A Sima of Flowers

An Interview with Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta

by Donna McCarthy

A Sima of Flowers

An Interview with

Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta

by Donna McCarthy

From the Winter 2012 edition of Present. For an update on the changes at Aloka Vihara since this was written, visit Saranaloka.org.

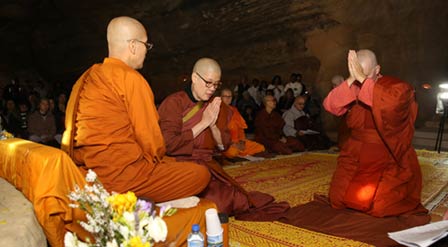

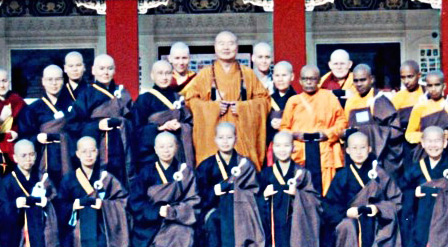

The dew was still wet on the grass, but the sun was beginning to take the chill out of the morning air. Three deer grazed their breakfast on the hill beyond the Meditation Hall. At Spirit Rock, on the morning of October 17, 2011, about 350 friends, supporters, staff and teachers from Spirit Rock, as well as over fifty monastics from Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana traditions gathered at the Meditation Hall to celebrate an historic event. On this auspicious day three Buddhist monastic women, samaneri, were about to be fully ordained as bhikkhunis in the Theravada tradition.

Significance of the Ordination

The event was historic because bhikkhuni ordinations, although prevalent during the time of the Buddha, had died out in the Theravada tradition some 1000 years ago and are only recently beginning to be revived. All of the noted speakers addressed this in their talks:

When they tried to fulfill their dream, they must have found it strange to be told that the doors were locked and the key had long ago vanished, that we must wait for the next Buddha to bring it back thousands of years in the future

Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi

“Today we witness a truly historic occasion, along with the other very recent Theravada Bhikkhuni ordinations in Sri Lanka, Australia, Northern California, and most courageously, those that have happened in Thailand. For over 1,000 years Theravada Bhikkhuni ordination has not been possible. But today, we are seeing the re-emergence of the full and proper place for female mendicants within the Holy Sasana of the Buddha. It’s been a long, long wait.” From the closing address given at the ordination by Thanissara, Dharmagiri Buddhist Hermitage, South Africa, Buddhist teacher and former Siladhara nun.

Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi said, “For Sisters Ānandabodhi and Santacittā, in particular, the road has been hard. When they tried to fulfill their dream, they must have found it strange to be told that the doors were locked and the key had long ago vanished, that we must wait for the next Buddha to bring it back thousands of years in the future.”

And Venerable Bhikkhu Analayo, in his talk on the ordination said, “The revival of the bhikkhunī tradition is, in my personal view, the most significant development for the Theravāda tradition of the 21st century….. Today’s event is another step in this direction, namely the revival of a full Buddhist community of four assemblies by reviving the bhikkhuni sangha.”

Although there have been several smaller bhikkhuni ordinations in this tradition in the past few years, this was one of the first ordinations that truly had the feeling of being ‘mainstream’, not only in its location at Spirit Rock, but in the wide support, both active and passive, of Theravada monks.

The Bhikkhuni Candidates

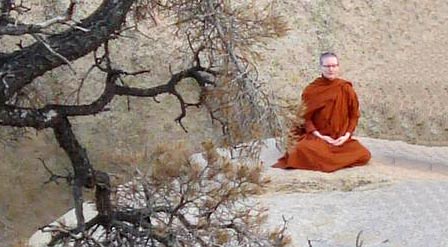

Ayya Anandabodhi was born in Wales in 1968. She first came across the Buddha’s teaching on the Four Noble Truths at the age of fourteen and felt a deep confidence that the Buddha knew the way out of suffering. She has practiced meditation since 1989 and lived in Amaravati and Chithurst monasteries in the UK from 1992 until 2009, training with the community of siladharas under the guidance of Ajahn Sumedho and Ajahn Sucitto.

