, though vast, can be summarized into just two things: suffering and the end of suffering.

That brought me clarity. Right. So, really the point of life was to end suffering. That certainly resonated with my experience of acute unhappiness at the time, when what plainly mattered the most was somehow getting out of it. And there was a somehow—the Noble Eightfold Path—a path that wouldn’t simply educate the brain, but one that would train the heart. So from that time on, I knew that ultimately the most important thing to do in life was to study and practice the Dhamma, to use this life to take further steps along the Path and grow in the Dhamma, and to work toward the ending of all suffering—both for myself and others.

Feminine Buddha at Wat-Thepthidaram photodharma.net/Thailand/Wat-Thepthidaram/ Wat-Thepthidaram.htm

Thus, the priceless gift the Buddha’s teachings gave me was a clear sense of purpose in life and a path to follow. Not just any path, but “a path secure.” Once one has that in life, no matter how bad things get, at some deep level one has an internal pillar of strength, an anchor to keep one moored amidst life’s vicissitudes. Because really, one of the worst kinds of suffering in life is not that which comes from a particularly tragic situation or grave disappointment, but the suffering of being lost without direction, groping around blindly in a terrible, confused muddle, not knowing whether to turn left or right, step forward or back. While treading the Path is challenging, just by getting on it, a whole heap of suffering is shed.

However, in my early twenties, while I had the vague notion that eventually I would like to get serious about the Dhamma, I still wanted to experience having normal worldly fun and get it out of my system. For a few years I lived it up as a young person, working and cavorting in one of the most happening places in the world, New York City. But it didn’t take long to see the limits of that sort of fun and grow weary of it. So in my last year in the city I started attending meditation classes and volunteering at the New York Insight Meditation Center.

When I returned to Thailand at the age of twenty-five, my mother became seriously ill with a terminal condition, which made the concept of mortality a much more immediate reality to me. I asked myself, Who knows when you’re going to die? How much longer are you going to wait before you get serious about the Dhamma? And now that I was back in Thailand, the land o’ plenty in terms of Buddhist resources, there were ample opportunities to learn and practice the Dhamma. I started reading more about the Dhamma, attending Dhamma talks, going on meditation retreat courses, and visiting temples.

Over the years, as I became more and more engaged in Dhamma practice, I found the methods it provided for training the mind were having a gradual but noticeable effect of greater awareness and groundedness. However, I also started to feel certain conflicts and limits in trying to practice more seriously as a lay woman, when the activities and values I was giving greater priority to were at odds with what most people around me and the society at large were geared toward. At the same time, on a broader level, there was a trend emerging in contemporary Buddhism—not only in the West but also in Thailand—of growing laicization, with lay practitioners feeling more empowered to study, practice, and teach the Dhamma themselves, bypassing the need for monks, temples, and ordination. Yet to me there seemed to be something strange about that. There seemed to be inherent ambiguities and contradictions in the lives of committed lay practitioners, and an obscuration of the real and significant differences that exist between practicing as a lay woman or man and practicing as a monastic. I was so intrigued by this issue that I wrote my master’s degree thesis about it, with the project serving not only to produce a piece of academic research but to enable me to reflect on these issues personally.

While every person is different and will find different pathways suitable for their particular life circumstances, for me personally, I felt increasingly drawn to the monastic life. When I started seriously thinking of ordaining and worked up the courage to actually voice my aspiration to people, I was met with support from some, but also opposition, skepticism, and discouragement from others. One monk said to me, “It is better being a lay woman because you have more freedom than if you ordain.” But I thought, well, that’s exactly why I want to ordain—there’s too much freedom as a lay woman! But it’s a phony kind of freedom. Yes, you are ostensibly free to do whatever you want, but what this really means is that you are bound to the tyranny of your kilesas (mental defilements), at the beck and call of the forces of greed, hatred, and delusion in your mind. True freedom, however, would be freedom from the kilesas.

A good case in point was my losing battle with potato chips. Yes, I was completely free to pop down to the 7-Eleven store down the road whenever I had a craving for those shiny little packages of chips (or what should be called “colon cancer in a bag”). But I was completely powerless to say no to Master Kilesa commanding me to do that. In the spectrum of vices, I suppose junk food is relatively mild, but my inability to get the better of my compulsion to eat ungodly amounts of what I rationally knew were unhealthy foods is emblematic of the essential difficulties anyone faces trying to train the mind and tame the kilesas without the support of conducive conditions.

