How I Became a Bhikkhuni

by Venerable Dr. Bhikkhuni Kusuma

How I Became a Bhikkhuni

by Venerable Dr. Bhikkhuni Kusuma

Article first printed in the Sakyadhita Newsletter, Summer 2008, Vol. 16, Number 2 edition.

`Oh Maharaja, until a person in the soil of the land takes ordination, the ordination will not be established in the land.’

We are so happy that we were born in the soil of the land and received ordination and will establish as the Bhikkhuni Sangha

Many people invited me to write my story. I always declined but, while in Berlin, Gabriele Kustermann insisted `here is the paper and pen you write now.’ It was an order from a highly revered friend. So, I sat down and wrote a few pages, but alas! That was the beginning and the end of the story. This is a brief story, to be included in the Sakyadhita News Letter as invited by the organisers.

It is 10 years, since I ordained as the first Bhikkhuni at Sarnath India. It is past history now and was very controversial. People started writing and publishing their personal views about the ordination, and there were misinterpretations and without factual evidence. There were the Theravada monks – some supportive, some opposing. It was too much to handle and became headline news in the daily paper. The `Resurrection of the Bhikkhuni Order!’ Since I had achieved my purpose, I thought it would be prudent to be silent. Have I inadvertently upset a Hornet’s nest, by becoming ordained as a Bhikkhuni?

At the `defense of the thesis’ of my research, there were very senior monks on the board, and they asked me questions of Vinaya, which they really did not know about. I was able to clarify and I answered to their satisfaction and was awarded the PhD degree.

But, my intention was clear. I have been a Vinaya research scholar for the past twenty years and was fully cognizant about Vinaya procedures. This is maybe one reason that nobody confronted me directly. Even the monks had not studied the Bhikkhuni Vinaya. At the `defense of the thesis’ of my research, there were very senior monks on the board, and they asked me questions of Vinaya, which they really did not know about. I was able to clarify and I answered to their satisfaction and was awarded the PhD degree. The next important episode in my life was the Sakyadhita conference held in Sri Lanka in 1991. Ranjani and I who were the main organisers became `activists’ to re-introduce the Bhikkhuni order in Sri Lanka. She was the Secretary and I was the President of Sakyadhita Sri Lanka. We approached Ven. Mapalagama Vipulasara Thero, the President of the Mahabodhi Society of India. He was also the Founder, Member and Secretary of the World Buddhist Sangha Council. We asked him about the possibility of resurrecting the Bhikkhuni order.

After much deliberation, he communicated with the Korean sangha of the Chogya Order. They were very willing, but it was a question of feasibility and a question of finances to set about it.

It was decided that Sri Lanka could not be the venue for the ordination ceremony because of the possible opposition, where as in Sarnath, India under the auspices of the India Mahabodhi society, it could be possible. So, it was decided to select ten candidates to be ordained in India and they had to stay in India for two years after ordination to receive training as Bhikkhunis. This meant board and lodging and traveling to India. The building that was the living quarters of Anagārika Dhamapāla, was one hundred years old and had to be renovated at great cost to house the Bhikkhunis.

I must gratefully acknowledge all this enormous amount of energy and money that was spent by Ven. Vipulasara Thero mainly with the cooperation from the Korean Sangha.

It was a crucial question of selecting the ten nuns to receive ordination. It was advertised in the local newspapers and about two hundred applicants turned up for the interview. But, the moment they heard about the prevailing opposition of monks and the training for two years, they were reluctant, as it would mean leaving their temples and residing in India. Ranjani and some ladies were on the interview board and nine nuns were finally selected. They were to be given eight months of training at Parama Dhamma Cetiya Privena in Ratamalana, Sri Lanka prior to their departure to India. I was one of the teachers of these nuns in Vinaya and the Dharma.

In the midst of this, Ven. Vipulasara called me up one day and said, `you have to go to Korea and study their ordination procedure.’ It was quite an order and I had no valid reason to refuse. I had been meditating, wearing white and living as a recluse for over fifteen years – ever since the death of my twenty one year old daughter. I retired at the age of 55 from the University of Sri Jayawandanapura after 20 years of teaching, having done my post graduate studies in Pali, Buddhism and Vinaya. So the venerable monk selected me to perform this onerous duty.

