Going Forth – for Liberation

by Ajahn Candasirī

Going Forth – for Liberation

by Ajahn Candasirī

Sister Candasirī was born in Scotland. She was one of the first group of nuns to be ordained by Ajahn Sumedho – who was the first Western disciple of the deeply respected Thai master, Venerable Ajahn Chah – at Chithurst Forest Monastery. She took the Eight Precepts as an anagārikā in 1979 and the Ten Precepts, going forth as a sīladhara in 1983. Since then, and until 2012 she lived at either Chithurst or Amaravati Buddhist Monasteries. Now she is living in Perthshire in Scotland where a small hermitage for nuns of her community is being established.

I never, ever, imagined that I would be a nun – of any tradition – even though the experience I had had of monastic life on a couple of retreats in Christian monasteries, though difficult, had seemed utterly fulfilling. I loved the fact that it enabled a whole-hearted commitment to Truth: to realising it and living it out in daily life; and the opportunity to live in a community of people with a similar aspiration. I saw too that there were wider benefits in that people living in such a way can exemplify wholesome qualities that are so needed in our present day society.

I never, ever, imagined that I would be a nun – of any tradition – even though the experience I had had of monastic life on a couple of retreats in Christian monasteries, though difficult, had seemed utterly fulfilling. I loved the fact that it enabled a whole-hearted commitment to Truth: to realising it and living it out in daily life; and the opportunity to live in a community of people with a similar aspiration. I saw too that there were wider benefits in that people living in such a way can exemplify wholesome qualities that are so needed in our present day society.

This, still, is my passion.

It was attending a ten-day retreat over the new year time in 1978/9, led by Ajahn Sumedho at Oakenholt Buddhist Centre near Oxford, that both awakened and confirmed my interest in making a monastic commitment. This was a movement of the heart; the head, the rational mind was profoundly surprised. ‘I’m going to be a Buddhist nun!’ were the words of amazement that would arise in consciousness as I went about my daily life in Edinburgh.

People would ask me what was most difficult to give up when I became a nun. The answer – to the surprise of some – is: ‘Having my own way.’ I had entered the monastic community drawn by a conviction that there is nothing, other than the liberation of the heart, that is worth pursuing. What I was not prepared for was the reality of spiritual companions who, although having a similar aspiration, seemed in every other way to be at odds with my own background personality.

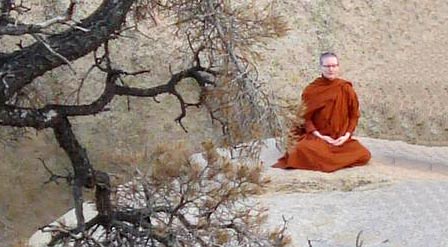

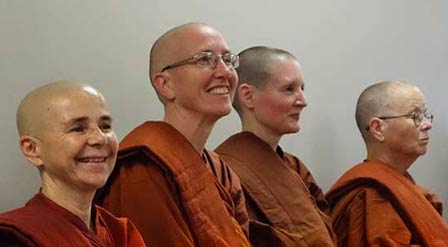

Sisters Sundara, Candasiri, and Rocana

I didn’t particularly want to be a nun living in a community of other nuns. The ego personality was profoundly affected when it became clear that this was what, in effect, I had committed myself to. For the first months, although the four of us were clearly some sort of a group as we worked and meditated alongside the monks at Chithurst, I still managed to feel special. Over time, this changed. There was pressure to conform: to bow and chant together, to be part of a community of nuns. This may seem like a small thing but, for me, it was a huge turning point on the journey of letting go… especially, of the need to be different.

I had always known, theoretically, that as women we would be ‘junior’ to members of the male monastic community. During the early years, the sense of gratitude, devotion and respect that I had for Ajahn Sumedho and the other bhikkhus made the expected outward expression of deference easy and natural – even though it was the opposite of what was expected in the culture I had grown up in and in which we were living. One time at Chithurst, one of a group of Anglican priests who were visiting commented to Ajahn Sumedho his sense of outrage at seeing us on our knees serving him orange juice! Whereas for me, this had become completely normal – a pleasure to be able to serve my teacher in that way.