Sila (virtue) is one of the great supports. In my last year as a lay woman, I started keeping the eight precepts once a week on the Buddhist holy day, and I honestly felt so blessed—saved, even—especially by the one about not eating solid foods after noon. Rather than struggling so hard to hold at bay the late-night potato chip demons by myself, as I did, mostly unsuccessfully, the other six days of the week, I had the precepts as a ready-made wall to keep them out. They had no way to get close enough for me to have to deal with them. So I don’t feel like more precepts caused me more hassle, but rather, more freedom. Or to be more precise, the precepts were external restrictions that worked as the means to bring about greater internal freedom.

Thus, the notion of taking on more precepts (the ten of a samaneri, or novice nun), not just once a week, but all the time, seemed like a very good idea indeed. Although I may have had some karmic reasons for being attracted to monastic life, I also had very rational reasons for wanting to ordain: basically, I had good reason to believe that the monastic way of life would be an excellent support in the study and practice of Dhamma.

A happy mind is nothing other than a wholesome mind

It has now been almost three months since my going forth as a samaneri, and while this is a very modest amount of time in robes, I would say my personal experience so far has borne this out to be true, and in so many more ways than I had ever even imagined beforehand. If I were to encapsulate the manifold blessings I have gained from being ordained into one basic idea, it would be this: it is just so much easier to practice Right Effort, preventing unwholesome mind states from arising, abandoning unwholesome mind states that have arisen, encouraging wholesome mind states that have not arisen to arise, and nurturing wholesome mind states that have arisen that they may expand to their full development. After all, a happy mind is nothing other than a wholesome mind.

It is not just the greater precepts but the whole way of life and setup of the monastery that is designed to help support your growth in the Dhamma. So to play out the potato chip example further, it is immensely helpful not only that the precepts bar eating after midday, but also that the kitchen is closed. You don’t see food laying around, you don’t see anyone else snacking or inviting you to snack, you have all sorts of other wholesome activities to be occupying you at night and keeping your mind off food (what with the daily evening chanting, group meditation, and Dhamma talk routine). You can imagine your teacher fixing you with that disapproving eye if she ever caught you “illegally” snacking; you can imagine the disappointment of your monastic fellows, especially your juniors, if they saw you do it; and more importantly, you yourself would feel much more shame doing it now that you are wearing the robes and living on the generous donations of the laity.

In addition, living in an environment surrounded by the Dhamma, the Dhamma starts to seep into your mind in a more sustained and effective way than when you are living in the heart of, say, Bangkok inundated by the marketing messages of modern consumer culture. It is like trying to learn a foreign language. When you take a one-hour class once a week, or even every day, you could be studying for years and make only slow and choppy progress. But if you go and live in a place where you are totally immersed in that language, where you have to live and breathe that language, you can learn it so much more easily and quickly. That is what it is like when you ordain: you are fully living and breathing the language of the Dhamma.

Another very important benefit I have gained from monastic life is the opportunity to undertake longer periods of meditation retreat than was possible as a lay woman. Moreover, they are retreats empowered by the foundation of an existing lifestyle of renunciation, unlike the somewhat artificial meditation breaks taken out of normal lay life. I feel very grateful for those retreat opportunities generously granted me by my teacher and kindly supported by my monastic community. Those times spent devoting yourself to formal meditation practice in a more sustained and continuous way without external distractions can really give a boost to practice. When the mind becomes more subtle and clear, as can happen on retreat, it is possible to gain a deeper understanding of the workings of the mind and the true nature of all things. The chance to hone meditation skills while on retreat also can lead to greater facility in maintaining mindfulness and wholesome mind-states on a daily basis outside of retreat.

While the benefits of ordaining as a samaneri have been immense and profound, after taking bhikkhuni ordination I have felt even more powerfully supported in my practice. I remember when I was a lay woman staying at a monastery in Thailand, all the monastery residents would convene to do morning chanting together. Whenever we got to the part at the end where all the laity remained silent and the monks alone would chant, “Like the Blessed One, we practice the Holy Life, being fully equipped with the bhikkhus’ system of training (Tasmim bhagavati brahmacariyam carama/Bhikkhunam sikkha sajivasamapanna),” I would feel a dagger in the heart. I felt so sad that women didn’t have such an opportunity and really wished one day we could. I feel so grateful and incredibly blessed that now I, and increasing numbers of other women, have been able to take higher ordination and can likewise be fully equipped with the bhikkhunis’ system of training.