Ayya Anandabodhi was born in Wales in 1968. She first came across the Buddha’s teaching on the Four Noble Truths at the age of fourteen and felt a deep confidence that the Buddha knew the way out of suffering. She has practiced meditation since 1989 and lived in Amaravati and Chithurst monasteries in the UK from 1992 until 2009, training with the community of siladharas under the guidance of Ajahn Sumedho and Ajahn Sucitto.

In 2009, she moved to the US at the invitation of the Saranaloka Foundation to help establish Aloka Vihara, a Theravada Buddhist monastic residence for women. Ayya Anandabodhi currently resides at Aloka Vihara and offers teachings at the Vihara as well as in the wider Bay Area and occasionally in other parts of the US. The example and teachings of Ajahn Chah continue to be a source of inspiration and guidance in her life and practice.

Ayya Santacitta was born in Austria in 1958 and has practiced meditation for over twenty years. After graduating in hotel management, she studied cultural anthropology and worked in avant-garde dance theatre as a performer and costume designer.

Ayya Santacitta was born in Austria in 1958 and has practiced meditation for over twenty years. After graduating in hotel management, she studied cultural anthropology and worked in avant-garde dance theatre as a performer and costume designer.

Her first teacher was Ajahn Buddhadasa, whom she met in 1988 and who sparked her interest in Buddhist monastic life. She has trained as a nun in both the East and West since 1993, primarily with the siladhara community at Amaravati Monastery under the guidance of Ajahn Sumedho. Since 2002, she also integrates Dzogchen teachings of the Vajrayana into her practice.

Ayya Santacitta is co-founder of Aloka Vihara, where she has lived since 2009. She offers teachings at the Vihara, as well as in the wider Bay Area and occasionally other parts of the US, sharing her experience in community as a means for cultivating the heart and opening the mind.

Ayya Nimmala, a native of Canada, was a steward and in training at Theravada Buddhist monasteries in Canada for five years prior to this ordination. She became an anagarika in 2008 and then took samaneri ordination in 2010, both at Sati Saraniya Hermitage, with Ayya Medhanandi as preceptor. She is currently training at Sati Saraniya Hermitage and is a member of that community in Perth, Ontario, headed by Abbess Ayya Medhanandi Bhikkhuni. Ayya Medhanandi was also a siladhara nun in the UK with Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta before she ordained as a bhikkhuni in Taiwan.

Ayya Nimmala, a native of Canada, was a steward and in training at Theravada Buddhist monasteries in Canada for five years prior to this ordination. She became an anagarika in 2008 and then took samaneri ordination in 2010, both at Sati Saraniya Hermitage, with Ayya Medhanandi as preceptor. She is currently training at Sati Saraniya Hermitage and is a member of that community in Perth, Ontario, headed by Abbess Ayya Medhanandi Bhikkhuni. Ayya Medhanandi was also a siladhara nun in the UK with Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta before she ordained as a bhikkhuni in Taiwan.

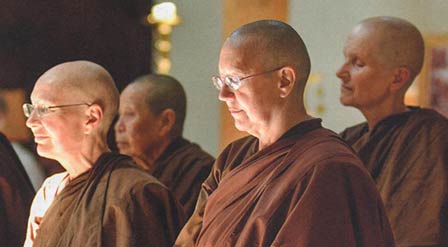

Brief Background of the Theravada Tradition and the Siladhara Path

Historically, in Thailand, the only monastic option for Buddhist women was that of a mae chee, eight-precept nun. In 1979, at Chithurst Buddhist Monastery in the UK, a branch monastery in the Thai Forest Tradition of Ajahn Chah, a group of four women requested and received permission from the abbot, Ajahn Sumedho, to become mae chee. After four years, the eight precepts did not provide an appropriate training and the lay community asked that the nuns be given a higher ordination. Ajahn Sumedho requested and received permission from the Thai Sangha for them to take ten precepts, relinquishing the handling of money, cooking and driving. They began wearing dark brown robes to distinguish them from the saffron robes of the monks. Thus the siladhara nun’s order was established.