Soon I found myself in Bo-Myunsa, the famous Korean Temple in Kwanik-Ku in Seoul, Korea in the middle of winter. Hardly anyone spoke English except for the Abbess, the Maha Bhikkhuni Ven. Sang Wong. In spite of the extreme difficultly I stayed for 3 months and read through the Vinaya in English translation.

To my greatest satisfaction, I found that the Vinaya and the ordination procedure were the same as the Sri Lankan tradition. There is a reason for this.

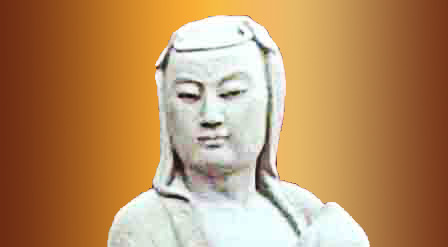

All the nuns in the world today are descendants of Sri Lankan Bhikkhunis, who claimed lineage from Ven. Bhikkhuni Maha Prajapati at the time of the Buddha.

Ven. Sanghamitta brought the Bhikkhuni ordination to Sri Lankan in the 3rd century B.C. and in the 6th century A.D. the order was taken to China along the `Silk Route’ by Sri Lankan nuns. They crossed the dangerous seas by sailing boats belonging to a man named Nandi. This is Chinese history as well. Prof. Hema Gunatilleka has published this report having done much research on the subject. From China the order spread to Japan, Korea, Taiwan and most of the `Mahayana’ countries. Thus, it will be seen that all the nuns in the world today are descendants of Sri Lankan Bhikkhunis, who claimed lineage from Ven. Bhikkhuni Maha Prajapati at the time of the Buddha.

I translated the Vinaya procedure to the Sri Lankan language – Sinhala while in Korea to be read by the Sri Lankan nuns seeking ordination. The nuns studied this material beforehand and were acquainted with the ordination procedure.

Korean Ordination:

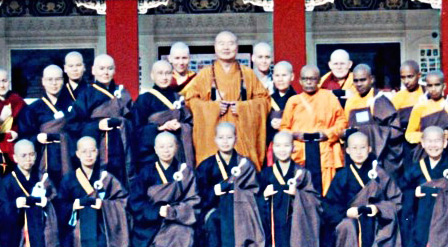

While I was in Korea, the Korean Maha Sangha and lay people numbering over 150 were preparing to come to India to bestow ordination to the Sri Lankan nuns. They had booked the air tickets and made elaborate plans to perform this very important historic ceremony.

In the meantime, there was a massive public opinion mounting up in Sri Lanka. The monks who were supporting Ven. Vipulasara declined, and even Ranjani wrote to me that it is best to give up the ordination in the face of opposition from Theravada monks. It was a crucial decision to make and Ven. Vipulasara telephoned me from Sri Lanka and intimated the facts. We were alarmed in Korea. The Korean Sangha even doubted the pure intention of Ven. Vipulasara!

Ven. Vipulasara continued on the telephone, saying that he felt even the nuns selected were not of the required standard to receive ordination as their language skills and knowledge, etc. were not adequate. `It is an international responsibility’ he said, and in the face of it all he wanted me to join the nuns and take a leadership role as the first Bhikkhuni. If not he was constrained to abandon the whole project! I was caught between two worlds and had hardly any time to think. I replied `Ven. Sir, please do not abandon the project, even at the risk of my life I will be willing, there never will be another chance.’ And so it was decided to go ahead and Ven. Vipulasara hung up the receiver. This indeed was how I decided to become a Bhikkhuni.

But, the Korean Sangha was not satisfied. They were becoming doubtful and questioned the credibility of Ven.Vipulasara. They decided to invite Ven. Vipulasara to Korea and questioned him in great detail. Ven. Vipulasara arrived in Korea and was interrogated by the Maha Sangha behind closed doors, with the help of an interpreter. Even the Maha Bhikkuni and I were excluded. But, as the Devas deemed it and fate decreed, Ven. Vipulasara spoke up and dispelled their consternation. So it was finally decided to hold the ordination.