People have asked me whether I feel keeping the bhikkhuni precepts (311 rules in the Theravada tradition) is troublesome or restrictive. Yes, they are restrictive. Wonderfully restrictive! Totally worth any minor trouble involved in keeping them. How I feel about the bhikkhuni precepts is much the same as how I felt about the samaneri precepts, only exponentially more so—that is, an even more amazing blessing and help! Again, what the rules are restricting is not your freedom, but your kilesas. More rules of restraint create an ever-finer sieve to keep out more and more refined defilements.

Even as an “infant” bhikkhuni of merely three months, I find having the bhikkhuni rules to work with has given so much more meat to the practice. Developing continuous mindfulness is very much aided by having more rules that impinge on the specifics of daily life. They add more concrete pegs to hang mindfulness on—simple, practical things you have to bring to mind at regular intervals rather than just floating through the day vaguely trying to maintain mindfulness. For example: “Gee, has this edible item been offered? When? For how long can it be used?”

Having more rules also means you have more things to bump up against, more often. Every time you are faced with a situation in which a rule applies, you have the chance to see the mind and any kilesas that pop up. You are able to look at why you might feel resistance to keeping a certain rule, whether it is laziness or greed or stubborn attachment to your ideas or whatever. It is easier to see the defilements in detail when you have these situational lenses to focus on them. You can’t let go of defilements if you don’t even know they’re there. But every time that you can let go, every time you choose to keep the rules despite the objections of your defilements, you are reaffirming your commitment to the Path. Also, as in most cases, intention is an important factor in deciding whether you have committed an offence: you are able to practice becoming sharper and clearer about what your intentions are in doing something.

Having more rules also means you have more things to bump up against, more often. Every time you are faced with a situation in which a rule applies, you have the chance to see the mind and any kilesas that pop up. You are able to look at why you might feel resistance to keeping a certain rule, whether it is laziness or greed or stubborn attachment to your ideas or whatever. It is easier to see the defilements in detail when you have these situational lenses to focus on them. You can’t let go of defilements if you don’t even know they’re there. But every time that you can let go, every time you choose to keep the rules despite the objections of your defilements, you are reaffirming your commitment to the Path. Also, as in most cases, intention is an important factor in deciding whether you have committed an offence: you are able to practice becoming sharper and clearer about what your intentions are in doing something.

Learning about and practicing the Vinaya also helps you to develop wisdom, through the process of figuring out what the real spirit of the rules are and how to keep them in a sensible way, striking the balance between the unhelpful extremes of being overly loose or overly rigid.

During the recitation of the Patimokkha (which I feel so happy to be able to take part in), or just whenever I review the rules myself, I always feel deeply moved when I get to Bhikkhuni Pacittiya Twenty: “Should any bhikkhuni weep, beating and beating herself, it is to be confessed.” That rule in particular clearly captures the spirit of the Vinaya for me—they are not draconian commandments to oppress or arcane rules to make life difficult, but compassionate measures the Buddha so caringly and patiently devised as safeguards to protect his children from causing harm to themselves or others.

It was especially valuable to finally have spiritual role models who were female. Previously, I could only look to monks as role models, but no matter how wise or compassionate they were, there was still a subconscious disconnect because I just couldn’t see myself in them.

Indeed, living with the bhikkhuni rules has made me feel closer to the Buddha, who now feels less and less like a statue and more and more like a real person; who, as father of the sangha, watched over the monks and nuns and lovingly helped to solve their problems and establish them securely. Bhikkhuni ordination has also made me feel closer to the sangha, for really the word ordination is not an accurate a translation of the Pali term upasampada, meaning “acceptance.” As I was reminded at my upasampada, I have now been accepted as a full member of the sangha, with full rights as well as full responsibilities.