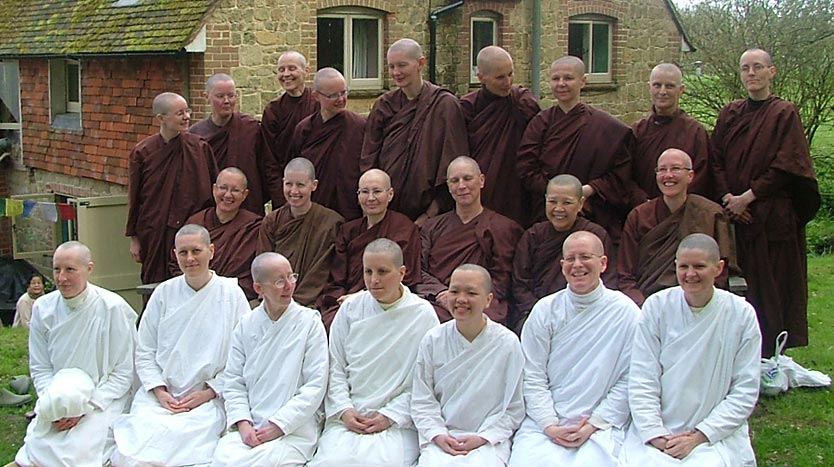

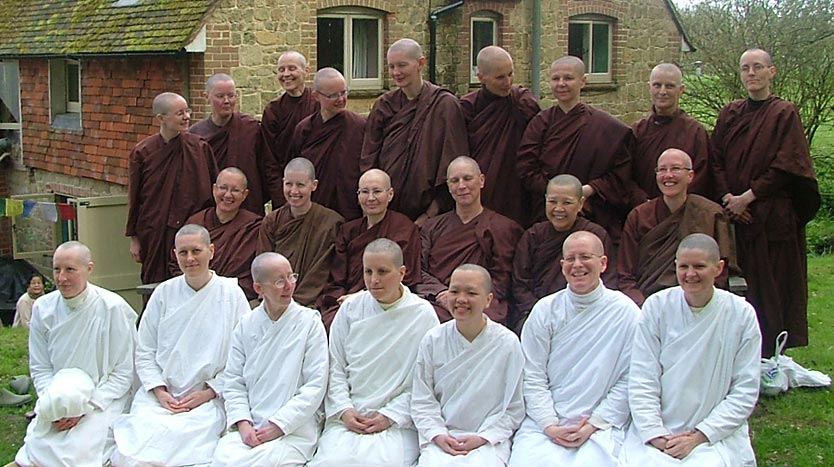

Siladhara Ten Precept Nuns Order – UK

When Ajahn Sumedho took this step to create the siladhara order, it was a radical development giving the nuns an opportunity to be alms mendicants, an opportunity that was not available to them in Thailand. The siladhara order began to grow and gave many women an opportunity to train. These communities at Amaravati and Chithurst were very successful in terms of excellence of training and forming a cohesive nuns’ community.

Thanissara explains, “Since then, in the English monasteries of the Forest Sangha of Ajahn Chah, where Ayya Anandabodhi, Ayya Santacitta, and Ayya Nimmala’s teacher— Ayya Medhanandi—trained, there have been forty-four siladhara who have ordained over the last, nearly thirty, years. The siladhara, who are categorized as ten-precept nuns, actually lived and still live as bhikkhunis, in all but legal status.”

Subsequently, several of senior siladhara, Venerables Medhanandi, Thanasanti, and now Anandabodhi and Santacitta, wishing to pass on full ordination for future generations of women, have chosen to follow the bhikkhuni path. Their past struggles, and their courage, have “broken trail” for others who wish to follow. One might say of Ayya Nimmala that she enjoys the first fruit of their struggle.

