If You Honor Me, Honor My Mother Gotami

The Buddha’s Second Mother and First Mother of the Bhikkhunis

by Jacqueline Kramer

From the Winter 2011 edition of Present

Like two stars shining brightly at the auspicious birth of a great presence, the Buddha was blessed with two great mothers, Maya, who offered her body as his final vessel, and Pajapati, who nursed and raised him as her own. The two sisters were born in Devadaha 2600 years ago on the fertile land at the foothills of the Himalayan Mountains. As daughters of the Sakyan royal family, all their earthly needs were well met. The soothsayers foretold that the younger sister would grow up to be a leader of many people so they called her Pajapati, which means leader of an assembly of people. When Maya, the elder sister, came of age, she was sent to the neighboring region of Kapilavastu to be married to King Suddhodana, ruler of the Sakyan people. Twenty-five years into her marriage, Maya, now forty years old, had still not conceived a child. King Suddhodana, needing to produce an heir to the throne, married Maya’s younger sister, Pajapati.

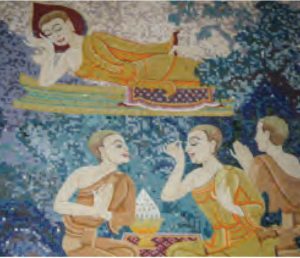

The new marriage worked its magic. Both sisters became pregnant at the same time. Maya was the first to give birth. As was the custom at the time, Maya returned to the home of her father and mother to deliver the baby. While en route to her childhood home, she was drawn to a beautiful park, alive with green trees, scented flowers, wild birds full of songs and busy bees. It was here, on a full moon eve, supported by a sala tree, that Maya released the future Buddha into the world. The baby walked seven steps. At each step a pristine lotus rose out of the rich, brown soil. Mother, son and retinue returned to the palace, to an overjoyed King. The soothsayers named the boy Siddhartha – he who accomplishes his aim. Shortly thereafter, Pajapati gave birth to Nanda. Seven days after the birth of Siddhartha, Maya passed away. Pajapati relinquished her own son to a wet nurse and, as the new first Queen, donned the responsibility of nursing and raising Siddhartha, the young crown prince. Later, she went on to give birth to a daughter named Sundari Nanda. The story of Pajapati then slips into oblivion only to reemerge at the time of the Buddha’s return to Kapilavastu.

What would the Buddha’s narrative look like if it included stories about how Pajapati guided him?

A lion’s share of what we know about the Buddha and his life is in the form of story, lyrical vignettes laced with wisdom in the form of parables about his growing up and eventual enlightenment. There are many teachings sewn into the folds of Siddhartha’s life story, such as the teaching on kindness found in the story about Devadatta and the swan. When Devadatta, Siddhartha’s cousin, shot down a swan with his bow and arrow, the young Siddhartha found the swan in the brush, carefully removed the arrow and nursed the ailing bird back to life. Devadatta claimed that the swan belonged to him because he had shot it down. Siddhartha successfully argued the case before a jury of adults that the swan belongs to him who saves a life, not him who takes a life. In another story, we watch a young Siddhartha spontaneously fall into meditation while sitting under a Rose Apple Tree during the annual spring plowing ceremony. Although there are numerous stories about Siddhartha’s education and training as a young prince, there are no stories about what his father or his mother taught him, no glimpses of intimate moments shared between son and mother. The mother disappears from the story.

Our mother is our first spiritual teacher, a reality that is often overlooked in the stories of many great men, including the Buddha. This is not because of an assertion that Siddhartha emerged perfectly realized from birth. Although the seeds of Siddhartha’s compassion were sown over many lifetimes, he returned to human form because he had further to grow in order to achieve full realization. The Buddha stressed that he was born a man, not a god. We watch him go to excess with self-mortification and bring himself back from the brink of self-inflicted death by way of the middle path. Siddhartha discovers the middle path by going to excess. He is not born with this wisdom. We watch Siddhartha grow and develop throughout his awakening story. Siddhartha’s learning process, and the fact that he is not portrayed as perfectly enlightened from the start, is an important teaching for all the unenlightened. It shows us that with enough wise direction, commitment and fire, we too can become Buddhas, we too can wake up. How did the young Siddhartha develop the high degree of compassion and wisdom necessary to leave the comfort of the luxurious palace and face the unknown in his quest for a path leading out of the thorns and brambles of suffering?

We each know, from our own experiences, how the pains and pleasures of our early life have shaped the passions we carry into our adult life. We all grow up in environments where adults, usually our mothers and/or fathers, influence our character and worldview. If you think about your mother I’m sure you will find at least a few lessons that have led to your character today, whether it is a choice to emulate her actions or to oppose them. When I think about my mother, I remember how she valued impeccability in speech and action. She would not take a penny that did not belong to her and treated the people who worked for her with great respect and kindness. From this I learned about staying true to my values even when no one was looking. I also learned, from my mother’s lack of confidence, the power of internalized disrespect. The disrespect for women I experienced in my family led to a great passion to support and honor women everywhere. The space in my heart carved out by my own pain now can hold the pain of others.