My ordination as a 10 precept nun (Dasasil Mathawa):

Shortly afterwards, I returned to Sri Lanka and received ordination as a 10 precept nun at the Kelaniya Rajamaha Vihara under the tutelage of Ven. Kollupitiya Mahinda Thero, the chief incumbent monk. There was a record crowd to witness this ceremony. Many people in Sri Lanka knew me. I was on the Sri Lanka State Broadcasting radio weekly Buddhist forum for over 18 years. Sri Lankan being a small island nation, many people knew me. There were tears shed when I took leave of my husband and family. People showered me with gifts. It mounted up in a heap in front. I was the happiest, as I donned the yellow robe.

Higher ordination in Sarnath:

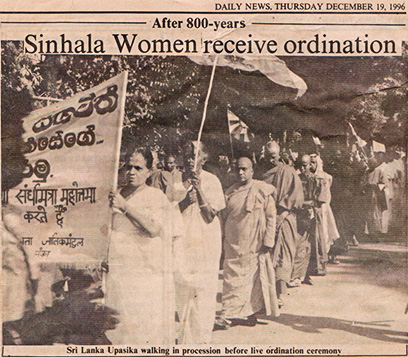

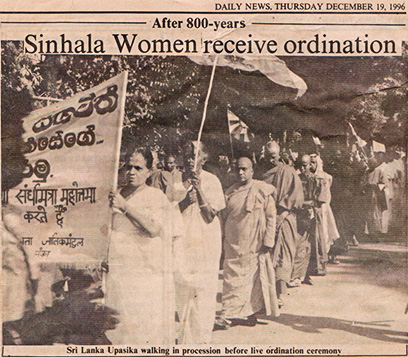

Historic Newspaper Clipping – December 1996

It was quite unexpected for me and my family, that I should be in India to receive higher ordination as a Bhikkhuni and that I will be residing in Sarnath for two years for further training as a Bhikkhuni. It was not an enviable position for me in the light of the opposition but, I pledged, even at the risk of my life and my mind was made up. We proceeded to India shortly.

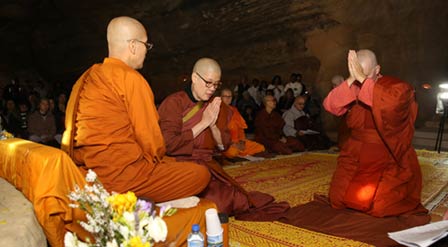

On the 8th of December 1996, there was unimaginable splendor at the Sarnath Mahabodhi premises. We were taken in procession complete with caparisoned elephants and horses. There were large crowds carrying flags, Sri Lankan pilgrims and nuns. Bhikkhus had arrived from Sri Lanka, Thailand and many other countries to witness the ceremony. I remember the presence of Ven. Lekshe Tsomo, the international president of Sakyadhita.

The venue was the very spot where the Buddha preached the first sermon – Dhamma Chakka Pavattana Sutta (The Turning of the Wheel of Dhamma Sutta), to the five ascetics. There were the ordaining masters, both Bhikkus and Bhikkunis, of the Korean Sangha and an interpreter to translate from Korean to the English language. It was my sacred duty to translate the ongoing procedure from English to Sinhala for the other nuns seeking ordination. The ceremony took eight hours and the discipline and formality was austere. My knees ached by bleeding and kneeling. I can see the scars even now as a reminder of this most auspicious day.

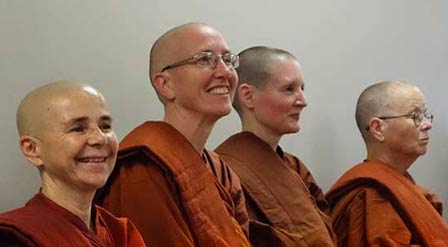

First, we took ordination from Bhikkhunis and the second ordination from Bhikkus as was the tradition from the time of the Buddha. We were dressed in ceremonial Korean robes and it was a magnificent sight. Many photos and videos were taken which flashed across Sri Lankan n newspapers and around the world communities. It was publicly acclaimed around the world. My friends in the UK, mostly doctors, chartered a special plane to come to Sarnath to see me. The Sri Lankan newspapers published headline news of this event, with many speaking for and against the ordination.

