An Interview with AFB’s Founder,

Susan Pembroke

by Brenna Artinger

An Interview with AFB’s Founder,

Susan Pembroke

by Brenna Artinger

Brenna Artinger (BA): Would you mind telling me a little bit about your background, how you got into Buddhism, and your meditation practice (specifically with teachers such as Ayya Khema)?

Susan Pembroke

Susan Pembroke (SP): I became introduced to Buddhism in the mid-1980s while I was living in Los Angeles, and I went to a center there called Community Meditation Center, which was founded and run by Shinzen Young, and at that time by his wife, Shelly Young. That was really classic, traditional Vipassana practice, and I did that for five or six years. I had the good fortune of sitting with a lot of meditation teachers who came to Los Angeles, people who were in all different traditions; I did a lot of one-day, and weekend, and week retreats. I also sat and did retreats in the Goenka tradition, and [retreats with] different monks who came through. I had the good fortune to do a long-weekend retreat with Robert Hover who studied with U Ba Khin, and so I also became very interested in [body] sweeping. I do jhanas, vipassana, body-sweeping, very traditional vipassana meditation and metta practices. I came across a book by Ayya Khema in the early 1990s and it was a book on the jhanas, among other subjects, and I found it very helpful. I had had an experience of jhana when I was around twelve years old, and I didn’t know what had happened to me; I was born and raised Catholic. So it was was very interesting, and wonderful, and scary at the same time. So when I read her description of jhana I thought, ‘Oh, this is what happened to me,’ and I was able to sit retreats with her when she traveled to the United States.

BA: What were your inspirations and motivations behind founding the Alliance for Bhikkhunis? What needs were you responding to at the time? It’s been 10 years since the AfB was founded, and bhikkhuni ordination (or the revival of bhikkhuni ordination) was fairly new at that time. What were the needs that inspired you to create the organization?

Ayya Khema

SP: I had travelled to Kuala Lumpur to attend the Sakyadhita conference there. I had an interest in Sakyadhita for a number of years because Ayya Khema was one of the founders of Sakyadhita. She was really an advocate for women monastics, and that organization obviously was, and continues to be, very helpful in advocating for monastics. So I just simply went with the desire to be with other Buddhist women and [to learn]. And I met at that time three Thai bhikkhunis who had just been ordained months before in Ayutthaya, which is an old Buddhist site in Thailand, with wonderful ancient ruins and temples. They really did it off the radar. It is banned still to ordain bhikkhunis in Thailand. And the people who ordained them were Mahayana bhikkshus and bhikkshunis. I struck up a conversation and friendship with them. They seemed so oppressed to me at that time. There were only four bhikkhunis in Thailand at the time: Ayya Dhammananda (who is very well known, she lives outside of Bangkok), who went to Sri Lanka to ordain; and then these three women who were very vulnerable, without support. I work as a psychotherapist, they just looked clinically depressed to me, and really even frightened for their safety. And so I said to them, ‘I’ll help you,’ not even really knowing what that meant. And I just wanted to send them some money, not a lot, $5,000-10,000 or something, so that they could get some land so they could start a monastery. The male monks there had tremendous support and all kinds of grants, and free education, and healthcare, and they just really had nothing. Then once I got home I realized, I can’t just raise money and send it there, I have to start a non-profit. So, that’s how the Alliance for Bhikkhunis started.

BA: Were the bhikkhunis that you were helping at the time mostly in Asia, in Thailand and Sri Lanka, was that the core of how it started? Was there a point when the organization spread West to the U.S. and Europe?

SP: I really was just focusing on Thailand because I just assumed that women in other countries, especially Western countries, were fine. This is how little I knew at the time. When I began it, I asked a Ventura-based Sri Lankan monk, Bhante Sutadhara for suggestions. He said, ‘there is a woman in Northern California who is a bhikkhuni’. He was talking about Ayya Tathaaloka, I didn’t know her. I just wrote to her out of the blue, and I went to visit her later that year, or early 2007. I learned what a tough time American women were having due to little or no organized support.

BA: To move on to the next question, what were some of the early challenges of starting a nonprofit? I can imagine it must have been fairly challenging to create this whole organization to support women. So what were some of the more specific needs that were challenging for getting the organization up and running?

SP: I really found that first part amazingly simple. People just appeared out of nowhere to help me, magically. A friend Michael Shiffman said, ‘this Mancuso book is a very good book for starting nonprofits.’ He had used it to start LA Dharma. Somebody who I meditated with said, ‘I know this attorney who starts nonprofits pro bono. Lucinda Green of Rocky Mountain Insight Colorado sent me the template that she used for starting a non-profit. Then, Ayya Tathaaloka somehow connected me to the Australian monk, Bhante Sujato, who said, ‘we have a monk here who will create a website for you.’ So everything was served up on a silver platter for me, and I just tapped some of my friends to be on the board. One of them is still on the board, Marsha Morrow. They just volunteered and helped. People have been extremely kind. Within a short amount of time it came together.

BA: That’s pretty amazing that is just all fell into place. For the earlier days of the organization, you mentioned how it started in Thailand as the inspiration for the organization. What were some of the early projects that were happening? What did those projects entail? If you could give us a couple of examples.

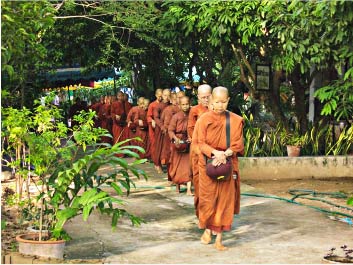

SP: It became clear to me that not only did I not know very much about bhikkhunis, but many people who identified as Buddhist didn’t know very much either. Much of first years was spent educating myself about bhikkhunis and their history and current achievements as well as challenges. I took multiple trips to Thailand. On one trip I went on a tour of different bhikkhuni monasteries there. I also went with Carol Annable, one of AfB’s most illustrious and hard-working vice presidents, to Sri Lanka and met quite a few women over there. Sri Lanka is way ahead of Thailand, and way ahead of Burma when it comes to ordaining bhikkhunis and supporting them. The Sri Lankan monks have been very pro-bhikkhunis, and have been tremendous leaders in helping women ordain. Australian bhikkhus have also been champions of bhikkhuni ordination. We owe them much gratitude as well.

SP: It became clear to me that not only did I not know very much about bhikkhunis, but many people who identified as Buddhist didn’t know very much either. Much of first years was spent educating myself about bhikkhunis and their history and current achievements as well as challenges. I took multiple trips to Thailand. On one trip I went on a tour of different bhikkhuni monasteries there. I also went with Carol Annable, one of AfB’s most illustrious and hard-working vice presidents, to Sri Lanka and met quite a few women over there. Sri Lanka is way ahead of Thailand, and way ahead of Burma when it comes to ordaining bhikkhunis and supporting them. The Sri Lankan monks have been very pro-bhikkhunis, and have been tremendous leaders in helping women ordain. Australian bhikkhus have also been champions of bhikkhuni ordination. We owe them much gratitude as well.