Leave Taking

In order to take full ordination Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta formally “took leave” of the siladhara community and the Ajahn Chah Lineage, which does not offer the option of full ordination for women. In fact, bhikkhuni ordination was specifically prohibited by the “Five Points.”1

In April of 2011, in announcing their intention to take leave of their order and become bhikkhunis, the nuns wrote: “Since our arrival here last December, we recognize more and more the impact on our hearts of those five points and the vulnerability of the siladhara ordination, which is valid only in the Ajahn Chah/Ajahn Sumedho lineage. The ready availability in the U.S. of bhikkhuni ordination offers us a new platform for the establishment of a training monastery for women. Taking all these things into consideration, we have come to the decision to move towards taking bhikkhuni ordination to provide a stronger container to pass on to other women.”

Can you describe your “leave taking” from the Ajahn Chah lineage; what was that experience like? Were there any places where you felt fear but went ahead?

Ayya Anandabodhi: The nuns received us with warmth and respect and it was very touching to see them again, having been through so much together over the years and knowing that we were meeting in order to part. I appreciated the leave taking ceremony. The whole of the siladhara community and four senior bhikkhus were present and sat encircling us as we took leave. I felt there was an honoring of what we have given to the community over the years. The leave taking ceremony was an opportunity for us to acknowledge what we have received there and to ask forgiveness for any harm we may have caused others and to offer forgiveness in return. It felt empowering to be able to so clearly state my intention to leave in order to continue my practice as a Theravadan bhikkhuni. I appreciated the dignity and kindness within which the ceremony was held.

The bhikkhuni ordination is…the beginning step of establishing a training monastery for women.

Jill Boone

I can’t say I experienced fear during the process of leaving. I could not have ignored the call to take bhikkhuni ordination, any more than I could have ignored the calling to enter monastic life in the first place. The whole process seems to have been held within a greater intention than my own.

Ayya Santacitta: The leave taking at Amaravati went very well. For sure, the siladhara sisters were very supportive and helped to make the ceremony a kind and heartfelt one. We stayed for one week at Amaravati and had time to say “goodbye” individually and also as a group. We were given blessings by the monks and the nuns and a lovely departure with a rose petal shower and chanting. There was no fear and it all felt very clear, actually I really did not feel that there was another option for me. The only other options beside bhikkhuni ordination would have been to become a wandering ten-precept nun or to disrobe.

Since my first days in Ajahn Buddhadasa’s monastery in Thailand, I felt called to help set up a monastery for women. That was in the early 90s. It has taken a long time for this intention to start ripening and in 2009 I followed Saranaloka’s invitation to come to the Bay Area in order to help with setting up a training monastery.

And Finally, The Ordination

The morning started with the meal offering. Two long rows of tables set up in front of the dining hall overflowed with food offerings.

Following the meal the lay women and laymen lined the path way to the Meditation Hall and scattered flower petals in front of the feet of the monastics as they processed into the Hall. View video of this procession

Flowered Bhikkhuni Ordination Sima Marker

In the center of the meditation hall a ‘sima’ had been established. A sima is a boundary within which the monastic sangha’s formal acts must be performed in order to be valid. At a monastery, monastics will gather within the sima to recite the patimokkha (the basic rules and regulations of the order) or to hold sacred ceremonies such as ordinations. The sima boundary is delineated by sima markers, in Thailand they are often carved from stone.

When visiting a monastery in Northeast Thailand, I was shown the old moss and lichen-covered stone sima markers. I found myself wondering what the bhikkhuni sima markers would be like. My mouth fell open when I saw tall stands topped with bouquets of flowers and leaves cascading over the sides, holding the sima stones.

With the monastics seated within the sima, lay women and men, and other witnessing monastics took their seats in circles around the sima. Jack Kornfield welcomed everyone to Spirit Rock Meditation Center.