We each know, from our own experiences, how the pains and pleasures of our early life have shaped the passions we carry into our adult life. We all grow up in environments where adults, usually our mothers and/or fathers, influence our character and worldview. If you think about your mother I’m sure you will find at least a few lessons that have led to your character today, whether it is a choice to emulate her actions or to oppose them. When I think about my mother, I remember how she valued impeccability in speech and action. She would not take a penny that did not belong to her and treated the people who worked for her with great respect and kindness. From this I learned about staying true to my values even when no one was looking. I also learned, from my mother’s lack of confidence, the power of internalized disrespect. The disrespect for women I experienced in my family led to a great passion to support and honor women everywhere. The space in my heart carved out by my own pain now can hold the pain of others.

Although the teaching of gratitude towards one’s mother is deep in the Buddhist tradition, as we see in the story of the Buddha ascending to heaven to teach his birth mother the dharma, we are not provided with any intimate moments between Pajapati and Siddhartha as he is developing his character. In Judaism the opportunity to fill in missing pieces of a story is called Midrash. An example of midrash is the story of Abraham smashing idols in his father’s shop though not found in the bible. Yet this story has become common knowledge. What would the Buddha’s narrative look like if it included stories about how Pajapati guided him? We know that great compassion comes from the transformation of great pain. What was the pain young Siddhartha felt that led to his great compassion? How may his foster mother have guided the young boy towards the transformation of his pain into compassion? I would love to listen in as Pajapati instructs and guides this exceptionally bright, receptive child. Did she comfort him with stories of great things coming from small sorrows when he experienced cruelty at the hands of other children? Did she hold him when he cried, did she help him understand that the biting words and deeds of others are born from their own sorrow, that their words and deeds are an expression of what is left unhealed in their hearts, that unkindness can never diminish that which continues to shine brightly within both the giver and the receiver, that what unkindness calls for is not retaliation but love? The powerful moments between a mother, or father, and child are often simple moments. Because the teachings that lead to deep habits are usually repetitive rather than dramatic and spoken in whispers rather than shouted, they often go unacknowledged. What if we could reclaim some of those missing moments in the Buddha story?

Gotami’s tenacity is a wonderful model of a consciousness ready to put everything on the line for enlightenment.

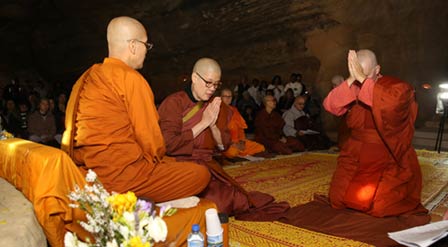

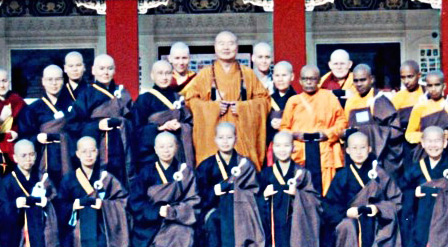

Seven years after Siddhartha left home to seek the end of suffering for all beings, he returned to the palace gates of his childhood, thirty-five years old and having found what he had sought. He left as Siddhartha and returned a Buddha. Pajapati, now in her seventies, re-enters the Buddha’s story. After hearing, seeing and feeling the transformed presence of the boy she had raised, both Pajapati and her husband are so deeply moved by their son’s teachings they become his students. One by one, the men in Gotami’s life decide to follow the esteemed teacher. Her son Nanda and her grandson Rahula both leave the palace to join the monastic sangha. Shortly thereafter her husband dies leaving Pajapati as Head of State. It was not an easy time for her. There was a major dispute over water rights between the Sakyans and their neighbors and the best and brightest of the tribe were abandoning leadership roles to join the Buddha’s sangha. As more and more men left to follow the Buddha, many of the women came to the great woman of the Gotama clan, Gotami, now a stream enterer, for spiritual support and advice. Five hundred women, a number signifying a large amount, urged Gotami to petition the Buddha to allow women to join the monastic sangha.

The story most of us have heard, the story passed down about how Gotami becomes the first bhikkhuni, typically begins with her begging the Buddha to let her, and 500 other women from his former life, join the sangha. The story shows Gotami following an all-male sangha barefoot, coming to Ananda in tears, entreating him to plead her case to the Buddha, to allow women to join the sangha and, basically, not taking no for an answer. This story about asking three times has been interpreted as a reflection of the Buddha’s disregard for women. But we can glean a deeper meaning to the story about asking three times. In the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, Mara, the tempter, challenges the Buddha soon after his enlightenment by insinuating that his time to pass away has come. The Buddha proclaims that, “I will not pass away until I have bhikkhuni disciples who are wise, well-trained, self-confident and learned.” We need to ask, if the old texts show the Buddha making such a strong commitment to include women in his sangha directly after his enlightenment, why would he hesitate to allow women to become bhikkhunis when asked by his beloved foster mother?