I think in some ways, in many ways, Southeast Asian women have a much easier time ordaining than Western women. There is more practical support as well as emotional support coming from their Buddhist cultures. Southeast Asian women can travel to Sri Lanka to ordain. In Thailand, as women like Venerable Dhammananda will be in robes for ten years or longer, they can ordain other women in Thailand. It’s just must easier. It’s staggering financially for Western women to create a monastery due to the cost of land, construction costs, zoning about the type of structure and how many unrelated individuals can live in a building, and building code compliance, such as complying with the American Disabilities Act. All of that tends to be a big burden on a small community of women. In Thailand, four or five women can live together, it’s not a problem, but in a lot of places in the U.S., if you have more than three unrelated people they can’t live in a home together without the risk of neighbors filing a complaint. Plus a religious community wouldn’t want to violate local statutes.

BA: So, were some of the early projects more associated with establishing monasteries and improving the quality of them?

SP: Yes, money was sent to different places in Thailand, Sri Lanka, and the U.S. The AfB continues to respond to various funding requests in the U.S. as well as internationally. Aware of the need for education, we started a library, and eventually added the magazine Present which was initially a newsletter. Marcia Pimentel, who later ordained as a bhikkhuni, and Brenda Batke-Hirschmann, who later ordained as a samaneri, did a stunning job of transforming Present. I remain grateful to them. Present became a vehicle to educate people about current developments in the Bhikkhuni Sangha as well as providing scholarship on bhikkhuni history.

SP: Yes, money was sent to different places in Thailand, Sri Lanka, and the U.S. The AfB continues to respond to various funding requests in the U.S. as well as internationally. Aware of the need for education, we started a library, and eventually added the magazine Present which was initially a newsletter. Marcia Pimentel, who later ordained as a bhikkhuni, and Brenda Batke-Hirschmann, who later ordained as a samaneri, did a stunning job of transforming Present. I remain grateful to them. Present became a vehicle to educate people about current developments in the Bhikkhuni Sangha as well as providing scholarship on bhikkhuni history.

When I was introduced to bhikkhunis in Thailand, I learned of the erroneous but long-held belief perpetuated by bhikkhus that the Bhikkhuni Sangha had died out and could not be revived. Thoughtful, scholarly articles by Bhikkhu Bodhi and Ven. Anaalayo, among others, which were published in our Library and in Present, dispelled those misconceptions. The information coming from the AfB affected not only Southeast Asian women but Western women as well. At Amaravati Monastery in the UK, monastic women there, believing they could not become bhikkhunis, chose instead to become siladharas, a monastic community of women founded by Ajahn Sumedho. The work of AfB impacted the siladaras and prompted many of them to ordain as bhikkhunis later.

I also wrote articles for Present and gave papers at conferences in the U.S. and at Sakyadhita on the problems facing Western bhikkhunis. I also organized speaking tours by bhikkhunis who introduced American meditators to bhikkhunis for the first time.

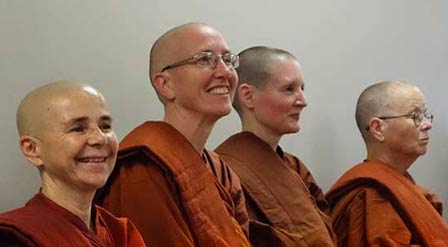

Susan is second from the left, in pink (to the far right is Tenzin Palmo and to her right is Bhikkhuni Ven. Dhammananda)

BA: I wasn’t in the Buddhist sphere ten years ago, so I don’t know what the attitudes surrounding bhikkhuni ordination were compared to what they are now. From what it seems like now, there still is a lot of non-education concerning the role of bhikkhunis or whether the lineage can be established. I’m thinking specifically of Thailand and even in the Thai sanghas in the west. So, what do you think the most effective way of educating about bhikkhuni ordination is? Has that changed over the years for you?

SP: When I was doing a tour of bhikkhuni monasteries in Thailand, I went on pindabat, alms round, with a few bhikkhunis in a remote village in Northern Thailand. People would rush out of their homes in the morning, so thrilled to give whatever food or rice they had, and would kneel and listen to the bhikkhunis chant. I found Thai people more accepting of bhikkhunis once they got to meet them. I have found some American Thais unable to accept the legitimacy and power of the Bhikkhuni Sangha. I was with Ayya Tathaaloka, this was about ten years ago, when we visited a Thai temple in Fremont, California where we met three professional Thai women. They were very convinced that men were superior because of their physical strength and other attributes. Even though they were very fluent in English, educated, and bright, they still aspired to be reborn as men. They didn’t see themselves as being capable, because of their gender, of becoming fully awake.

BA: Do you think that having the AfB as an organization has helped educate? There is the International Bhikkhuni Day, in which the primary goal is to educate people each year on bhikkhunis and bhikkhuni ordination. Do you think those efforts have helped spread awareness about bhikkhuni ordination?

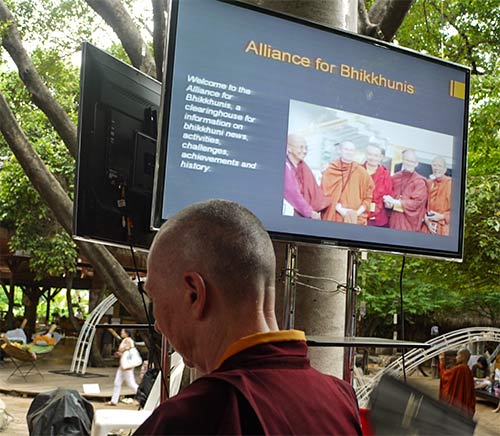

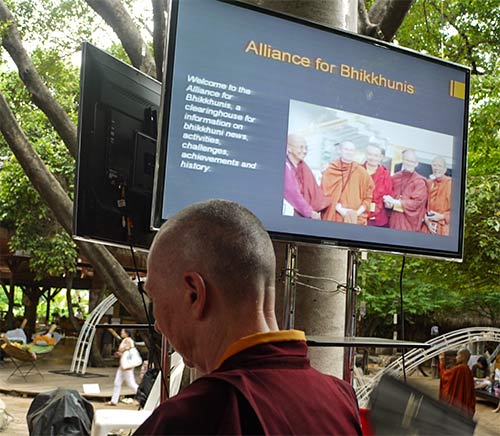

This photo shows a slide of the PowerPoint presentation that Susan gave at a maechee monastery in Thailand. Multiple large screens were placed around this monastery so everyone could see the slides.

SP: I think it has and continues to do that. Each year, articles on bhikkhunis dating from the time of the Buddha to the present are written. So I think it’s a gradual expansion of awareness and understanding. Younger people worldwide may more easily embrace the validity of bhikkhuni ordination as well as the value of having women monastics as teachers and advisers. During my trips to Thailand, many women confided that they much preferred discussing their family and marital problems with bhikkhunis. Laywomen could be more honest and vulnerable with bhikkhunis. Things they could not easily talk to a bhikkhu about, such as domestic violence or sexual assault, they could disclose to a bhikkhuni. In Southeast Asia where there continues to be a large sex trade as well as human trafficking, a Bhikkhuni Sangha presence can be a refuge and protection for women.