We served a lot in those days. Everyone worked hard and served in their own way; the monks with many hours each day of heavy building work – there was very little money to pay for the extensive renovation work needed to make the house at Chithurst into a suitable monastic dwelling. As nuns, we cooked, helped with driving, book-keeping and correspondence, and helped to bring the gardens to a state of semi-order. That’s what we did… and, importantly, I felt I belonged.

For me, the move to Amaravati in 1984 represented a major shift. It had been decided that all of the nuns would move to the newly purchased site in Hertfordshire as, by that time our cottage, outbuildings and nearby kutis simply couldn’t accommodate all of us nuns and our guests. Chithurst would be the main training monastery for the monks and, accordingly, kept as a quieter and more secluded residence.

The nuns’ community walked in relays, making the journey as a pilgrimage to our new training monastery. We arrived 2nd August, 1984. A rainbow appeared as we circumambulated the field and made our way into one of the recently vacated huts where a shrine had been created. There, we joined with Ajahn Sumedho, Ajahn Sucitto – who was now, officially, responsible for our training – and the other monks and anagarikas in chanting ‘Jayanto’ – the Buddha’s victory chant.

‘Nuns’ training monastery’, ‘retreat centre’, ‘interfaith library and conference centre’, ‘site for Buddhist festivals and family activities’ and, perhaps, even ‘a crematorium’ – were among the ideas that comprised the initial vision for the place. First of all, though, a substantial debt – together with an urgent need to repair 600 rotting window frames and insulate the large wooden huts – ensured that the whole community quickly acquired new skills and put them to use. I enjoyed the work and, once again, felt happy to be part of something bigger. Ajahn Sumedho had a charisma that inspired and drew everyone together; Ajahn Sucitto met with our nuns’ community regularly to guide us in the basics of monastic training.

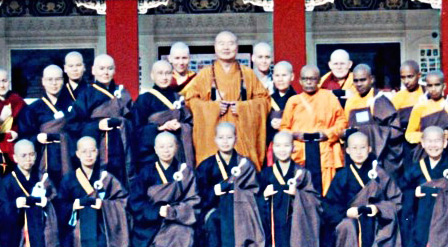

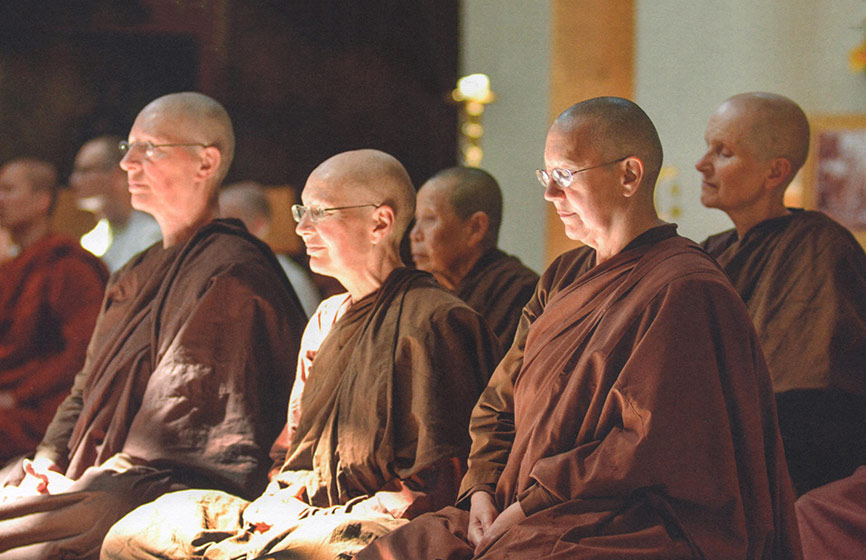

Nuns and Ajahn Sumedho

However, it didn’t take very long for the disparity between the positions of the monks and nuns, that was such an unquestioned aspect of Sangha life in Thailand, to become apparent. This was particularly the case for some of the Western visitors who, even then, in the mid 1980’s, were keenly sensitive to any sense of inequality. I could see that this was challenging for Ajahn Sumedho who really wanted us to focus on our practice for liberation, rather than be distracted by concerns regarding the relative status of others. He began to use the community breakfast times of morning reflection to remind us all of these basic principles of practice – sometimes speaking quite strongly. I was dispirited by the tone of his address – even although I found it inspiring and agreed with what he said.