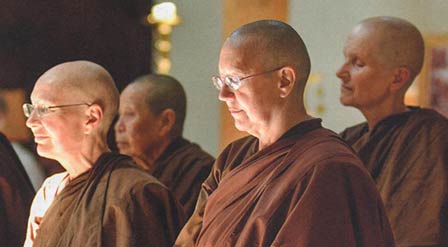

But, I knew that my Dhamma is proceeding along the Theravada Pali tradition and for two years a very senior Sri Lankan monk Ven. Pundit Andawala Devasiri Thero, took over the training in Sarnath. We were offered Sri Lankan robes as the Sri Lankan monks recognized the ordination. I was the first to be ordained and so I was considered the first Bhikkhuni among nine others.

It was a sacrifice indeed, but I am ever grateful to one and all for the kind help towards the establishment of the Bhikkhuni order in Sri Lanka after a lapse of about thousand years. In conclusion, I like to quote from the Mahavansa.

There is a famous statement in the Mahavansa – our ancient Sri Lankan historical chronical, uttered by Ven. Mahinda who brought ordination to Sri Lanka in the 3rd century B.C. He addressed the king:

`Oh Maharaja, until a person born in the soil of the land takes ordination, the ordination will not be established in the land.’

We are so happy that we were born in the soil of the land received ordination and will establish as the Bhikkhuni Sangha of Sri Lanka. It is up to the future Bhikkhunis to continue to live according to the precepts and practice and keep the wisdom of the Buddha alive.

Nibbanam Paramam Sukham!

Venerable Dr. Bhikkhuni Kusuma responded below to questions posed by Donna McCarthy.

What things influenced your decision to take the Bhikkhuni path?

As a lay person in the 1950’s & 60’s, my initial interest was in the field of Science. In 1969 after my studies in Molecular Biology in USA, I realised that there are no real answers in Science to the beginning and end of life. I then decided to study Pali and Buddhist philosophy to find answers to these questions. I spent my time reading the ‘Tripitaka’ and started my journey in search of the truth. I went on to write my MA thesis on “Sati-in Buddhist Meditation, A Mental Therapy” and started my PhD studies in 1982 on the Buddhist nuns of Sri Lanka. Thereafter, I read for my second PhD thesis on the 311 rules of Vinaya for Bhikkunis.

Having studied the history of Bhikkhunis in Sri Lanka, I was also very interested in resurrecting the Bhikkuni order here. For more than 10 years, I met many influential people in the government, various Buddhist monks and nuns and had discussions.

How did the ordination all come about?

I had no idea of becoming a Bhikkuni myself. I was invited by the organisers to lead the Bhikkunis. Please read `How I became a Bhikkuni’ which is enclosed. The idea of resurrecting the Bhikkhuni order in Sri Lanka was there about 100 years before. Professor G.P. Malalasekera, Venerable Anagārika Dharmapāla and others had submitted papers, but it did not materialize.

What were you feeling before and after the ceremony?

I think it was a shock. I hardly felt any elation. The future was uncertain….risky amidst opposition from the Theravāda monk hierarchy. I felt a criminal going against the powerful, established, government sponsored monk order. In fact, I lost my status as a University don and actually went into hiding in a remote village in Olaboduwa without any support. So, I resigned myself thinking `well my task is done, maybe the Bhikkuni order will flourish and will eventually get the recognition that they deserve. It takes time to break through tradition, cultural supremacy of the Sangha, etc., that was deeply rooted in the minds of the Sri Lankan people going back to thousands of years.’

At the time, people thought our ordination was a hoax because it did not get the necessary publicity. I am still alive to give firsthand information about the ordination with hundreds of photos, newspaper accounts, etc. I cordially invite you to visit me and scrutinize the documents and preserve them if necessary. As it is, it will die a natural death, with me now at 88 years of age.

What do you remember about the other women who ordained and what they were thinking and feeling?