BA: This question kind of goes along with that. From a different perspective, how do you think the Bhikkhuni Sangha has changed during the last ten years? There are definitely more bhikkhunis than there were ten years ago, but aside from that, is there anything you’ve observed that’s really changed?

SP: Yes, there are many more bhikkhunis since the mid-1990’s when women began ordaining. I expect the number of bhikkhunis in Southeast Asia will grow. More male monks are not ordaining or are disrobing. There is a shrinking population of bhikkhus so I think women will be taking over much of the monastic tradition as well as exercising greater leadership in the dissemination and protection of the Dhamma. I think bhikkhunis have wonderful practices, and I think they are excellent teachers.

With the introduction of public education in Thailand, men don’t have the need to take robes to become educated. Decades ago in Thai villages, village viharas were the primary way boys became educated.

One thing that probably has not changed as a significant concern is healthcare. Western bhikkhuni monasteries would check on the health status of a woman and determine whether she could pay for her health coverage prior to consider admitting her. There are other considerations, of course. A sick samaneri or bhikkhuni could bankrupt a monastery. Before the Affordable Care Act, it was just astronomical, especially if a woman had health problems and wanted to ordain. There was some wariness about a woman’s motivation to ordain because in parts of Asia, when women didn’t have a husband and had health problems, they would sometimes opt to ordain just as a way of getting access to health care. So there were, and still are, concerns around housing and adequate health coverage.

Bhikkhunis also felt isolated in small viharas. They could not easily leave because their support, including assistance with medical expenses, was provided by their supporters. That funding would evaporate if they left. Women became monastics to be part of a community, yet they often found themselves quite isolated and lonely, and really struggling. AfB paid some medical costs as well as travel expenses just so bhikkhunis could spend the Rains Retreat together, and not just live in isolation. Going back to zoning, unless a monastery is zoned as a monastery, women can’t chant the patimokkha every two weeks and live in community as the Buddha intended. So, there were many practical obstacles in the West in the recent past, and I’m sure many of those have not been overcome.

BA: There are many different bhikkhuni monasteries, specifically in the U.S. and Canada, that are not all together, they’re all sort of scattered throughout. Why do you think, as opposed to in Asia where a monastery is fairly condensed, why do you think in the west there is that need to spread out?

SP: From a practical point of view, housing that can legally accommodate four or more unrelated women is an issue. When I met Ayya Tathaaloka, the people who were supporting her were renting a condo where zoning did not allow four unrelated women to live there at the same time. In addition, the small number of senior bhikkhunis limits the choices ordaining women have. It is not unusual for a man to study with many bhikkhus before deciding on a particular teacher and making a five-year commitment to train under that teacher. There is an emotionally intimate relationship between a monastic and a novice. Finding the right person usually takes some time.

At this time I don’t know how many [ordained] women there are in the United States. I could have given you that number five years ago.

BA: Do you think that establishing monasteries where women can live together in larger numbers relies on the financial support they receive?

Dhammadharini’s newly purchased land. Read more >>

SP: I think so. I think that’s a big piece of it. Bhikkhunis might have to look at solutions that might not be entirely appealing. Tracts of land or repurposed sites, such as old churches or schools, in remote areas may be more affordable and have the advantage of already being zoned as non-residential property. The tradeoff would be limited access to laypeople. Without lay supporters, bhikkhunis would find it problematic maintaining monastic vows.

BA: Sort of branching off of that, what do you think the needs are for the bhikkhunis today, as maybe opposed to when they organization first started? How have the needs evolved?

SP: I feel that I’m not the person to answer that. I would ask bhikkhunis and samaneris what their needs are. Just as a footnote to this, when I was in Sri Lanka, we visited a monastery in Horana, where women were preparing to ordain. There were perhaps ten to twelve samaneris, maybe more, who had been there for months, preparing for ordination. Some of the women were from Malaysia, others from Thailand. I was again struck by how intelligent ordaining bhikkhunis are. This is another footnote to my footnote. All the women I met had college degrees, many had graduate degrees. I’ve met bhikkhuni doctors and professors. The ordaining women are exceptionally talented, motivated, and versatile and have strong leadership skills. They are the future of the Bhikkhuni Sangha which tells me the Bhikkhuni Sangha has a promising future. This is a blessing for all of us. The best and the brightest are consistently coming forward.

One Malaysian samaneri I met at Horana was going back to Northern Thailand, to continue working with her primary teacher who was a bhikkhu. Her plan was to go back and just disappear for ten to fifteen years and focus on her practice. She saw herself as very young, and even though educated and intellectually knowledgeable about the Dhamma, she understood she needed much more training and spiritual practice. And so she had the luxury of being able to focus exclusively on her spiritual development. Sadly, this isn’t the case for many Western bhikkhunis who are obliged to travel and give Dharma talks very early in their monastic career as a way to fund their viharas. They lack the luxury of flying below the radar for ten or twenty years until they feel competent to teach.

BA: I guess I hadn’t really thought about that, because the bhikkhunis are maybe less supported than the bhikkhus, they are more obligated to do things to receive support for their communities rather than just being able to practice.

SP: Right. So, there’s a different kind of pressure or stress because of that. And a lot of the contacts that they form (I’m talking about Western bhikkhunis) are over the internet and via emails. Just to survive, they need to maintain a donor base, rather than having the gift of time to work on their practice.

BA: So, do you think that the need to support bhikkhunis over the last ten years has grown? It’s obviously very important, but do you think there’s become a greater need to support women who have ordained?

SP: I think for U.S. Theravada bhikkhunis the need is as great as it was ten years ago. For a variety of reasons, I don’t think the dynamic has changed very much. As I was preparing for this wonderful interview with you, (It’s very kind of you to do this interview!) I checked on religious demographic data. In Thailand, the country is 90-95% Buddhist. The remaining population is largely Muslim and Christian, but in the United States, the percentage of the population that identifies as Buddhist is about 2%, and some of those people are in different traditions, not just Theravada. Additionally, individuals may be born into Buddhist families but may not be practicing Buddhists themselves. As a result, a small segment of the U.S. population is asked to support male and female monastics. I expect this is the same in other Western countries whereas in Thailand, the government provides so much for the bhikkhus which reduces the amount laypeople must provide. The Thai population had a deeply entrenched tradition of supporting monks. In most cases, this has easily translated to support for bhikkhunis who are so obviously in need of help. In other monastic Buddhist traditions, the women have supported themselves through teaching or being hospital chaplains. Theravada bhikkhunis are precluded from employment, from handling money. There were, for example, other women who ordained with Ayya Khema, and they disrobed because they didn’t have financial or other support. Returning to meeting those three newly-ordained Thai bhikkhunis I encountered in 2006, I was dismayed by their circumstances. I just assumed everyone was like Ayya Khema, but they’re not. They don’t write books, they’re not charismatic, they’re not good teachers. So, many women have had to disrobe because of the lack of support. And I think that still goes on.