While living as a lay person, my gender was integral to my way of being – to the extent that it wasn’t something that I thought about very much. However, strangely, when I entered the sangha it assumed a vital importance in terms of all my relationships. While I loved to be serving, giving myself to something that offers such a remarkable structure, way of practice and teaching, there was also a sense of sorrow that, as a nun, I could never be fully included. The monks’ ordinations at Chithurst became particularly poignant for me. At first I had loved witnessing this ancient ceremony as it unfolded: the approach of the candidates, the questioning, and their acceptance into the Bhikkhu Sangha. Then one year I knew I could no longer bring forth that sense of joy; my muditā failed me. I stayed away.

It was clear to me that there was no one to blame for this and, gradually, I was able to appreciate that, as nuns in a Western context, we had a particularly interesting – and challenging – position. Most of the nuns in Thailand do not have a role that is equivalent to that of the monks. However, at Chithurst Monastery, in August, 1983, Ajahn Sumedho had provided the opportunity for the first four of us to receive pabbajjā, relinquishing the use of money in order to go forth as alms mendicants. Later on, he had also arranged for Ajahn Sucitto to help us devise equivalent rules and procedures for our community life. In effect this could allow the priceless legacy of Luang Por Chah to take root and ripen in Western soil, in a way that could be meaningful for both women and men of any nationality.

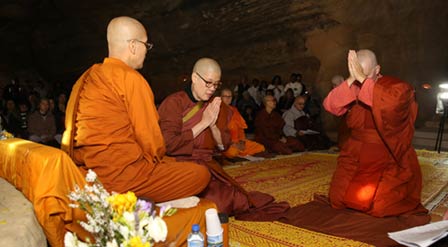

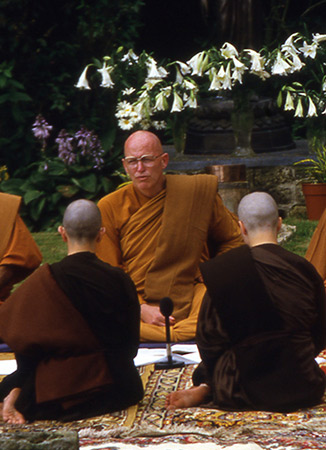

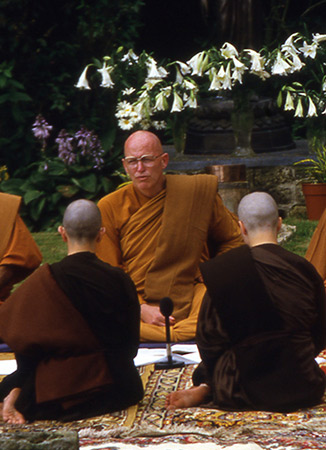

Ceremony of acceptance into the Order of Sīladharā

I would bring to mind our own beautiful and dignified ceremony of acceptance into the Order of Sīladharā, and that we have an excellent training, with rules and community procedures that reflect the style of practice of both the bhikkhus and the early nuns. It is these that enable us to live a renunciate life in community, either as eight precept anagārikās or as sīladharā. Just as for the monks, our vinaya rules are extraordinary in their capacity to reveal any self-concern as a prelude to letting go, to the liberation of the heart….

There were times when I would use these reflections to muster the courage to continue in our small community, as we lived alongside the Bhikkhu Sangha that seemed so much larger, more powerful and well-established; or when Sisters would decide to leave to continue their practice elsewhere; or when, at times, it seemed that we might disappear altogether!