Asking three times shows up again and again, both in Buddhism and in other cultures. I am reminded here of how Rabbis will not take a non-Jew as an applicant for conversion until they have asked for this training a number of times. This form of testing an applicant’s resolve is not limited to Buddhism and, in Buddhism, is not limited to the inclusion of Gotami into the sangha. When the Buddha was in Rajagaha, he came upon the naked ascetic Kassapa who said, “If the honorable Gotama would permit me, if he would give me an opportunity to hear his answer, I would like to question him about a certain matter.” Kassapa had to ask for this audience three times before the Buddha said, “You may ask whatever you like.” Three appears to be a number signifying resolve. The Buddha believed in the value of tenacious adherence to a good cause, as have many spiritual teachers before and after him. To this day ordination procedures have three-fold repetitions, as does recitation of the three refuges. In vipassana practice we are taught to repeat the name of whatever sense the mind alights on three times, such as “seeing, seeing, seeing” or “hearing, hearing, hearing,” in order to let the awareness set in. It takes firm resolve, also known as right effort, to walk the spiritual path through all the ups and downs, year after year. Gotami’s tenacity is a wonderful model of a consciousness ready to put everything on the line for enlightenment.

Asking three times shows up again and again, both in Buddhism and in other cultures. I am reminded here of how Rabbis will not take a non-Jew as an applicant for conversion until they have asked for this training a number of times. This form of testing an applicant’s resolve is not limited to Buddhism and, in Buddhism, is not limited to the inclusion of Gotami into the sangha. When the Buddha was in Rajagaha, he came upon the naked ascetic Kassapa who said, “If the honorable Gotama would permit me, if he would give me an opportunity to hear his answer, I would like to question him about a certain matter.” Kassapa had to ask for this audience three times before the Buddha said, “You may ask whatever you like.” Three appears to be a number signifying resolve. The Buddha believed in the value of tenacious adherence to a good cause, as have many spiritual teachers before and after him. To this day ordination procedures have three-fold repetitions, as does recitation of the three refuges. In vipassana practice we are taught to repeat the name of whatever sense the mind alights on three times, such as “seeing, seeing, seeing” or “hearing, hearing, hearing,” in order to let the awareness set in. It takes firm resolve, also known as right effort, to walk the spiritual path through all the ups and downs, year after year. Gotami’s tenacity is a wonderful model of a consciousness ready to put everything on the line for enlightenment.

But, the time was not yet right to bring so many women into the newly forming sangha. There were many real and practical concerns that the Buddha faced while setting up his new monastic order. If he did not firmly establish the male sangha first, he may not have had enough support from the laity to physically maintain the two sanghas. The laity might have questioned the integrity of a sangha where men and women lived together or where women lived independently. Even though there were already female wandering ascetics at the time and an existing Jain bhikkhuni order, ordaining women in great numbers could be problematic. Also, some scholars have noted the problem of timing in the story of Gotami asking Ananda to intercede and petition the Buddha on her behalf. Research shows that Ananda would not become the Buddha’s attendant until fifteen years after Gotami’s ordination. Many scholars even question whether Gotami was the first bhikkhuni. The history is unresolved here. There is the possibility that Bhadda Kundalakesa was the first bhikkhuni. Also, there is some evidence that an early group of bhikkhunis may already have been living at Vulture Peak. But Gotami was the first to come to him with such enormous numbers of female aspirants. Perhaps the story of Gotami’s ordination, making her the mother of bhikkhunis, could have been as simple as the Buddha, gazing lovingly at the woman who cared and nurtured him, extends his hand in gratitude and gives his beloved foster mother the most valuable gift he could possibly give, the gift of the dhamma. It is beautiful to think about this ordination as a simple exchange of precious gifts, one heart to another. However the initiation came about, whether the Buddha ordained Gotami with a simple gesture of his hand and the words “Come nun” or in some other fashion, the Buddha’s second mother became foremost in seniority amongst the Buddha’s bhikkhuni disciples.

I nursed you with mother’s milk

Which quenched your thirst for a moment.

From you I drank the dharma-milk

And am now forever sated.

You do not owe any debt to me

For raising and nurturing you.

Great sage, to have had you as a son,

Quenches all my desires.

The Buddha was deeply respectful of women. He likened his teachings on loving kindness to the way a mother loves her only child, and encouraged us to extend this love to all beings. He pushed the envelope as far as he could, given the social situation at the time. So how did misogyny creep into such enlightened teachings? Some of the Buddhist teachings regarding women that have been passed down are not necessarily the work of truly enlightened minds. As with all organized religions, there are both enlightened and unenlightened among the ranks. It is a common phenomenon throughout history for those who have the power to use stories to cause others to conform to their viewpoint. The victors write the history and the victors are not always the most enlightened within the ranks. In this respect, Buddhism is no different from other large organized institutions. This is why it is so important to look deeply into what an enlightened mind, the Buddha mind, sees rather than blindly stick to the stories as they are passed down. In sorting this all out, we are well advised to look at the moon rather than the finger pointing to the moon.

If we remember that most of what has been passed down about the Buddha is in the form of story, rather than history, we can be thoughtful about what lessons we choose to keep and which to let go. We can ask the question, does this teaching conform to the enlightened mind of a Buddha? And if it does not, we can release it.