SP: I think for U.S. Theravada bhikkhunis the need is as great as it was ten years ago. For a variety of reasons, I don’t think the dynamic has changed very much. As I was preparing for this wonderful interview with you, (It’s very kind of you to do this interview!) I checked on religious demographic data. In Thailand, the country is 90-95% Buddhist. The remaining population is largely Muslim and Christian, but in the United States, the percentage of the population that identifies as Buddhist is about 2%, and some of those people are in different traditions, not just Theravada. Additionally, individuals may be born into Buddhist families but may not be practicing Buddhists themselves. As a result, a small segment of the U.S. population is asked to support male and female monastics. I expect this is the same in other Western countries whereas in Thailand, the government provides so much for the bhikkhus which reduces the amount laypeople must provide. The Thai population had a deeply entrenched tradition of supporting monks. In most cases, this has easily translated to support for bhikkhunis who are so obviously in need of help. In other monastic Buddhist traditions, the women have supported themselves through teaching or being hospital chaplains. Theravada bhikkhunis are precluded from employment, from handling money. There were, for example, other women who ordained with Ayya Khema, and they disrobed because they didn’t have financial or other support. Returning to meeting those three newly-ordained Thai bhikkhunis I encountered in 2006, I was dismayed by their circumstances. I just assumed everyone was like Ayya Khema, but they’re not. They don’t write books, they’re not charismatic, they’re not good teachers. So, many women have had to disrobe because of the lack of support. And I think that still goes on.

BA: To go on to our last question, what do you think the future of the Alliance for Bhikkhunis is in providing methods of support to bhikkhunis?

SP: I want to go back to what you asked me earlier about what were the challenges in the early days of the AfB. Something just magically came together. I think it was quite karmic somehow. But what I found harder was sustaining the AfB because when you have a volunteer-based organization, and people come and go, much work falls to a few. Volunteer organizations are stressful to sustain. One of the casualties was the magazine Present* there simply weren’t enough talented hands on deck to get the magazine out. At some point, I think it would be helpful for AfB to have funding for a skeletal staff to keep the organization operating as volunteers and board members come and go. I think AfB’s contributions to the Bhikkhuni Sangha are unique and the organization itself is deserving of support and funding for those reasons. The AfB was structured to be inclusive, and not tied to any one bhikkhuni or monastery. This makes it a valuable tool for bhikkhunis around the world who want to learn what their sisters are doing elsewhere. The AfB can do things a small vihara cannot do, such as fund an expanding online Library, among other resources.

If the AfB is still present ten, twenty or fifty years from now, I hope it is the go-to place to learn about bhikkhuni history and accomplishments as well as documenting the expanding role of the Bhikkhuni Sangha. I also hope the AfB provides teachings and Dhamma talks from bhikkhunis around the globe while simultaneously offering information on how people can access the bhikkhunis who especially speak to them. Through the AfB site, lay people can discover bhikkhuni monasteries at which to meditate or train for ordination. AfB has played a role in helping women ordain by assisting with travel and other expenses. This remains a critical endeavor as is assisting with the creation and repair of bhikkhuni monasteries. I hope men and women are inspired by the material on the AfB site and come to fully comprehend the vital and indispensable role the Bhikkhuni Sangha plays in fulfilling the Buddha’s creation of the Fourfold Sangha.

BA: To follow up, I’m trying to get at more of what the future of the AfB is pertaining to the specific needs of the bhikkhunis. What’s happening right now is that the AfB acts as an intermediary between the bhikkhunis and the lay-people, so if they don’t want to donate to one specific monastery, they can donate to the general fund, and that can be dispersed according to what the needs are at the time. Do you see that expanding into a role in which the AfB can really provide a very large amount of support to the bhikkhunis? We are providing support right now, but in a smaller role, with smaller needs.

SP: When I began the AfB, I thought of it as a fundraising organization; initially it was just for the Thai bhikkhunis. But as I really understood the extent of the lack of information about bhikkhunis, my ideas changed. In my own evolution, I came to see the AfB as an educational, religious non-profit that also funded monasteries and helped individual bhikkhunis. What makes the AfB unique? A small monastery would be not be able to maintain the extent of the centralized resources the AfB has and continues to expand upon. A monastery of five or six women could not keep abreast of the latest bhikkhuni scholarship or the political, social or other challenges faced by bhikkhunis.

When I was with the AfB, a Burmese bhikkhuni had gone to Burma to visit her father who was dying. The Burmese council of monks oppose bhikkhunis, and so when she landed in the country she was arrested and she was put in a Burmese jail. These Burmese jails are not like our jails. They are very extreme, very unpleasant places. She was not allowed to leave until she signed a paper saying she wasn’t a bhikkhuni and was forced to disrobe. After we published that story in Present, that was the end of women being in jailed in Burma. The Burmese monks do not like adverse publicity. We reported what the bhikkhus were doing in Southeast Asia and elsewhere. Shining a light on unacceptable practices is something a larger organization can do.

Reconstruction of bhikkhunis’ monastic lodgings in Sri Lanka

From the standpoint of looking at specific needs, the AfB could contribute to the construction of new bhikkhuni monasteries, possibly in more rural areas where there may be less financial support.

BA: You talk a lot about education, do you think there’s a need for more bhikkhuni scholars at a higher level? Right now there’s really, only that I can think of, Ayya Dhammadinna (Venerable Analayo’s student) who is a bhikkhuni in Taiwan, who is publishing and has a PhD, and is actively publishing in the scholarly field. There are really not many others who publish at that level.

SP: I don’t think it’s necessary for bhikkhunis to be scholars, but it is important for AfB to have open exchanges with academicians and scholars. I found scholars very helpful and generous with their time, people like Susanne Mrozik and Emma Tomalin. It is helpful for AfB to send representative to international conferences to stay informed and pass on what they learn to their readers.

In closing, I’d like to pass along a bit of AfB trivia. When I was trying to find a name for our newsletter, Ayya Sobhana and Ayya Sudhamma suggested the name Present. The Bhikkhuni Sangha was with us now, it was present, and was a gift or present to us all, as well as a prompt to remember to be mindful and present.

Brenna Artinger is a board member of the Alliance for Bhikkhunis. She has a Bachelor’s Degree in Literature from American University, and is currently traveling the world visiting Buddhist monasteries. In her free time she enjoys hiking and learning the Dhamma.

Brenna Artinger is a board member of the Alliance for Bhikkhunis. She has a Bachelor’s Degree in Literature from American University, and is currently traveling the world visiting Buddhist monasteries. In her free time she enjoys hiking and learning the Dhamma.