The nuns had their own establishment as 10 precepts nuns and had their own ārāmas. We met occasionally. I had no place to stay so, I started building the Ayya Khema Meditation Centre which took nearly 15 years. It is well established now and I’m the happiest and most fortunate person today. Lack of transport, poor health and old age is catching up fast. Also, in a `third world country’ such as Sri Lanka, technology and communication is not adequate as one would imagine in the western `first world countries.’ So, please bear with us for our seeming lethargy and inadequacy!

“I emphasized all of this in my PhD thesis on the “Nuns of Sri Lanka and Bhikkhuni Vinaya.”

How has Maha Prajāpati’s decision to request ordination from the Buddha 2600 years ago had an impact on your life today?

I felt my sacrifice of leaving my home and family is nothing compared to Maha Prajāpati. She suffered walking barefoot about 200 miles from Kapilavastu to Vesali and was humiliated. As the story goes, she created massive public opinion and there was none who opposed her. According to my own research on this Bhikkuni Vinaya, I find that she was great to don the yellow robes inspite of Bhddha’s so called `refusal.’ I also find that the Buddha never refused to ordain, but was waiting for the right time. Please refer to my PhD theses on Bhikkuni Vinaya. Venerable Tatthaloka will have a copy.

I feel happy that my humble efforts are being recognized by you and others. It is not a personal glory, but a case of resurrecting the four-fold society that the Buddha instituted and women obtaining their rightful place in the Sāsana.

Ven. Dr. Bhikkhuni Kusuma

Article first printed in the Sakyadhita Newsletter, Summer 2008, Vol. 16, Number 2 edition.

`Oh Maharaja, until a person in the soil of the land takes ordination, the ordination will not be established in the land.’

We are so happy that we were born in the soil of the land and received ordination and will establish as the Bhikkhuni Sangha

Many people invited me to write my story. I always declined but, while in Berlin, Gabriele Kustermann insisted `here is the paper and pen you write now.’ It was an order from a highly revered friend. So, I sat down and wrote a few pages, but alas! That was the beginning and the end of the story. This is a brief story, to be included in the Sakyadhita News Letter as invited by the organisers.

It is 10 years, since I ordained as the first Bhikkhuni at Sarnath India. It is past history now and was very controversial. People started writing and publishing their personal views about the ordination, and there were misinterpretations and without factual evidence. There were the Theravada monks – some supportive, some opposing. It was too much to handle and became headline news in the daily paper. The `Resurrection of the Bhikkhuni Order!’ Since I had achieved my purpose, I thought it would be prudent to be silent. Have I inadvertently upset a Hornet’s nest, by becoming ordained as a Bhikkhuni?

At the `defense of the thesis’ of my research, there were very senior monks on the board, and they asked me questions of Vinaya, which they really did not know about. I was able to clarify and I answered to their satisfaction and was awarded the PhD degree.

But, my intention was clear. I have been a Vinaya research scholar for the past twenty years and was fully cognizant about Vinaya procedures. This is maybe one reason that nobody confronted me directly. Even the monks had not studied the Bhikkhuni Vinaya. At the `defense of the thesis’ of my research, there were very senior monks on the board, and they asked me questions of Vinaya, which they really did not know about. I was able to clarify and I answered to their satisfaction and was awarded the PhD degree. The next important episode in my life was the Sakyadhita conference held in Sri Lanka in 1991. Ranjani and I who were the main organisers became `activists’ to re-introduce the Bhikkhuni order in Sri Lanka. She was the Secretary and I was the President of Sakyadhita Sri Lanka. We approached Ven. Mapalagama Vipulasara Thero, the President of the Mahabodhi Society of India. He was also the Founder, Member and Secretary of the World Buddhist Sangha Council. We asked him about the possibility of resurrecting the Bhikkhuni order.

After much deliberation, he communicated with the Korean sangha of the Chogya Order. They were very willing, but it was a question of feasibility and a question of finances to set about it.