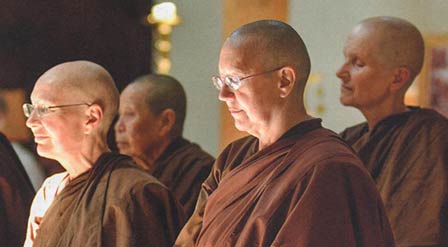

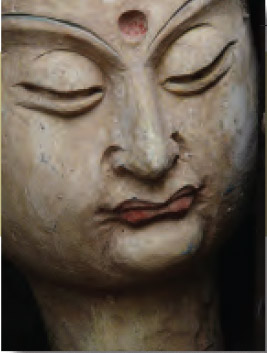

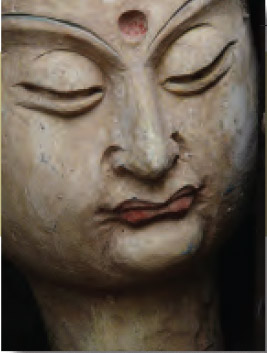

In the age-old tradition of story-telling, the stories that stay alive the longest are the ones that have the flexibility to change and morph yet retain their essential meaning in response to changing times and new cultures. There is already precedent of the Buddha’s story changing as it enters a new culture. An example of this is how the Buddha of compassion, Avalokitesvara, changed from a male deity to a female deity when Buddhism moved to China. The Chinese see compassion as a female quality so in order to transmit the teaching of compassion to the Chinese people the heavenly teacher became a goddess. As Buddhism now moves West, perhaps we can leave behind the traces of other cultures that view women as second-class citizens and import the vision of an enlightened mind which has women sitting side by side with men, not better and not worse. I think this was the Buddha’s original vision as is evidenced by his telling Mara directly after his enlightenment that he would not pass away until there were wise, enlightened bhikkhunis. Through this he made clear that both men and women are capable of attaining the enlightened state.

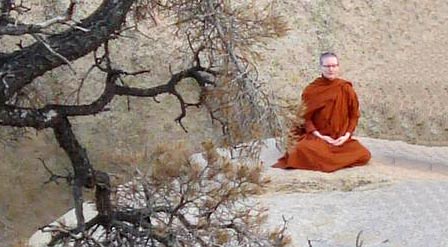

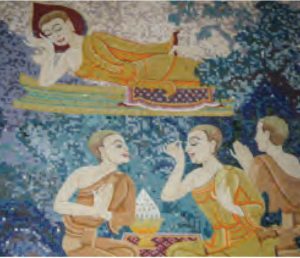

After her ordination, Mahapajapati received a meditation subject and, through her reflection on it, realized the state of perfection saying, “I have reached the state where everything stops.” She continued on as an elder and teacher until the ripe old age of one hundred and twenty. When her time of death was drawing near, she requested to see her son one last time. Although it was against monastic regulation for a bhikkhu to visit a bhikkhuni this way, her wish was granted when the Buddha came to visit her on her deathbed. Her final words to the Buddha were, “I nursed you with mother’s milk, which quenched your thirst for a moment. For you I drank the dharma-milk and am now forever sated. You do not owe any debt to me for raising and nurturing you. Great sage, to have had a son, quenches all my desires.”

Gotami then put her head down on the Buddha’s feet, feet that emitted the fragrance of lotuses in bloom. Upon his soles were marks in the form of radiating wheels like a young sun’s shining rays. Realizing that there were foolish people who would doubt that women could attain full enlightenment, the Buddha asked Gotami to perform many miracles to show the capabilities of a woman arahant. She bowed to the Buddha, then leapt into the sky. Having been one she became many, having been many she became one. She sank down deep into the Earth and walked over the water without breaking the surface. Sitting cross-legged she flew like a bird across the sky. She held great mountains as if they were tiny mustard seeds and finally, extinguished in a flash, like the flame in a lamp that has no more fuel.

Gotami then put her head down on the Buddha’s feet, feet that emitted the fragrance of lotuses in bloom. Upon his soles were marks in the form of radiating wheels like a young sun’s shining rays. Realizing that there were foolish people who would doubt that women could attain full enlightenment, the Buddha asked Gotami to perform many miracles to show the capabilities of a woman arahant. She bowed to the Buddha, then leapt into the sky. Having been one she became many, having been many she became one. She sank down deep into the Earth and walked over the water without breaking the surface. Sitting cross-legged she flew like a bird across the sky. She held great mountains as if they were tiny mustard seeds and finally, extinguished in a flash, like the flame in a lamp that has no more fuel.

The Buddha declared, “Now go Ananda, tell the monks my mother has reached nirvana. Dear Gotami, she who carefully raised me when I was helpless has gone to a deep peace, just like the stars at sunrise. If you honor me, honor my mother Gotami. Know this, she was most wise, with wisdom vast and wide.” When the Buddha had thus honored his mother, the gods offered garlands scented with divine perfume and worshiped Gotami with song, music, and dance.

References:

Therī-Apadāna (Lives of Senior Nuns, Khuddaka Nikāya 11 [CST, DPR] or 13 [PTS, BPS]), Translations by Ajahn Maha Prasert Kavissaro (Phra Chaokhun Vitesdhammakavi), Tathaaloka Theri, William Pruitt (see below), Jonathan Walters, and Dr. Ranjini Obeysekere.

Horner, I. B., Women Under Primitive Buddhism – Laywomen and Almswomen, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1990 (First Edition: London, 1930).