* This online issue of Present was published in 2016 as a commerative issue for the 2600th Anniversary of the Bhikkhuni Sangha. We are posting new articles periodically.

Header photo: Sopaporn Kurz

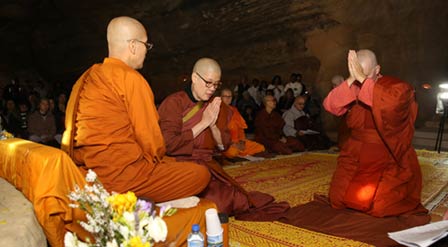

Photo taken at the Hamburg Congress in 2007, which was called by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. This conference, entitled, “The First International Congress of Buddhist Women’s Role in the Sangha” brought the issue of full ordination for women to world attention. Leading Buddhist monastics met to discuss the history and legitimacy of the ordination of women.

Pictured, left to right: Burmese Bhikkhuni Ven. Gunasari (retired physician); American Ven. Sobhana from Bhavana Society; British-born Ven. Tenzin Palmo (Cave in the Snow); American Ayya Tathaaloka, abbess of Dhammadharini; Ven. Dhammananda, first Thai bhikkhuni, renowned scholar.

Brenna Artinger (BA): Would you mind telling me a little bit about your background, how you got into Buddhism, and your meditation practice (specifically with teachers such as Ayya Khema)?

Susan Pembroke

Susan Pembroke (SP): I became introduced to Buddhism in the mid-1980s while I was living in Los Angeles, and I went to a center there called Community Meditation Center, which was founded and run by Shinzen Young, and at that time by his wife, Shelly Young. That was really classic, traditional Vipassana practice, and I did that for five or six years. I had the good fortune of sitting with a lot of meditation teachers who came to Los Angeles, people who were in all different traditions; I did a lot of one-day, and weekend, and week retreats. I also sat and did retreats in the Goenka tradition, and [retreats with] different monks who came through. I had the good fortune to do a long-weekend retreat with Robert Hover who studied with U Ba Khin, and so I also became very interested in [body] sweeping. I do jhanas, vipassana, body-sweeping, very traditional vipassana meditation and metta practices. I came across a book by Ayya Khema in the early 1990s and it was a book on the jhanas, among other subjects, and I found it very helpful. I had had an experience of jhana when I was around twelve years old, and I didn’t know what had happened to me; I was born and raised Catholic. So it was was very interesting, and wonderful, and scary at the same time. So when I read her description of jhana I thought, ‘Oh, this is what happened to me,’ and I was able to sit retreats with her when she traveled to the United States.

BA: What were your inspirations and motivations behind founding the Alliance for Bhikkhunis? What needs were you responding to at the time? It’s been 10 years since the AfB was founded, and bhikkhuni ordination (or the revival of bhikkhuni ordination) was fairly new at that time. What were the needs that inspired you to create the organization?

Ayya Khema

SP: I had travelled to Kuala Lumpur to attend the Sakyadhita conference there. I had an interest in Sakyadhita for a number of years because Ayya Khema was one of the founders of Sakyadhita. She was really an advocate for women monastics, and that organization obviously was, and continues to be, very helpful in advocating for monastics. So I just simply went with the desire to be with other Buddhist women and [to learn]. And I met at that time three Thai bhikkhunis who had just been ordained months before in Ayutthaya, which is an old Buddhist site in Thailand, with wonderful ancient ruins and temples. They really did it off the radar. It is banned still to ordain bhikkhunis in Thailand. And the people who ordained them were Mahayana bhikkshus and bhikkshunis. I struck up a conversation and friendship with them. They seemed so oppressed to me at that time. There were only four bhikkhunis in Thailand at the time: Ayya Dhammananda (who is very well known, she lives outside of Bangkok), who went to Sri Lanka to ordain; and then these three women who were very vulnerable, without support. I work as a psychotherapist, they just looked clinically depressed to me, and really even frightened for their safety. And so I said to them, ‘I’ll help you,’ not even really knowing what that meant. And I just wanted to send them some money, not a lot, $5,000-10,000 or something, so that they could get some land so they could start a monastery. The male monks there had tremendous support and all kinds of grants, and free education, and healthcare, and they just really had nothing. Then once I got home I realized, I can’t just raise money and send it there, I have to start a non-profit. So, that’s how the Alliance for Bhikkhunis started.

BA: Were the bhikkhunis that you were helping at the time mostly in Asia, in Thailand and Sri Lanka, was that the core of how it started? Was there a point when the organization spread West to the U.S. and Europe?

SP: I really was just focusing on Thailand because I just assumed that women in other countries, especially Western countries, were fine. This is how little I knew at the time. When I began it, I asked a Ventura-based Sri Lankan monk, Bhante Sutadhara for suggestions. He said, ‘there is a woman in Northern California who is a bhikkhuni’. He was talking about Ayya Tathaaloka, I didn’t know her. I just wrote to her out of the blue, and I went to visit her later that year, or early 2007. I learned what a tough time American women were having due to little or no organized support.

BA: To move on to the next question, what were some of the early challenges of starting a nonprofit? I can imagine it must have been fairly challenging to create this whole organization to support women. So what were some of the more specific needs that were challenging for getting the organization up and running?

SP: I really found that first part amazingly simple. People just appeared out of nowhere to help me, magically. A friend Michael Shiffman said, ‘this Mancuso book is a very good book for starting nonprofits.’ He had used it to start LA Dharma. Somebody who I meditated with said, ‘I know this attorney who starts nonprofits pro bono. Lucinda Green of Rocky Mountain Insight Colorado sent me the template that she used for starting a non-profit. Then, Ayya Tathaaloka somehow connected me to the Australian monk, Bhante Sujato, who said, ‘we have a monk here who will create a website for you.’ So everything was served up on a silver platter for me, and I just tapped some of my friends to be on the board. One of them is still on the board, Marsha Morrow. They just volunteered and helped. People have been extremely kind. Within a short amount of time it came together.

BA: That’s pretty amazing that is just all fell into place. For the earlier days of the organization, you mentioned how it started in Thailand as the inspiration for the organization. What were some of the early projects that were happening? What did those projects entail? If you could give us a couple of examples.

SP: It became clear to me that not only did I not know very much about bhikkhunis, but many people who identified as Buddhist didn’t know very much either. Much of first years was spent educating myself about bhikkhunis and their history and current achievements as well as challenges. I took multiple trips to Thailand. On one trip I went on a tour of different bhikkhuni monasteries there. I also went with Carol Annable, one of AfB’s most illustrious and hard-working vice presidents, to Sri Lanka and met quite a few women over there. Sri Lanka is way ahead of Thailand, and way ahead of Burma when it comes to ordaining bhikkhunis and supporting them. The Sri Lankan monks have been very pro-bhikkhunis, and have been tremendous leaders in helping women ordain. Australian bhikkhus have also been champions of bhikkhuni ordination. We owe them much gratitude as well.