It was decided that Sri Lanka could not be the venue for the ordination ceremony because of the possible opposition, where as in Sarnath, India under the auspices of the India Mahabodhi society, it could be possible. So, it was decided to select ten candidates to be ordained in India and they had to stay in India for two years after ordination to receive training as Bhikkhunis. This meant board and lodging and traveling to India. The building that was the living quarters of Anagārika Dhamapāla, was one hundred years old and had to be renovated at great cost to house the Bhikkhunis.

I must gratefully acknowledge all this enormous amount of energy and money that was spent by Ven. Vipulasara Thero mainly with the cooperation from the Korean Sangha.

It was a crucial question of selecting the ten nuns to receive ordination. It was advertised in the local newspapers and about two hundred applicants turned up for the interview. But, the moment they heard about the prevailing opposition of monks and the training for two years, they were reluctant, as it would mean leaving their temples and residing in India. Ranjani and some ladies were on the interview board and nine nuns were finally selected. They were to be given eight months of training at Parama Dhamma Cetiya Privena in Ratamalana, Sri Lanka prior to their departure to India. I was one of the teachers of these nuns in Vinaya and the Dharma.

In the midst of this, Ven. Vipulasara called me up one day and said, `you have to go to Korea and study their ordination procedure.’ It was quite an order and I had no valid reason to refuse. I had been meditating, wearing white and living as a recluse for over fifteen years – ever since the death of my twenty one year old daughter. I retired at the age of 55 from the University of Sri Jayawandanapura after 20 years of teaching, having done my post graduate studies in Pali, Buddhism and Vinaya. So the venerable monk selected me to perform this onerous duty.

Soon I found myself in Bo-Myunsa, the famous Korean Temple in Kwanik-Ku in Seoul, Korea in the middle of winter. Hardly anyone spoke English except for the Abbess, the Maha Bhikkhuni Ven. Sang Wong. In spite of the extreme difficultly I stayed for 3 months and read through the Vinaya in English translation.

To my greatest satisfaction, I found that the Vinaya and the ordination procedure were the same as the Sri Lankan tradition. There is a reason for this.

All the nuns in the world today are descendants of Sri Lankan Bhikkhunis, who claimed lineage from Ven. Bhikkhuni Maha Prajapati at the time of the Buddha.

Ven. Sanghamitta brought the Bhikkhuni ordination to Sri Lankan in the 3rd century B.C. and in the 6th century A.D. the order was taken to China along the `Silk Route’ by Sri Lankan nuns. They crossed the dangerous seas by sailing boats belonging to a man named Nandi. This is Chinese history as well. Prof. Hema Gunatilleka has published this report having done much research on the subject. From China the order spread to Japan, Korea, Taiwan and most of the `Mahayana’ countries. Thus, it will be seen that all the nuns in the world today are descendants of Sri Lankan Bhikkhunis, who claimed lineage from Ven. Bhikkhuni Maha Prajapati at the time of the Buddha.

I translated the Vinaya procedure to the Sri Lankan language – Sinhala while in Korea to be read by the Sri Lankan nuns seeking ordination. The nuns studied this material beforehand and were acquainted with the ordination procedure.

Korean Ordination:

While I was in Korea, the Korean Maha Sangha and lay people numbering over 150 were preparing to come to India to bestow ordination to the Sri Lankan nuns. They had booked the air tickets and made elaborate plans to perform this very important historic ceremony.

In the meantime, there was a massive public opinion mounting up in Sri Lanka. The monks who were supporting Ven. Vipulasara declined, and even Ranjani wrote to me that it is best to give up the ordination in the face of opposition from Theravada monks. It was a crucial decision to make and Ven. Vipulasara telephoned me from Sri Lanka and intimated the facts. We were alarmed in Korea. The Korean Sangha even doubted the pure intention of Ven. Vipulasara!

Ven. Vipulasara continued on the telephone, saying that he felt even the nuns selected were not of the required standard to receive ordination as their language skills and knowledge, etc. were not adequate. `It is an international responsibility’ he said, and in the face of it all he wanted me to join the nuns and take a leadership role as the first Bhikkhuni. If not he was constrained to abandon the whole project! I was caught between two worlds and had hardly any time to think. I replied `Ven. Sir, please do not abandon the project, even at the risk of my life I will be willing, there never will be another chance.’ And so it was decided to go ahead and Ven. Vipulasara hung up the receiver. This indeed was how I decided to become a Bhikkhuni.