Mohr, Thea, and Jampa Tsedroen, Bhikṣuṇī, eds., Dignity and Discipline – Reviving Full Ordination for Buddhist Nuns, Somerville: Wisdom Publications, 2010.

Murcott, Susan, First Buddhist Women – Translations and Commentary on the Therigatha, Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1991.

Paul, Diana Y., Women in Buddhism – Images of the Feminine in the Mahāyāna Tradition, Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press, 1979.

Piyadassi Thera, The Virgin’s Eye: Women in Buddhist Literature, Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1980.

Pruitt, William, trans., The Commentary on the Verses of the Therīs, Oxford: 1998, Pali Text Society (includes translations of twenty-five of the forty Therī-Apadāna; available from Wisdom Books).

Wijayaratna, Mohan, Buddhist Nuns – The Birth and Development of a Women’s Monastic Order, Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 2001.

About the Author

Jacqueline Kramer, author of Buddha Mom – the Path of Mindful Mothering, has been studying and practicing Buddhism for over 36 years. Her root teachings are in the Sri Lankan Theravadin tradition and she is now studying Zen koans. She is the director of Hearth Foundation which offers classes and support for parents who wish to awaken at home. The website is www.hearth-foundation.org

For the last few years, she has been focusing on painting and has created a Syrian refugee art project which helps to create fundraisers for the Syrian refugees through the International Rescue Committee. See her work at http://jacquelinekramer.work/

From the Winter 2011 edition of Present

Like two stars shining brightly at the auspicious birth of a great presence, the Buddha was blessed with two great mothers, Maya, who offered her body as his final vessel, and Pajapati, who nursed and raised him as her own. The two sisters were born in Devadaha 2600 years ago on the fertile land at the foothills of the Himalayan Mountains. As daughters of the Sakyan royal family, all their earthly needs were well met. The soothsayers foretold that the younger sister would grow up to be a leader of many people so they called her Pajapati, which means leader of an assembly of people. When Maya, the elder sister, came of age, she was sent to the neighboring region of Kapilavastu to be married to King Suddhodana, ruler of the Sakyan people. Twenty-five years into her marriage, Maya, now forty years old, had still not conceived a child. King Suddhodana, needing to produce an heir to the throne, married Maya’s younger sister, Pajapati.

The new marriage worked its magic. Both sisters became pregnant at the same time. Maya was the first to give birth. As was the custom at the time, Maya returned to the home of her father and mother to deliver the baby. While en route to her childhood home, she was drawn to a beautiful park, alive with green trees, scented flowers, wild birds full of songs and busy bees. It was here, on a full moon eve, supported by a sala tree, that Maya released the future Buddha into the world. The baby walked seven steps. At each step a pristine lotus rose out of the rich, brown soil. Mother, son and retinue returned to the palace, to an overjoyed King. The soothsayers named the boy Siddhartha – he who accomplishes his aim. Shortly thereafter, Pajapati gave birth to Nanda. Seven days after the birth of Siddhartha, Maya passed away. Pajapati relinquished her own son to a wet nurse and, as the new first Queen, donned the responsibility of nursing and raising Siddhartha, the young crown prince. Later, she went on to give birth to a daughter named Sundari Nanda. The story of Pajapati then slips into oblivion only to reemerge at the time of the Buddha’s return to Kapilavastu.

What would the Buddha’s narrative look like if it included stories about how Pajapati guided him?

A lion’s share of what we know about the Buddha and his life is in the form of story, lyrical vignettes laced with wisdom in the form of parables about his growing up and eventual enlightenment. There are many teachings sewn into the folds of Siddhartha’s life story, such as the teaching on kindness found in the story about Devadatta and the swan. When Devadatta, Siddhartha’s cousin, shot down a swan with his bow and arrow, the young Siddhartha found the swan in the brush, carefully removed the arrow and nursed the ailing bird back to life. Devadatta claimed that the swan belonged to him because he had shot it down. Siddhartha successfully argued the case before a jury of adults that the swan belongs to him who saves a life, not him who takes a life. In another story, we watch a young Siddhartha spontaneously fall into meditation while sitting under a Rose Apple Tree during the annual spring plowing ceremony. Although there are numerous stories about Siddhartha’s education and training as a young prince, there are no stories about what his father or his mother taught him, no glimpses of intimate moments shared between son and mother. The mother disappears from the story.

Our mother is our first spiritual teacher, a reality that is often overlooked in the stories of many great men, including the Buddha. This is not because of an assertion that Siddhartha emerged perfectly realized from birth. Although the seeds of Siddhartha’s compassion were sown over many lifetimes, he returned to human form because he had further to grow in order to achieve full realization. The Buddha stressed that he was born a man, not a god. We watch him go to excess with self-mortification and bring himself back from the brink of self-inflicted death by way of the middle path. Siddhartha discovers the middle path by going to excess. He is not born with this wisdom. We watch Siddhartha grow and develop throughout his awakening story. Siddhartha’s learning process, and the fact that he is not portrayed as perfectly enlightened from the start, is an important teaching for all the unenlightened. It shows us that with enough wise direction, commitment and fire, we too can become Buddhas, we too can wake up. How did the young Siddhartha develop the high degree of compassion and wisdom necessary to leave the comfort of the luxurious palace and face the unknown in his quest for a path leading out of the thorns and brambles of suffering?