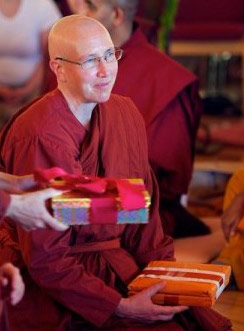

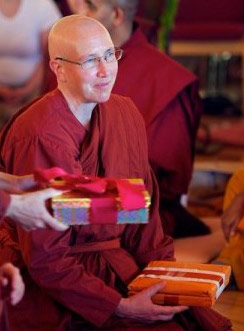

Ayya Tathaaloka Theri

Ayya Tathaaloka Theri, the pavattini (preceptor), explained that each of the candidates would be requesting their upasampada (full ordination) by an act of the Dual Sangha.

The candidates would first be ordained by a quorum of Theravada bhikkhunis, led by Ayya Tathaaloka Theri, and then confirmed by a quorum of Theravada bhikkhus, led by Bhante Pallewela Rahula Mahathera as the ovadakacariya or confirming bhikkhu.

The ceremony was followed by congratulatory addresses and talks by prominent monastics and Buddhist teachers. Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi was unable to attend because of poor health, but in his recorded congratulatory message talked about his study of Buddhist texts, and that “if we start with different premises from the traditionalists, we could reach a different conclusion. We could conclude that bhikkhuni ordination for Theravada women is valid, and given this fact, we could claim that there are no legal barriers against such ordinations.”

Venerable Anaalayo reflected on the importance of bhikkhunis in the time of the Buddha, the negative attitudes toward them that arose after that time and the importance of the revival of the bhikkhuni order. This was followed by ‘Words of Blessing’ from Ruth Denison and a brief ‘Sharing the Vision’ by Jill Boone, President of Saranaloka Foundation. Thanissara (formerly a Siladhara) gave a moving closing address reflecting on the struggles that have been endured in order for this event to happen.

At the conclusion of the ceremony, lay people were able to congratulate the new bhikkhunis and present gifts. Gratitude was expressed to Mindy Zlotnick and volunteers for their impressive organization of the event.

The Future

In her concluding remarks Jill Boone talked about the future: “The bhikkhuni ordination is both a deep personal commitment and an auspicious, historical moment for women in Buddhism. It is also the beginning step of establishing a training monastery for women. We hope, within the next year, to be able to acquire rural property near San Francisco, for Ayya Santacitta and Ayya Anandabodhi to move to in order to create a monastery where both men and women can visit for short periods to participate in the community and where women can stay for longer periods to reflect on whether they want to pursue monastic life. It is with great joy that I am experiencing this moment of transition and opening.”

Questions and Answers

We wondered about the process and influences that propelled the two women who had been siladhara for so many years along the path to becoming bhikkhunis.

What first drew you to Buddhism? Why did you feel called to become a monastic? What things factored into your decision first to ordain as an anagarika?

Ayya Santacitta: On trips to Burma and Thailand in the late 80s I saw Buddhist monastics and temples and felt deeply struck by a peaceful presence, but I also had less inspiring experiences with particularly one monk. I lived for more than a year at Wat Suan Mokkh, the temple of my first teacher Ajahn Buddhadasa and felt ‘called’ to ordain, but the situation of the Thai nuns (mae chee) did not feel very inspiring or promising. I needed to be with Westerners and travelled to Amaravati in the UK to see how that would be. After a few months I became an anagarika there.

Ayya Anandabodhi: I first came across Buddhism in my early teens through a book while seeking to learn to meditate. Although much of the book was beyond my grasp, as I read about ‘the Four Noble Truths’ I felt an immediate resonance and a deep confidence that the Buddha knew the way out of suffering.

At the age of 20, on hearing that there were Buddhist monks living in Thailand, I knew deep in my heart that I wanted to be a Buddhist nun. Until that point I had no idea that Buddhist monastic path was still open, so it was a delight to hear that there were monks practicing and teaching in the world at that time. I just assumed that there must also be Buddhist nuns. A couple of years later I visited Amaravati Monastery and greatly benefited from the environment and teachings there. There were both monks and nuns living at Amaravati and although I was very aware of the discrepancy in the power structure between them, I assumed that over time, the form would naturally evolve to be appropriate to the western culture. I became torn between my lay life and the strong calling to monastic life. It was after the death of Ajahn Chah in 1992, that I decided to spend a year as an anagarika and see where that led.