Even prior to bhikkhuni ordination, as a samaneri I had already reaped enormous benefit from the Bhikkhuni Sangha. I feel tremendously grateful to Nirodharam Bhikkhuni Arama, under the compassionate guidance of Phra Ajahn Nandayani, for giving me the precious opportunity to go forth as a samaneri, then supporting me in my training as a novice nun. It is rare to find a place in Thailand that will fully support women to keep the ten precepts. It is also rare to find a place that has a large and thriving all-female monastic community. It feels very different living as a woman in a monk’s monastery versus living as a woman, especially as a nun, in a nun’s monastery. At a basic level, there is such a feeling of ease and comfort. Rather than always being on guard, trying to be as invisible and unobtrusive as possible at Nirodharam even when I was just a lay visitor, I could feel relaxed and free to go anywhere in the monastery and to relate casually with the nuns. Once I became a nun myself, I felt even closer to the other nuns, who felt like kind aunties or elder and younger sisters.

It was especially valuable to finally have spiritual role models who were female. Previously, I could only look to monks as role models, but no matter how wise or compassionate they were, there was still a subconscious disconnect because I just couldn’t see myself in them. With Phra Ajahn Nandayani, however, I could be inspired by an example of someone who was a woman just like me, but unlike me, was clearly advanced in her practice, which gave me living proof that somehow it could be done in female form.

I am particularly indebted to Phra Ajahn for her tireless efforts to convey the Buddha’s teachings to her students. Whether through her talks or the manuals, she puts much toil into producing for our benefit. Her ability to explain a wide range of Dhamma teachings in ways that are easy to understand and remember have been an invaluable help in my Dhamma education. More than that, being able to observe her at close hand in both formal and informal situations (which is much more difficult to do with monk teachers) has given me many real-life teachings in how to act, speak, and think. Conversely, being observed by her vigilant eagle eye is a great blessing because it is very rare indeed to find someone who will care enough to correct you.

However, it was not just Phra Ajahn who was my teacher at Nirodharam. I was also taught and inspired by the other nuns, whether they were my elders, peers, or juniors, as they exemplified so many beautiful qualities of the heart. Being able to live close to them in a warm and caring community, I was able to learn so much, and hopefully absorb something, from their wonderful examples.

I have also gained much from the wider Bhikkhuni Sangha outside of Nirodharam. I love the phrase Sangha of the Four Quarters. For me, one of the most beautiful aspects of the bhikkhuni order is that it is a timeless, boundary-less sisterhood. It does not hinge on any particular teacher (aside from the Buddha) or monastery or nation-state. It is very touching to see how the bhikkhunis around the world have been helping each other in this pioneering effort of reviving the Theravada Bhikkhuni Sangha. I felt this particularly keenly with my own higher ordination, seeing the great goodwill and generosity of bhikkhunis who readily lent their hand to help a sister—not even from their monastery or country—receive acceptance. I am profoundly grateful to my preceptor, Ayya Tathaaloka from the United States, for bringing it about and also to all the other bhikkhunis and samaneris from America and the far corners of Australia who were involved, particularly the community at Dhammasara Monastery for graciously hosting the ordination. I am also grateful to my teacher and the community at Nirodharam for giving their moral support and rejoicing on my behalf.

I have felt very encouraged hearing many bhikkhus saying to bhikkhunis, “Great, you can help us do the work of dispensation, the Sasana.”

Yet by taking bhikkhuni ordination one is accepted not just into the Bhikkhuni Sangha, but also into the ubato sangha (dual sangha) of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis. It meant a great deal to me to be welcomed into the sangha by the bhikkhu brothers as well. I now feel like part of a big, warm family where all us kids, brothers and sisters alike, are trying to help Dad with the family business: Buddhasasana, Inc. (that is, incorporating both males and females, but totally nonprofit, of course). I have felt very encouraged hearing many bhikkhus saying to bhikkhunis, “Great, you can help us do the work of dispensation, the Sasana.” We owe so much to the Bhikkhu Sangha, who for centuries in the Theravada tradition has been shouldering the great workload largely by themselves, preserving and passing on the Dhamma up until the present time. In these early days of the revived Bhikkhuni Sangha, the Bhikkhu Sangha has also been helping tremendously in facilitating or quietly supporting the ordination of bhikkhunis, as well as providing us with teaching and guidance. I feel very grateful for this support and hope that as we bhikkhunis grow and mature, we will be able to do more and more to help our bhikkhu brothers to serve the Sasana. May we all work together to help ever more beings, including ourselves, find liberation from suffering.