SP: It became clear to me that not only did I not know very much about bhikkhunis, but many people who identified as Buddhist didn’t know very much either. Much of first years was spent educating myself about bhikkhunis and their history and current achievements as well as challenges. I took multiple trips to Thailand. On one trip I went on a tour of different bhikkhuni monasteries there. I also went with Carol Annable, one of AfB’s most illustrious and hard-working vice presidents, to Sri Lanka and met quite a few women over there. Sri Lanka is way ahead of Thailand, and way ahead of Burma when it comes to ordaining bhikkhunis and supporting them. The Sri Lankan monks have been very pro-bhikkhunis, and have been tremendous leaders in helping women ordain. Australian bhikkhus have also been champions of bhikkhuni ordination. We owe them much gratitude as well.

I think in some ways, in many ways, Southeast Asian women have a much easier time ordaining than Western women. There is more practical support as well as emotional support coming from their Buddhist cultures. Southeast Asian women can travel to Sri Lanka to ordain. In Thailand, as women like Venerable Dhammananda will be in robes for ten years or longer, they can ordain other women in Thailand. It’s just must easier. It’s staggering financially for Western women to create a monastery due to the cost of land, construction costs, zoning about the type of structure and how many unrelated individuals can live in a building, and building code compliance, such as complying with the American Disabilities Act. All of that tends to be a big burden on a small community of women. In Thailand, four or five women can live together, it’s not a problem, but in a lot of places in the U.S., if you have more than three unrelated people they can’t live in a home together without the risk of neighbors filing a complaint. Plus a religious community wouldn’t want to violate local statutes.

BA: So, were some of the early projects more associated with establishing monasteries and improving the quality of them?

SP: Yes, money was sent to different places in Thailand, Sri Lanka, and the U.S. The AfB continues to respond to various funding requests in the U.S. as well as internationally. Aware of the need for education, we started a library, and eventually added the magazine Present which was initially a newsletter. Marcia Pimentel, who later ordained as a bhikkhuni, and Brenda Batke-Hirschmann, who later ordained as a samaneri, did a stunning job of transforming Present. I remain grateful to them. Present became a vehicle to educate people about current developments in the Bhikkhuni Sangha as well as providing scholarship on bhikkhuni history.

SP: Yes, money was sent to different places in Thailand, Sri Lanka, and the U.S. The AfB continues to respond to various funding requests in the U.S. as well as internationally. Aware of the need for education, we started a library, and eventually added the magazine Present which was initially a newsletter. Marcia Pimentel, who later ordained as a bhikkhuni, and Brenda Batke-Hirschmann, who later ordained as a samaneri, did a stunning job of transforming Present. I remain grateful to them. Present became a vehicle to educate people about current developments in the Bhikkhuni Sangha as well as providing scholarship on bhikkhuni history.

When I was introduced to bhikkhunis in Thailand, I learned of the erroneous but long-held belief perpetuated by bhikkhus that the Bhikkhuni Sangha had died out and could not be revived. Thoughtful, scholarly articles by Bhikkhu Bodhi and Ven. Anaalayo, among others, which were published in our Library and in Present, dispelled those misconceptions. The information coming from the AfB affected not only Southeast Asian women but Western women as well. At Amaravati Monastery in the UK, monastic women there, believing they could not become bhikkhunis, chose instead to become siladharas, a monastic community of women founded by Ajahn Sumedho. The work of AfB impacted the siladaras and prompted many of them to ordain as bhikkhunis later.

I also wrote articles for Present and gave papers at conferences in the U.S. and at Sakyadhita on the problems facing Western bhikkhunis. I also organized speaking tours by bhikkhunis who introduced American meditators to bhikkhunis for the first time.

Susan is second from the left, in pink (to the far right is Tenzin Palmo and to her right is Bhikkhuni Ven. Dhammananda)

BA: I wasn’t in the Buddhist sphere ten years ago, so I don’t know what the attitudes surrounding bhikkhuni ordination were compared to what they are now. From what it seems like now, there still is a lot of non-education concerning the role of bhikkhunis or whether the lineage can be established. I’m thinking specifically of Thailand and even in the Thai sanghas in the west. So, what do you think the most effective way of educating about bhikkhuni ordination is? Has that changed over the years for you?

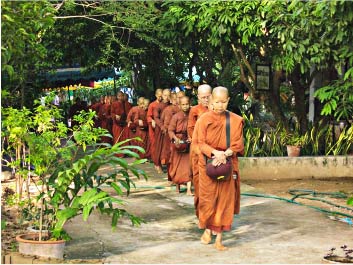

SP: When I was doing a tour of bhikkhuni monasteries in Thailand, I went on pindabat, alms round, with a few bhikkhunis in a remote village in Northern Thailand. People would rush out of their homes in the morning, so thrilled to give whatever food or rice they had, and would kneel and listen to the bhikkhunis chant. I found Thai people more accepting of bhikkhunis once they got to meet them. I have found some American Thais unable to accept the legitimacy and power of the Bhikkhuni Sangha. I was with Ayya Tathaaloka, this was about ten years ago, when we visited a Thai temple in Fremont, California where we met three professional Thai women. They were very convinced that men were superior because of their physical strength and other attributes. Even though they were very fluent in English, educated, and bright, they still aspired to be reborn as men. They didn’t see themselves as being capable, because of their gender, of becoming fully awake.

BA: Do you think that having the AfB as an organization has helped educate? There is the International Bhikkhuni Day, in which the primary goal is to educate people each year on bhikkhunis and bhikkhuni ordination. Do you think those efforts have helped spread awareness about bhikkhuni ordination?

This photo shows a slide of the PowerPoint presentation that Susan gave at a maechee monastery in Thailand. Multiple large screens were placed around this monastery so everyone could see the slides.

SP: I think it has and continues to do that. Each year, articles on bhikkhunis dating from the time of the Buddha to the present are written. So I think it’s a gradual expansion of awareness and understanding. Younger people worldwide may more easily embrace the validity of bhikkhuni ordination as well as the value of having women monastics as teachers and advisers. During my trips to Thailand, many women confided that they much preferred discussing their family and marital problems with bhikkhunis. Laywomen could be more honest and vulnerable with bhikkhunis. Things they could not easily talk to a bhikkhu about, such as domestic violence or sexual assault, they could disclose to a bhikkhuni. In Southeast Asia where there continues to be a large sex trade as well as human trafficking, a Bhikkhuni Sangha presence can be a refuge and protection for women.

BA: This question kind of goes along with that. From a different perspective, how do you think the Bhikkhuni Sangha has changed during the last ten years? There are definitely more bhikkhunis than there were ten years ago, but aside from that, is there anything you’ve observed that’s really changed?

SP: Yes, there are many more bhikkhunis since the mid-1990’s when women began ordaining. I expect the number of bhikkhunis in Southeast Asia will grow. More male monks are not ordaining or are disrobing. There is a shrinking population of bhikkhus so I think women will be taking over much of the monastic tradition as well as exercising greater leadership in the dissemination and protection of the Dhamma. I think bhikkhunis have wonderful practices, and I think they are excellent teachers.