Among people who speak with me, there are a number for whom the question of whether or not we should become bhikkhunīs is a matter of concern. For some of the sīladharā it’s a non-issue, it being clear that both the spiritual and material support we receive as nuns is perfectly adequate for our practice of Dhamma. For others, including me, it continues to be a matter of some interest. Should, at any time, there be the blessing of the elders of our community, together with a satisfactory agreement on how the numerous rules of the bhikkhunī pātimokkha would be interpreted, I could well be among the first to make the request. However, I’m not in a hurry, I’m glad that I can continue as I am – until it becomes clear, if or when, that is to be the next step in this extraordinary unfolding.

I know that what’s needed is simply to pursue the training we have undertaken with sincerity and care. In this way, there can be the ripening of fruits that manifest in a joyousness, understanding and compassion that can benefit everyone. I’m really content to be a daughter of the Buddha, alongside the countless others of different styles of practice, and continuing in the footsteps of Venerable Mahāpajāpatī. I recollect the foremost arahant bhikkhunis as a reminder that each of us has the capacity for perfect freedom from every kind of suffering. This, surely, is something we can all celebrate.

I bow in gratitude to all my spiritual friends (kalyānamittā) and teachers, especially to Luang Por Sumedho, and to all those women I have lived with as Sisters over the years. They have provided – and continue to provide – a clear mirror in which the pockets of greed, aversion and delusion lurking in consciousness can be revealed, acknowledged and let go of. It’s like the pond here at Milntuim Hermitage where, on a still morning, a reflection is seen of every twig, cloud or blade of grass. They can seem so real and cause such distress – but the mind, liberated, knows otherwise.

I bow in gratitude to all my spiritual friends (kalyānamittā) and teachers, especially to Luang Por Sumedho, and to all those women I have lived with as Sisters over the years. They have provided – and continue to provide – a clear mirror in which the pockets of greed, aversion and delusion lurking in consciousness can be revealed, acknowledged and let go of. It’s like the pond here at Milntuim Hermitage where, on a still morning, a reflection is seen of every twig, cloud or blade of grass. They can seem so real and cause such distress – but the mind, liberated, knows otherwise.

May we all know perfect liberation!

Header photo from “Doors to the Deathless are Open” p.87

Used by permission of Ajahn Candasiri, Ajahn Sundara and Ajahn Amaro

Sister Candasirī was born in Scotland. She was one of the first group of nuns to be ordained by Ajahn Sumedho – who was the first Western disciple of the deeply respected Thai master, Venerable Ajahn Chah – at Chithurst Forest Monastery. She took the Eight Precepts as an anagārikā in 1979 and the Ten Precepts, going forth as a sīladhara in 1983. Since then, and until 2012 she lived at either Chithurst or Amaravati Buddhist Monasteries. Now she is living in Perthshire in Scotland where a small hermitage for nuns of her community is being established.

I never, ever, imagined that I would be a nun – of any tradition – even though the experience I had had of monastic life on a couple of retreats in Christian monasteries, though difficult, had seemed utterly fulfilling. I loved the fact that it enabled a whole-hearted commitment to Truth: to realising it and living it out in daily life; and the opportunity to live in a community of people with a similar aspiration. I saw too that there were wider benefits in that people living in such a way can exemplify wholesome qualities that are so needed in our present day society.

I never, ever, imagined that I would be a nun – of any tradition – even though the experience I had had of monastic life on a couple of retreats in Christian monasteries, though difficult, had seemed utterly fulfilling. I loved the fact that it enabled a whole-hearted commitment to Truth: to realising it and living it out in daily life; and the opportunity to live in a community of people with a similar aspiration. I saw too that there were wider benefits in that people living in such a way can exemplify wholesome qualities that are so needed in our present day society.

This, still, is my passion.

It was attending a ten-day retreat over the new year time in 1978/9, led by Ajahn Sumedho at Oakenholt Buddhist Centre near Oxford, that both awakened and confirmed my interest in making a monastic commitment. This was a movement of the heart; the head, the rational mind was profoundly surprised. ‘I’m going to be a Buddhist nun!’ were the words of amazement that would arise in consciousness as I went about my daily life in Edinburgh.