We each know, from our own experiences, how the pains and pleasures of our early life have shaped the passions we carry into our adult life. We all grow up in environments where adults, usually our mothers and/or fathers, influence our character and worldview. If you think about your mother I’m sure you will find at least a few lessons that have led to your character today, whether it is a choice to emulate her actions or to oppose them. When I think about my mother, I remember how she valued impeccability in speech and action. She would not take a penny that did not belong to her and treated the people who worked for her with great respect and kindness. From this I learned about staying true to my values even when no one was looking. I also learned, from my mother’s lack of confidence, the power of internalized disrespect. The disrespect for women I experienced in my family led to a great passion to support and honor women everywhere. The space in my heart carved out by my own pain now can hold the pain of others.

We each know, from our own experiences, how the pains and pleasures of our early life have shaped the passions we carry into our adult life. We all grow up in environments where adults, usually our mothers and/or fathers, influence our character and worldview. If you think about your mother I’m sure you will find at least a few lessons that have led to your character today, whether it is a choice to emulate her actions or to oppose them. When I think about my mother, I remember how she valued impeccability in speech and action. She would not take a penny that did not belong to her and treated the people who worked for her with great respect and kindness. From this I learned about staying true to my values even when no one was looking. I also learned, from my mother’s lack of confidence, the power of internalized disrespect. The disrespect for women I experienced in my family led to a great passion to support and honor women everywhere. The space in my heart carved out by my own pain now can hold the pain of others.

Although the teaching of gratitude towards one’s mother is deep in the Buddhist tradition, as we see in the story of the Buddha ascending to heaven to teach his birth mother the dharma, we are not provided with any intimate moments between Pajapati and Siddhartha as he is developing his character. In Judaism the opportunity to fill in missing pieces of a story is called Midrash. An example of midrash is the story of Abraham smashing idols in his father’s shop though not found in the bible. Yet this story has become common knowledge. What would the Buddha’s narrative look like if it included stories about how Pajapati guided him? We know that great compassion comes from the transformation of great pain. What was the pain young Siddhartha felt that led to his great compassion? How may his foster mother have guided the young boy towards the transformation of his pain into compassion? I would love to listen in as Pajapati instructs and guides this exceptionally bright, receptive child. Did she comfort him with stories of great things coming from small sorrows when he experienced cruelty at the hands of other children? Did she hold him when he cried, did she help him understand that the biting words and deeds of others are born from their own sorrow, that their words and deeds are an expression of what is left unhealed in their hearts, that unkindness can never diminish that which continues to shine brightly within both the giver and the receiver, that what unkindness calls for is not retaliation but love? The powerful moments between a mother, or father, and child are often simple moments. Because the teachings that lead to deep habits are usually repetitive rather than dramatic and spoken in whispers rather than shouted, they often go unacknowledged. What if we could reclaim some of those missing moments in the Buddha story?

Gotami’s tenacity is a wonderful model of a consciousness ready to put everything on the line for enlightenment.

Seven years after Siddhartha left home to seek the end of suffering for all beings, he returned to the palace gates of his childhood, thirty-five years old and having found what he had sought. He left as Siddhartha and returned a Buddha. Pajapati, now in her seventies, re-enters the Buddha’s story. After hearing, seeing and feeling the transformed presence of the boy she had raised, both Pajapati and her husband are so deeply moved by their son’s teachings they become his students. One by one, the men in Gotami’s life decide to follow the esteemed teacher. Her son Nanda and her grandson Rahula both leave the palace to join the monastic sangha. Shortly thereafter her husband dies leaving Pajapati as Head of State. It was not an easy time for her. There was a major dispute over water rights between the Sakyans and their neighbors and the best and brightest of the tribe were abandoning leadership roles to join the Buddha’s sangha. As more and more men left to follow the Buddha, many of the women came to the great woman of the Gotama clan, Gotami, now a stream enterer, for spiritual support and advice. Five hundred women, a number signifying a large amount, urged Gotami to petition the Buddha to allow women to join the monastic sangha.

The story most of us have heard, the story passed down about how Gotami becomes the first bhikkhuni, typically begins with her begging the Buddha to let her, and 500 other women from his former life, join the sangha. The story shows Gotami following an all-male sangha barefoot, coming to Ananda in tears, entreating him to plead her case to the Buddha, to allow women to join the sangha and, basically, not taking no for an answer. This story about asking three times has been interpreted as a reflection of the Buddha’s disregard for women. But we can glean a deeper meaning to the story about asking three times. In the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, Mara, the tempter, challenges the Buddha soon after his enlightenment by insinuating that his time to pass away has come. The Buddha proclaims that, “I will not pass away until I have bhikkhuni disciples who are wise, well-trained, self-confident and learned.” We need to ask, if the old texts show the Buddha making such a strong commitment to include women in his sangha directly after his enlightenment, why would he hesitate to allow women to become bhikkhunis when asked by his beloved foster mother?