With the introduction of public education in Thailand, men don’t have the need to take robes to become educated. Decades ago in Thai villages, village viharas were the primary way boys became educated.

One thing that probably has not changed as a significant concern is healthcare. Western bhikkhuni monasteries would check on the health status of a woman and determine whether she could pay for her health coverage prior to consider admitting her. There are other considerations, of course. A sick samaneri or bhikkhuni could bankrupt a monastery. Before the Affordable Care Act, it was just astronomical, especially if a woman had health problems and wanted to ordain. There was some wariness about a woman’s motivation to ordain because in parts of Asia, when women didn’t have a husband and had health problems, they would sometimes opt to ordain just as a way of getting access to health care. So there were, and still are, concerns around housing and adequate health coverage.

Bhikkhunis also felt isolated in small viharas. They could not easily leave because their support, including assistance with medical expenses, was provided by their supporters. That funding would evaporate if they left. Women became monastics to be part of a community, yet they often found themselves quite isolated and lonely, and really struggling. AfB paid some medical costs as well as travel expenses just so bhikkhunis could spend the Rains Retreat together, and not just live in isolation. Going back to zoning, unless a monastery is zoned as a monastery, women can’t chant the patimokkha every two weeks and live in community as the Buddha intended. So, there were many practical obstacles in the West in the recent past, and I’m sure many of those have not been overcome.

BA: There are many different bhikkhuni monasteries, specifically in the U.S. and Canada, that are not all together, they’re all sort of scattered throughout. Why do you think, as opposed to in Asia where a monastery is fairly condensed, why do you think in the west there is that need to spread out?

SP: From a practical point of view, housing that can legally accommodate four or more unrelated women is an issue. When I met Ayya Tathaaloka, the people who were supporting her were renting a condo where zoning did not allow four unrelated women to live there at the same time. In addition, the small number of senior bhikkhunis limits the choices ordaining women have. It is not unusual for a man to study with many bhikkhus before deciding on a particular teacher and making a five-year commitment to train under that teacher. There is an emotionally intimate relationship between a monastic and a novice. Finding the right person usually takes some time.

At this time I don’t know how many [ordained] women there are in the United States. I could have given you that number five years ago.

BA: Do you think that establishing monasteries where women can live together in larger numbers relies on the financial support they receive?

Dhammadharini’s newly purchased land. Read more >>

SP: I think so. I think that’s a big piece of it. Bhikkhunis might have to look at solutions that might not be entirely appealing. Tracts of land or repurposed sites, such as old churches or schools, in remote areas may be more affordable and have the advantage of already being zoned as non-residential property. The tradeoff would be limited access to laypeople. Without lay supporters, bhikkhunis would find it problematic maintaining monastic vows.

BA: Sort of branching off of that, what do you think the needs are for the bhikkhunis today, as maybe opposed to when they organization first started? How have the needs evolved?

SP: I feel that I’m not the person to answer that. I would ask bhikkhunis and samaneris what their needs are. Just as a footnote to this, when I was in Sri Lanka, we visited a monastery in Horana, where women were preparing to ordain. There were perhaps ten to twelve samaneris, maybe more, who had been there for months, preparing for ordination. Some of the women were from Malaysia, others from Thailand. I was again struck by how intelligent ordaining bhikkhunis are. This is another footnote to my footnote. All the women I met had college degrees, many had graduate degrees. I’ve met bhikkhuni doctors and professors. The ordaining women are exceptionally talented, motivated, and versatile and have strong leadership skills. They are the future of the Bhikkhuni Sangha which tells me the Bhikkhuni Sangha has a promising future. This is a blessing for all of us. The best and the brightest are consistently coming forward.

One Malaysian samaneri I met at Horana was going back to Northern Thailand, to continue working with her primary teacher who was a bhikkhu. Her plan was to go back and just disappear for ten to fifteen years and focus on her practice. She saw herself as very young, and even though educated and intellectually knowledgeable about the Dhamma, she understood she needed much more training and spiritual practice. And so she had the luxury of being able to focus exclusively on her spiritual development. Sadly, this isn’t the case for many Western bhikkhunis who are obliged to travel and give Dharma talks very early in their monastic career as a way to fund their viharas. They lack the luxury of flying below the radar for ten or twenty years until they feel competent to teach.

BA: I guess I hadn’t really thought about that, because the bhikkhunis are maybe less supported than the bhikkhus, they are more obligated to do things to receive support for their communities rather than just being able to practice.

SP: Right. So, there’s a different kind of pressure or stress because of that. And a lot of the contacts that they form (I’m talking about Western bhikkhunis) are over the internet and via emails. Just to survive, they need to maintain a donor base, rather than having the gift of time to work on their practice.

BA: So, do you think that the need to support bhikkhunis over the last ten years has grown? It’s obviously very important, but do you think there’s become a greater need to support women who have ordained?

SP: I think for U.S. Theravada bhikkhunis the need is as great as it was ten years ago. For a variety of reasons, I don’t think the dynamic has changed very much. As I was preparing for this wonderful interview with you, (It’s very kind of you to do this interview!) I checked on religious demographic data. In Thailand, the country is 90-95% Buddhist. The remaining population is largely Muslim and Christian, but in the United States, the percentage of the population that identifies as Buddhist is about 2%, and some of those people are in different traditions, not just Theravada. Additionally, individuals may be born into Buddhist families but may not be practicing Buddhists themselves. As a result, a small segment of the U.S. population is asked to support male and female monastics. I expect this is the same in other Western countries whereas in Thailand, the government provides so much for the bhikkhus which reduces the amount laypeople must provide. The Thai population had a deeply entrenched tradition of supporting monks. In most cases, this has easily translated to support for bhikkhunis who are so obviously in need of help. In other monastic Buddhist traditions, the women have supported themselves through teaching or being hospital chaplains. Theravada bhikkhunis are precluded from employment, from handling money. There were, for example, other women who ordained with Ayya Khema, and they disrobed because they didn’t have financial or other support. Returning to meeting those three newly-ordained Thai bhikkhunis I encountered in 2006, I was dismayed by their circumstances. I just assumed everyone was like Ayya Khema, but they’re not. They don’t write books, they’re not charismatic, they’re not good teachers. So, many women have had to disrobe because of the lack of support. And I think that still goes on.