People would ask me what was most difficult to give up when I became a nun. The answer – to the surprise of some – is: ‘Having my own way.’ I had entered the monastic community drawn by a conviction that there is nothing, other than the liberation of the heart, that is worth pursuing. What I was not prepared for was the reality of spiritual companions who, although having a similar aspiration, seemed in every other way to be at odds with my own background personality.

Sisters Sundara, Candasiri, and Rocana

I didn’t particularly want to be a nun living in a community of other nuns. The ego personality was profoundly affected when it became clear that this was what, in effect, I had committed myself to. For the first months, although the four of us were clearly some sort of a group as we worked and meditated alongside the monks at Chithurst, I still managed to feel special. Over time, this changed. There was pressure to conform: to bow and chant together, to be part of a community of nuns. This may seem like a small thing but, for me, it was a huge turning point on the journey of letting go… especially, of the need to be different.

I had always known, theoretically, that as women we would be ‘junior’ to members of the male monastic community. During the early years, the sense of gratitude, devotion and respect that I had for Ajahn Sumedho and the other bhikkhus made the expected outward expression of deference easy and natural – even though it was the opposite of what was expected in the culture I had grown up in and in which we were living. One time at Chithurst, one of a group of Anglican priests who were visiting commented to Ajahn Sumedho his sense of outrage at seeing us on our knees serving him orange juice! Whereas for me, this had become completely normal – a pleasure to be able to serve my teacher in that way.

We served a lot in those days. Everyone worked hard and served in their own way; the monks with many hours each day of heavy building work – there was very little money to pay for the extensive renovation work needed to make the house at Chithurst into a suitable monastic dwelling. As nuns, we cooked, helped with driving, book-keeping and correspondence, and helped to bring the gardens to a state of semi-order. That’s what we did… and, importantly, I felt I belonged.

For me, the move to Amaravati in 1984 represented a major shift. It had been decided that all of the nuns would move to the newly purchased site in Hertfordshire as, by that time our cottage, outbuildings and nearby kutis simply couldn’t accommodate all of us nuns and our guests. Chithurst would be the main training monastery for the monks and, accordingly, kept as a quieter and more secluded residence.

The nuns’ community walked in relays, making the journey as a pilgrimage to our new training monastery. We arrived 2nd August, 1984. A rainbow appeared as we circumambulated the field and made our way into one of the recently vacated huts where a shrine had been created. There, we joined with Ajahn Sumedho, Ajahn Sucitto – who was now, officially, responsible for our training – and the other monks and anagarikas in chanting ‘Jayanto’ – the Buddha’s victory chant.

‘Nuns’ training monastery’, ‘retreat centre’, ‘interfaith library and conference centre’, ‘site for Buddhist festivals and family activities’ and, perhaps, even ‘a crematorium’ – were among the ideas that comprised the initial vision for the place. First of all, though, a substantial debt – together with an urgent need to repair 600 rotting window frames and insulate the large wooden huts – ensured that the whole community quickly acquired new skills and put them to use. I enjoyed the work and, once again, felt happy to be part of something bigger. Ajahn Sumedho had a charisma that inspired and drew everyone together; Ajahn Sucitto met with our nuns’ community regularly to guide us in the basics of monastic training.

Nuns and Ajahn Sumedho

However, it didn’t take very long for the disparity between the positions of the monks and nuns, that was such an unquestioned aspect of Sangha life in Thailand, to become apparent. This was particularly the case for some of the Western visitors who, even then, in the mid 1980’s, were keenly sensitive to any sense of inequality. I could see that this was challenging for Ajahn Sumedho who really wanted us to focus on our practice for liberation, rather than be distracted by concerns regarding the relative status of others. He began to use the community breakfast times of morning reflection to remind us all of these basic principles of practice – sometimes speaking quite strongly. I was dispirited by the tone of his address – even although I found it inspiring and agreed with what he said.

While living as a lay person, my gender was integral to my way of being – to the extent that it wasn’t something that I thought about very much. However, strangely, when I entered the sangha it assumed a vital importance in terms of all my relationships. While I loved to be serving, giving myself to something that offers such a remarkable structure, way of practice and teaching, there was also a sense of sorrow that, as a nun, I could never be fully included. The monks’ ordinations at Chithurst became particularly poignant for me. At first I had loved witnessing this ancient ceremony as it unfolded: the approach of the candidates, the questioning, and their acceptance into the Bhikkhu Sangha. Then one year I knew I could no longer bring forth that sense of joy; my muditā failed me. I stayed away.