Who were the main people who influenced your decision to ordain as a bhikkhuni and can you tell us about your own personal decision-making process in choosing to ordain as a bhikkhuni?

Ayya Anandabodhi: Attending the Hamburg Congress on Buddhist Women in 2007 began to open my perspective on bhikkhuni ordination. Until that time I had felt that the whole bhikkhuni issue was so fraught with difficulties that I was inclined to stay as a siladhara and live a quiet life. I had always heard that the obstacle to ordaining women in the Theravada tradition was a legal one – involving vinaya – which could not be changed. Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi’s excellent presentation at the conference broke down that myth, as he concluded that the obstacles to full ordination for women were social, cultural and political, but not legal. (Now published as “The Revival of Bhikkhuni Ordination in the Theravada Tradition”.)

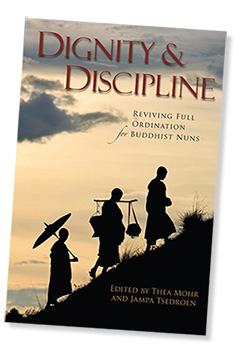

The incredible dedication of Venerable Jampa Tsedroen Bhikkhuni (author of “Dignity & Discipline – Reviving Full Ordination for Buddhist Nuns”), and her struggle to win equality for women in the monastic sangha, seemingly against all odds, also touched me deeply during the conference. However, I still had my doubts about the practicality of keeping the bhikkhuni vinaya in the 21st century and whether that was something I wanted to take on.

The incredible dedication of Venerable Jampa Tsedroen Bhikkhuni (author of “Dignity & Discipline – Reviving Full Ordination for Buddhist Nuns”), and her struggle to win equality for women in the monastic sangha, seemingly against all odds, also touched me deeply during the conference. However, I still had my doubts about the practicality of keeping the bhikkhuni vinaya in the 21st century and whether that was something I wanted to take on.

It was during a solitary retreat in May 2010 that I finally realized that bhikkhuni ordination was the only way forward if we were to establish a training monastery for women here in the US. Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi befriended our community around that time. His depth of knowledge and breadth of vision opened up new vistas of possibility for me.

I made investigations about taking full ordination with well established bhikkhuni sanghas in Sri Lanka, Korea and Taiwan. The problem I came across again and again was that they did not recognize our siladhara ordination and training as having any validity at all. Those who were open to giving ordination to western women required that we live for two years with them as samaneris (novices) and a further two years as bhikkhunis. This would be appropriate for women newly entering the monastic life, but did not take into account the 18 years of training we had already fulfilled. Taking ordination in one of these countries would have meant losing Aloka Vihara and the community that had built up around it. Fortunately, Ayya Tathaaloka Theri was open to discuss the possibility of giving us ordination. She recognized our siladhara ordination as a valid pabbajja (novice ordination) and respected our years of training. After some discussion, she agreed to be our bhikkhuni preceptor and brought together the key people needed to perform the ordination. This was a great gift.

Ayya Santacitta: For quite a long time I was not interested in bhikkhuni ordination, mainly because of the Eight Garudhammas and also because I had heard that the code of rules was impossible to hold. After coming to the Westcoast and looking into setting up a training monastery for women, it became clear that a ‘real’ ordination (bhikkhuni ordination) and equality of ordination status was needed as a strong basis to start building from. I felt unable and unwilling to pass on the ‘Five Points’, given to the Siladhara Order by the Monks’ Sangha of Amaravati/Chithurst monasteries in the UK.

After meeting Ven. Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo in India in 2005 and in ongoing correspondence after that, she was very clear in letting me know that she thought that bhikkhuni ordination is very important. In the Vajrayana tradition nuns cannot become geshe-ma (Dr of Divinity) if they cannot study the Vinaya, and they only can study the Vinaya if they are bhikkhunis. Reading papers from the Hamburg conference 2007 showed that bhikkhuni ordination was a possibility. In July 2010 a conversation with Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi cleared away last doubts for me and I felt ready to look for a way to receive bhikkhuni ordination.