SP: I think for U.S. Theravada bhikkhunis the need is as great as it was ten years ago. For a variety of reasons, I don’t think the dynamic has changed very much. As I was preparing for this wonderful interview with you, (It’s very kind of you to do this interview!) I checked on religious demographic data. In Thailand, the country is 90-95% Buddhist. The remaining population is largely Muslim and Christian, but in the United States, the percentage of the population that identifies as Buddhist is about 2%, and some of those people are in different traditions, not just Theravada. Additionally, individuals may be born into Buddhist families but may not be practicing Buddhists themselves. As a result, a small segment of the U.S. population is asked to support male and female monastics. I expect this is the same in other Western countries whereas in Thailand, the government provides so much for the bhikkhus which reduces the amount laypeople must provide. The Thai population had a deeply entrenched tradition of supporting monks. In most cases, this has easily translated to support for bhikkhunis who are so obviously in need of help. In other monastic Buddhist traditions, the women have supported themselves through teaching or being hospital chaplains. Theravada bhikkhunis are precluded from employment, from handling money. There were, for example, other women who ordained with Ayya Khema, and they disrobed because they didn’t have financial or other support. Returning to meeting those three newly-ordained Thai bhikkhunis I encountered in 2006, I was dismayed by their circumstances. I just assumed everyone was like Ayya Khema, but they’re not. They don’t write books, they’re not charismatic, they’re not good teachers. So, many women have had to disrobe because of the lack of support. And I think that still goes on.

BA: To go on to our last question, what do you think the future of the Alliance for Bhikkhunis is in providing methods of support to bhikkhunis?

SP: I want to go back to what you asked me earlier about what were the challenges in the early days of the AfB. Something just magically came together. I think it was quite karmic somehow. But what I found harder was sustaining the AfB because when you have a volunteer-based organization, and people come and go, much work falls to a few. Volunteer organizations are stressful to sustain. One of the casualties was the magazine Present* there simply weren’t enough talented hands on deck to get the magazine out. At some point, I think it would be helpful for AfB to have funding for a skeletal staff to keep the organization operating as volunteers and board members come and go. I think AfB’s contributions to the Bhikkhuni Sangha are unique and the organization itself is deserving of support and funding for those reasons. The AfB was structured to be inclusive, and not tied to any one bhikkhuni or monastery. This makes it a valuable tool for bhikkhunis around the world who want to learn what their sisters are doing elsewhere. The AfB can do things a small vihara cannot do, such as fund an expanding online Library, among other resources.

If the AfB is still present ten, twenty or fifty years from now, I hope it is the go-to place to learn about bhikkhuni history and accomplishments as well as documenting the expanding role of the Bhikkhuni Sangha. I also hope the AfB provides teachings and Dhamma talks from bhikkhunis around the globe while simultaneously offering information on how people can access the bhikkhunis who especially speak to them. Through the AfB site, lay people can discover bhikkhuni monasteries at which to meditate or train for ordination. AfB has played a role in helping women ordain by assisting with travel and other expenses. This remains a critical endeavor as is assisting with the creation and repair of bhikkhuni monasteries. I hope men and women are inspired by the material on the AfB site and come to fully comprehend the vital and indispensable role the Bhikkhuni Sangha plays in fulfilling the Buddha’s creation of the Fourfold Sangha.

BA: To follow up, I’m trying to get at more of what the future of the AfB is pertaining to the specific needs of the bhikkhunis. What’s happening right now is that the AfB acts as an intermediary between the bhikkhunis and the lay-people, so if they don’t want to donate to one specific monastery, they can donate to the general fund, and that can be dispersed according to what the needs are at the time. Do you see that expanding into a role in which the AfB can really provide a very large amount of support to the bhikkhunis? We are providing support right now, but in a smaller role, with smaller needs.

SP: When I began the AfB, I thought of it as a fundraising organization; initially it was just for the Thai bhikkhunis. But as I really understood the extent of the lack of information about bhikkhunis, my ideas changed. In my own evolution, I came to see the AfB as an educational, religious non-profit that also funded monasteries and helped individual bhikkhunis. What makes the AfB unique? A small monastery would be not be able to maintain the extent of the centralized resources the AfB has and continues to expand upon. A monastery of five or six women could not keep abreast of the latest bhikkhuni scholarship or the political, social or other challenges faced by bhikkhunis.

When I was with the AfB, a Burmese bhikkhuni had gone to Burma to visit her father who was dying. The Burmese council of monks oppose bhikkhunis, and so when she landed in the country she was arrested and she was put in a Burmese jail. These Burmese jails are not like our jails. They are very extreme, very unpleasant places. She was not allowed to leave until she signed a paper saying she wasn’t a bhikkhuni and was forced to disrobe. After we published that story in Present, that was the end of women being in jailed in Burma. The Burmese monks do not like adverse publicity. We reported what the bhikkhus were doing in Southeast Asia and elsewhere. Shining a light on unacceptable practices is something a larger organization can do.

Reconstruction of bhikkhunis’ monastic lodgings in Sri Lanka

From the standpoint of looking at specific needs, the AfB could contribute to the construction of new bhikkhuni monasteries, possibly in more rural areas where there may be less financial support.

BA: You talk a lot about education, do you think there’s a need for more bhikkhuni scholars at a higher level? Right now there’s really, only that I can think of, Ayya Dhammadinna (Venerable Analayo’s student) who is a bhikkhuni in Taiwan, who is publishing and has a PhD, and is actively publishing in the scholarly field. There are really not many others who publish at that level.

SP: I don’t think it’s necessary for bhikkhunis to be scholars, but it is important for AfB to have open exchanges with academicians and scholars. I found scholars very helpful and generous with their time, people like Susanne Mrozik and Emma Tomalin. It is helpful for AfB to send representative to international conferences to stay informed and pass on what they learn to their readers.

In closing, I’d like to pass along a bit of AfB trivia. When I was trying to find a name for our newsletter, Ayya Sobhana and Ayya Sudhamma suggested the name Present. The Bhikkhuni Sangha was with us now, it was present, and was a gift or present to us all, as well as a prompt to remember to be mindful and present.

Brenna Artinger is a board member of the Alliance for Bhikkhunis. She has a Bachelor’s Degree in Literature from American University, and is currently traveling the world visiting Buddhist monasteries. In her free time she enjoys hiking and learning the Dhamma.

Brenna Artinger is a board member of the Alliance for Bhikkhunis. She has a Bachelor’s Degree in Literature from American University, and is currently traveling the world visiting Buddhist monasteries. In her free time she enjoys hiking and learning the Dhamma.

* This online issue of Present was published in 2016 as a commerative issue for the 2600th Anniversary of the Bhikkhuni Sangha. We are posting new articles periodically.

Header photo: Sopaporn Kurz

Photo taken at the Hamburg Congress in 2007, which was called by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. This conference, entitled, “The First International Congress of Buddhist Women’s Role in the Sangha” brought the issue of full ordination for women to world attention. Leading Buddhist monastics met to discuss the history and legitimacy of the ordination of women.

Pictured, left to right: Burmese Bhikkhuni Ven. Gunasari (retired physician); American Ven. Sobhana from Bhavana Society; British-born Ven. Tenzin Palmo (Cave in the Snow); American Ayya Tathaaloka, abbess of Dhammadharini; Ven. Dhammananda, first Thai bhikkhuni, renowned scholar.

DONATE!

Visit our Anniversary Campaign page for check mailing info and to track how we are progressing towards our goal