It was clear to me that there was no one to blame for this and, gradually, I was able to appreciate that, as nuns in a Western context, we had a particularly interesting – and challenging – position. Most of the nuns in Thailand do not have a role that is equivalent to that of the monks. However, at Chithurst Monastery, in August, 1983, Ajahn Sumedho had provided the opportunity for the first four of us to receive pabbajjā, relinquishing the use of money in order to go forth as alms mendicants. Later on, he had also arranged for Ajahn Sucitto to help us devise equivalent rules and procedures for our community life. In effect this could allow the priceless legacy of Luang Por Chah to take root and ripen in Western soil, in a way that could be meaningful for both women and men of any nationality.

Ceremony of acceptance into the Order of Sīladharā

I would bring to mind our own beautiful and dignified ceremony of acceptance into the Order of Sīladharā, and that we have an excellent training, with rules and community procedures that reflect the style of practice of both the bhikkhus and the early nuns. It is these that enable us to live a renunciate life in community, either as eight precept anagārikās or as sīladharā. Just as for the monks, our vinaya rules are extraordinary in their capacity to reveal any self-concern as a prelude to letting go, to the liberation of the heart….

There were times when I would use these reflections to muster the courage to continue in our small community, as we lived alongside the Bhikkhu Sangha that seemed so much larger, more powerful and well-established; or when Sisters would decide to leave to continue their practice elsewhere; or when, at times, it seemed that we might disappear altogether!

Among people who speak with me, there are a number for whom the question of whether or not we should become bhikkhunīs is a matter of concern. For some of the sīladharā it’s a non-issue, it being clear that both the spiritual and material support we receive as nuns is perfectly adequate for our practice of Dhamma. For others, including me, it continues to be a matter of some interest. Should, at any time, there be the blessing of the elders of our community, together with a satisfactory agreement on how the numerous rules of the bhikkhunī pātimokkha would be interpreted, I could well be among the first to make the request. However, I’m not in a hurry, I’m glad that I can continue as I am – until it becomes clear, if or when, that is to be the next step in this extraordinary unfolding.

I know that what’s needed is simply to pursue the training we have undertaken with sincerity and care. In this way, there can be the ripening of fruits that manifest in a joyousness, understanding and compassion that can benefit everyone. I’m really content to be a daughter of the Buddha, alongside the countless others of different styles of practice, and continuing in the footsteps of Venerable Mahāpajāpatī. I recollect the foremost arahant bhikkhunis as a reminder that each of us has the capacity for perfect freedom from every kind of suffering. This, surely, is something we can all celebrate.

I bow in gratitude to all my spiritual friends (kalyānamittā) and teachers, especially to Luang Por Sumedho, and to all those women I have lived with as Sisters over the years. They have provided – and continue to provide – a clear mirror in which the pockets of greed, aversion and delusion lurking in consciousness can be revealed, acknowledged and let go of. It’s like the pond here at Milntuim Hermitage where, on a still morning, a reflection is seen of every twig, cloud or blade of grass. They can seem so real and cause such distress – but the mind, liberated, knows otherwise.

I bow in gratitude to all my spiritual friends (kalyānamittā) and teachers, especially to Luang Por Sumedho, and to all those women I have lived with as Sisters over the years. They have provided – and continue to provide – a clear mirror in which the pockets of greed, aversion and delusion lurking in consciousness can be revealed, acknowledged and let go of. It’s like the pond here at Milntuim Hermitage where, on a still morning, a reflection is seen of every twig, cloud or blade of grass. They can seem so real and cause such distress – but the mind, liberated, knows otherwise.

May we all know perfect liberation!

Header photo from “Doors to the Deathless are Open” p.87

Used by permission of Ajahn Candasiri, Ajahn Sundara and Ajahn Amaro