But, the Korean Sangha was not satisfied. They were becoming doubtful and questioned the credibility of Ven.Vipulasara. They decided to invite Ven. Vipulasara to Korea and questioned him in great detail. Ven. Vipulasara arrived in Korea and was interrogated by the Maha Sangha behind closed doors, with the help of an interpreter. Even the Maha Bhikkuni and I were excluded. But, as the Devas deemed it and fate decreed, Ven. Vipulasara spoke up and dispelled their consternation. So it was finally decided to hold the ordination.

My ordination as a 10 precept nun (Dasasil Mathawa):

Shortly afterwards, I returned to Sri Lanka and received ordination as a 10 precept nun at the Kelaniya Rajamaha Vihara under the tutelage of Ven. Kollupitiya Mahinda Thero, the chief incumbent monk. There was a record crowd to witness this ceremony. Many people in Sri Lanka knew me. I was on the Sri Lanka State Broadcasting radio weekly Buddhist forum for over 18 years. Sri Lankan being a small island nation, many people knew me. There were tears shed when I took leave of my husband and family. People showered me with gifts. It mounted up in a heap in front. I was the happiest, as I donned the yellow robe.

Higher ordination in Sarnath:

Historic Newspaper Clipping – December 1996

It was quite unexpected for me and my family, that I should be in India to receive higher ordination as a Bhikkhuni and that I will be residing in Sarnath for two years for further training as a Bhikkhuni. It was not an enviable position for me in the light of the opposition but, I pledged, even at the risk of my life and my mind was made up. We proceeded to India shortly.

On the 8th of December 1996, there was unimaginable splendor at the Sarnath Mahabodhi premises. We were taken in procession complete with caparisoned elephants and horses. There were large crowds carrying flags, Sri Lankan pilgrims and nuns. Bhikkhus had arrived from Sri Lanka, Thailand and many other countries to witness the ceremony. I remember the presence of Ven. Lekshe Tsomo, the international president of Sakyadhita.

The venue was the very spot where the Buddha preached the first sermon – Dhamma Chakka Pavattana Sutta (The Turning of the Wheel of Dhamma Sutta), to the five ascetics. There were the ordaining masters, both Bhikkus and Bhikkunis, of the Korean Sangha and an interpreter to translate from Korean to the English language. It was my sacred duty to translate the ongoing procedure from English to Sinhala for the other nuns seeking ordination. The ceremony took eight hours and the discipline and formality was austere. My knees ached by bleeding and kneeling. I can see the scars even now as a reminder of this most auspicious day.

First, we took ordination from Bhikkhunis and the second ordination from Bhikkus as was the tradition from the time of the Buddha. We were dressed in ceremonial Korean robes and it was a magnificent sight. Many photos and videos were taken which flashed across Sri Lankan n newspapers and around the world communities. It was publicly acclaimed around the world. My friends in the UK, mostly doctors, chartered a special plane to come to Sarnath to see me. The Sri Lankan newspapers published headline news of this event, with many speaking for and against the ordination.

But, I knew that my Dhamma is proceeding along the Theravada Pali tradition and for two years a very senior Sri Lankan monk Ven. Pundit Andawala Devasiri Thero, took over the training in Sarnath. We were offered Sri Lankan robes as the Sri Lankan monks recognized the ordination. I was the first to be ordained and so I was considered the first Bhikkhuni among nine others.

It was a sacrifice indeed, but I am ever grateful to one and all for the kind help towards the establishment of the Bhikkhuni order in Sri Lanka after a lapse of about thousand years. In conclusion, I like to quote from the Mahavansa.

There is a famous statement in the Mahavansa – our ancient Sri Lankan historical chronical, uttered by Ven. Mahinda who brought ordination to Sri Lanka in the 3rd century B.C. He addressed the king:

`Oh Maharaja, until a person born in the soil of the land takes ordination, the ordination will not be established in the land.’