Asking three times shows up again and again, both in Buddhism and in other cultures. I am reminded here of how Rabbis will not take a non-Jew as an applicant for conversion until they have asked for this training a number of times. This form of testing an applicant’s resolve is not limited to Buddhism and, in Buddhism, is not limited to the inclusion of Gotami into the sangha. When the Buddha was in Rajagaha, he came upon the naked ascetic Kassapa who said, “If the honorable Gotama would permit me, if he would give me an opportunity to hear his answer, I would like to question him about a certain matter.” Kassapa had to ask for this audience three times before the Buddha said, “You may ask whatever you like.” Three appears to be a number signifying resolve. The Buddha believed in the value of tenacious adherence to a good cause, as have many spiritual teachers before and after him. To this day ordination procedures have three-fold repetitions, as does recitation of the three refuges. In vipassana practice we are taught to repeat the name of whatever sense the mind alights on three times, such as “seeing, seeing, seeing” or “hearing, hearing, hearing,” in order to let the awareness set in. It takes firm resolve, also known as right effort, to walk the spiritual path through all the ups and downs, year after year. Gotami’s tenacity is a wonderful model of a consciousness ready to put everything on the line for enlightenment.

Asking three times shows up again and again, both in Buddhism and in other cultures. I am reminded here of how Rabbis will not take a non-Jew as an applicant for conversion until they have asked for this training a number of times. This form of testing an applicant’s resolve is not limited to Buddhism and, in Buddhism, is not limited to the inclusion of Gotami into the sangha. When the Buddha was in Rajagaha, he came upon the naked ascetic Kassapa who said, “If the honorable Gotama would permit me, if he would give me an opportunity to hear his answer, I would like to question him about a certain matter.” Kassapa had to ask for this audience three times before the Buddha said, “You may ask whatever you like.” Three appears to be a number signifying resolve. The Buddha believed in the value of tenacious adherence to a good cause, as have many spiritual teachers before and after him. To this day ordination procedures have three-fold repetitions, as does recitation of the three refuges. In vipassana practice we are taught to repeat the name of whatever sense the mind alights on three times, such as “seeing, seeing, seeing” or “hearing, hearing, hearing,” in order to let the awareness set in. It takes firm resolve, also known as right effort, to walk the spiritual path through all the ups and downs, year after year. Gotami’s tenacity is a wonderful model of a consciousness ready to put everything on the line for enlightenment.

But, the time was not yet right to bring so many women into the newly forming sangha. There were many real and practical concerns that the Buddha faced while setting up his new monastic order. If he did not firmly establish the male sangha first, he may not have had enough support from the laity to physically maintain the two sanghas. The laity might have questioned the integrity of a sangha where men and women lived together or where women lived independently. Even though there were already female wandering ascetics at the time and an existing Jain bhikkhuni order, ordaining women in great numbers could be problematic. Also, some scholars have noted the problem of timing in the story of Gotami asking Ananda to intercede and petition the Buddha on her behalf. Research shows that Ananda would not become the Buddha’s attendant until fifteen years after Gotami’s ordination. Many scholars even question whether Gotami was the first bhikkhuni. The history is unresolved here. There is the possibility that Bhadda Kundalakesa was the first bhikkhuni. Also, there is some evidence that an early group of bhikkhunis may already have been living at Vulture Peak. But Gotami was the first to come to him with such enormous numbers of female aspirants. Perhaps the story of Gotami’s ordination, making her the mother of bhikkhunis, could have been as simple as the Buddha, gazing lovingly at the woman who cared and nurtured him, extends his hand in gratitude and gives his beloved foster mother the most valuable gift he could possibly give, the gift of the dhamma. It is beautiful to think about this ordination as a simple exchange of precious gifts, one heart to another. However the initiation came about, whether the Buddha ordained Gotami with a simple gesture of his hand and the words “Come nun” or in some other fashion, the Buddha’s second mother became foremost in seniority amongst the Buddha’s bhikkhuni disciples.

I nursed you with mother’s milk

Which quenched your thirst for a moment.

From you I drank the dharma-milk

And am now forever sated.

You do not owe any debt to me

For raising and nurturing you.

Great sage, to have had you as a son,

Quenches all my desires.

The Buddha was deeply respectful of women. He likened his teachings on loving kindness to the way a mother loves her only child, and encouraged us to extend this love to all beings. He pushed the envelope as far as he could, given the social situation at the time. So how did misogyny creep into such enlightened teachings? Some of the Buddhist teachings regarding women that have been passed down are not necessarily the work of truly enlightened minds. As with all organized religions, there are both enlightened and unenlightened among the ranks. It is a common phenomenon throughout history for those who have the power to use stories to cause others to conform to their viewpoint. The victors write the history and the victors are not always the most enlightened within the ranks. In this respect, Buddhism is no different from other large organized institutions. This is why it is so important to look deeply into what an enlightened mind, the Buddha mind, sees rather than blindly stick to the stories as they are passed down. In sorting this all out, we are well advised to look at the moon rather than the finger pointing to the moon.

If we remember that most of what has been passed down about the Buddha is in the form of story, rather than history, we can be thoughtful about what lessons we choose to keep and which to let go. We can ask the question, does this teaching conform to the enlightened mind of a Buddha? And if it does not, we can release it.