We are so happy that we were born in the soil of the land received ordination and will establish as the Bhikkhuni Sangha of Sri Lanka. It is up to the future Bhikkhunis to continue to live according to the precepts and practice and keep the wisdom of the Buddha alive.

Nibbanam Paramam Sukham!

Venerable Dr. Bhikkhuni Kusuma responded below to questions posed by Donna McCarthy.

What things influenced your decision to take the Bhikkhuni path?

As a lay person in the 1950’s & 60’s, my initial interest was in the field of Science. In 1969 after my studies in Molecular Biology in USA, I realised that there are no real answers in Science to the beginning and end of life. I then decided to study Pali and Buddhist philosophy to find answers to these questions. I spent my time reading the ‘Tripitaka’ and started my journey in search of the truth. I went on to write my MA thesis on “Sati-in Buddhist Meditation, A Mental Therapy” and started my PhD studies in 1982 on the Buddhist nuns of Sri Lanka. Thereafter, I read for my second PhD thesis on the 311 rules of Vinaya for Bhikkunis.

Having studied the history of Bhikkhunis in Sri Lanka, I was also very interested in resurrecting the Bhikkuni order here. For more than 10 years, I met many influential people in the government, various Buddhist monks and nuns and had discussions.

How did the ordination all come about?

I had no idea of becoming a Bhikkuni myself. I was invited by the organisers to lead the Bhikkunis. Please read `How I became a Bhikkuni’ which is enclosed. The idea of resurrecting the Bhikkhuni order in Sri Lanka was there about 100 years before. Professor G.P. Malalasekera, Venerable Anagārika Dharmapāla and others had submitted papers, but it did not materialize.

What were you feeling before and after the ceremony?

I think it was a shock. I hardly felt any elation. The future was uncertain….risky amidst opposition from the Theravāda monk hierarchy. I felt a criminal going against the powerful, established, government sponsored monk order. In fact, I lost my status as a University don and actually went into hiding in a remote village in Olaboduwa without any support. So, I resigned myself thinking `well my task is done, maybe the Bhikkuni order will flourish and will eventually get the recognition that they deserve. It takes time to break through tradition, cultural supremacy of the Sangha, etc., that was deeply rooted in the minds of the Sri Lankan people going back to thousands of years.’

At the time, people thought our ordination was a hoax because it did not get the necessary publicity. I am still alive to give firsthand information about the ordination with hundreds of photos, newspaper accounts, etc. I cordially invite you to visit me and scrutinize the documents and preserve them if necessary. As it is, it will die a natural death, with me now at 88 years of age.

What do you remember about the other women who ordained and what they were thinking and feeling?

The nuns had their own establishment as 10 precepts nuns and had their own ārāmas. We met occasionally. I had no place to stay so, I started building the Ayya Khema Meditation Centre which took nearly 15 years. It is well established now and I’m the happiest and most fortunate person today. Lack of transport, poor health and old age is catching up fast. Also, in a `third world country’ such as Sri Lanka, technology and communication is not adequate as one would imagine in the western `first world countries.’ So, please bear with us for our seeming lethargy and inadequacy!

“I emphasized all of this in my PhD thesis on the “Nuns of Sri Lanka and Bhikkhuni Vinaya.”

How has Maha Prajāpati’s decision to request ordination from the Buddha 2600 years ago had an impact on your life today?

I felt my sacrifice of leaving my home and family is nothing compared to Maha Prajāpati. She suffered walking barefoot about 200 miles from Kapilavastu to Vesali and was humiliated. As the story goes, she created massive public opinion and there was none who opposed her. According to my own research on this Bhikkuni Vinaya, I find that she was great to don the yellow robes inspite of Bhddha’s so called `refusal.’ I also find that the Buddha never refused to ordain, but was waiting for the right time. Please refer to my PhD theses on Bhikkuni Vinaya. Venerable Tatthaloka will have a copy.

I feel happy that my humble efforts are being recognized by you and others. It is not a personal glory, but a case of resurrecting the four-fold society that the Buddha instituted and women obtaining their rightful place in the Sāsana.

Ven. Dr. Bhikkhuni Kusuma