In the age-old tradition of story-telling, the stories that stay alive the longest are the ones that have the flexibility to change and morph yet retain their essential meaning in response to changing times and new cultures. There is already precedent of the Buddha’s story changing as it enters a new culture. An example of this is how the Buddha of compassion, Avalokitesvara, changed from a male deity to a female deity when Buddhism moved to China. The Chinese see compassion as a female quality so in order to transmit the teaching of compassion to the Chinese people the heavenly teacher became a goddess. As Buddhism now moves West, perhaps we can leave behind the traces of other cultures that view women as second-class citizens and import the vision of an enlightened mind which has women sitting side by side with men, not better and not worse. I think this was the Buddha’s original vision as is evidenced by his telling Mara directly after his enlightenment that he would not pass away until there were wise, enlightened bhikkhunis. Through this he made clear that both men and women are capable of attaining the enlightened state.

After her ordination, Mahapajapati received a meditation subject and, through her reflection on it, realized the state of perfection saying, “I have reached the state where everything stops.” She continued on as an elder and teacher until the ripe old age of one hundred and twenty. When her time of death was drawing near, she requested to see her son one last time. Although it was against monastic regulation for a bhikkhu to visit a bhikkhuni this way, her wish was granted when the Buddha came to visit her on her deathbed. Her final words to the Buddha were, “I nursed you with mother’s milk, which quenched your thirst for a moment. For you I drank the dharma-milk and am now forever sated. You do not owe any debt to me for raising and nurturing you. Great sage, to have had a son, quenches all my desires.”

Gotami then put her head down on the Buddha’s feet, feet that emitted the fragrance of lotuses in bloom. Upon his soles were marks in the form of radiating wheels like a young sun’s shining rays. Realizing that there were foolish people who would doubt that women could attain full enlightenment, the Buddha asked Gotami to perform many miracles to show the capabilities of a woman arahant. She bowed to the Buddha, then leapt into the sky. Having been one she became many, having been many she became one. She sank down deep into the Earth and walked over the water without breaking the surface. Sitting cross-legged she flew like a bird across the sky. She held great mountains as if they were tiny mustard seeds and finally, extinguished in a flash, like the flame in a lamp that has no more fuel.

Gotami then put her head down on the Buddha’s feet, feet that emitted the fragrance of lotuses in bloom. Upon his soles were marks in the form of radiating wheels like a young sun’s shining rays. Realizing that there were foolish people who would doubt that women could attain full enlightenment, the Buddha asked Gotami to perform many miracles to show the capabilities of a woman arahant. She bowed to the Buddha, then leapt into the sky. Having been one she became many, having been many she became one. She sank down deep into the Earth and walked over the water without breaking the surface. Sitting cross-legged she flew like a bird across the sky. She held great mountains as if they were tiny mustard seeds and finally, extinguished in a flash, like the flame in a lamp that has no more fuel.

The Buddha declared, “Now go Ananda, tell the monks my mother has reached nirvana. Dear Gotami, she who carefully raised me when I was helpless has gone to a deep peace, just like the stars at sunrise. If you honor me, honor my mother Gotami. Know this, she was most wise, with wisdom vast and wide.” When the Buddha had thus honored his mother, the gods offered garlands scented with divine perfume and worshiped Gotami with song, music, and dance.

References:

Therī-Apadāna (Lives of Senior Nuns, Khuddaka Nikāya 11 [CST, DPR] or 13 [PTS, BPS]), Translations by Ajahn Maha Prasert Kavissaro (Phra Chaokhun Vitesdhammakavi), Tathaaloka Theri, William Pruitt (see below), Jonathan Walters, and Dr. Ranjini Obeysekere.

Horner, I. B., Women Under Primitive Buddhism – Laywomen and Almswomen, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1990 (First Edition: London, 1930).

Mohr, Thea, and Jampa Tsedroen, Bhikṣuṇī, eds., Dignity and Discipline – Reviving Full Ordination for Buddhist Nuns, Somerville: Wisdom Publications, 2010.

Murcott, Susan, First Buddhist Women – Translations and Commentary on the Therigatha, Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1991.

Paul, Diana Y., Women in Buddhism – Images of the Feminine in the Mahāyāna Tradition, Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press, 1979.

Piyadassi Thera, The Virgin’s Eye: Women in Buddhist Literature, Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1980.

Pruitt, William, trans., The Commentary on the Verses of the Therīs, Oxford: 1998, Pali Text Society (includes translations of twenty-five of the forty Therī-Apadāna; available from Wisdom Books).

Wijayaratna, Mohan, Buddhist Nuns – The Birth and Development of a Women’s Monastic Order, Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 2001.

About the Author

Jacqueline Kramer, author of Buddha Mom – the Path of Mindful Mothering, has been studying and practicing Buddhism for over 36 years. Her root teachings are in the Sri Lankan Theravadin tradition and she is now studying Zen koans. She is the director of Hearth Foundation which offers classes and support for parents who wish to awaken at home. The website is www.hearth-foundation.org

For the last few years, she has been focusing on painting and has created a Syrian refugee art project which helps to create fundraisers for the Syrian refugees through the International Rescue Committee. See her work at http://jacquelinekramer.work/