What were some of the benefits of your siladhara training and how has that training helped you to travel along this bhikkhuni path? Has being a siladhara influenced how you wish to organize your bhikkhuni viharas? If so, how?

Ayya Santacitta: Living in a Western nuns’ community for 17 years (with interruptions when travelling to Asia) has been a great opportunity for learning about myself through the feedback of group living. In particular I have learned that keeping rules very tightly and strictly is not helpful. I also appreciate that therapeutic support was used by the Siladhara Order for group work and also for individuals if it was available.

Ayya Anandabodhi: I found great benefit in being part of a nuns’ community dedicated to monastic training, meditation and service. It is rare to find such a community in the West and I feel a deep gratitude for the years I spent with the nuns in England. The siladhara keep a high level of training very close to that of bhikkhunis. There are minor differences to my life now, but much less than I had anticipated. I feel the siladhara training has provided a sound basis from which to develop the bhikkhuni training here in the US.

The emphasis on meditation, monastic discipline and community are elements from the siladhara training that carry through to our vihara here. I feel it is important for women to have their own communities, not governed by the monks. I am happy to see several bhikkhuni viharas and hermitages being established in the US at this time and in other parts of the world.

What were some of the feelings that you experienced before and/or during the ceremony?

Ayya Anandabodhi: Approaching the ordination was like moving towards a threshold that we have been told for so long could not be crossed. There was no real knowing what was on the other side and there was no going back. As we drove across the Golden Gate Bridge on our way to Spirit Rock on that glorious sunny morning of October 17th, the thought came to me: “It’s a beautiful day to die!” with this I felt a great sense of joy and expansiveness.

Ayya Anandabodhi: Approaching the ordination was like moving towards a threshold that we have been told for so long could not be crossed. There was no real knowing what was on the other side and there was no going back. As we drove across the Golden Gate Bridge on our way to Spirit Rock on that glorious sunny morning of October 17th, the thought came to me: “It’s a beautiful day to die!” with this I felt a great sense of joy and expansiveness.

I was moved to see the incredible care and skill that people put in to making the ordination a beautiful event. So many people came to show their support and I delighted in seeing the many monastics from all schools of Buddhism come together to witness this full ordination.

Ayya Santacitta: Regarding the ordination itself I had no doubts. I felt that this was the right thing to do and needed to be done. It was amazing that all the right conditions had come together for the ordination ceremony to be held in such a loving and empowered space, with many friends and supporters present who came from as far as Austria, Germany, England and Australia.

What were some of the most poignant moments during the ceremony for you?

Ayya Santacitta: I really loved the procession so beautifully orchestrated by Ayya Tathaaloka Theri and also that the ordination sima was in the midst of circles of lay people. Having a female preceptor in the center of such a large ceremonial setting was something I had never seen before – I really had to stop and take that in deeply, so as to fully notice the difference and allow myself to feel the tenderness of a totally new perception.

I was very glad to have Thanissara there and loved her closing address. It was also powerful to witness how supportive the Sri Lankan monks were of our ordination – I was very touched by the kindness of the two witnessing monks as they chanted with so much heart.

Ayya Anandabodhi: Stepping into the sima boundary at the very beginning of the ceremony and requesting full ordination from Ayya Tathaaloka Theri and the bhikkhuni sangha was a poignant moment for me. I felt a lot of gratitude to the bhikkhunis for being there and for having opened the way.

Bhante Shantarasita and Bhante Amara Buddhi, both local Sri Lankan monks, chanted with such metta and mudita during the last part of the ordination, that I felt the stresses and struggles of my last years in England being washed away, bathed with this timeless devotion to the Triple Gem. The circles of friends and supporters surrounding the sima made a network of Dhamma practitioners, holding that sacred space. How rare for all these conditions to come together!

How does it feel now to be a bhikkhuni? How does ordaining as a bhikkhuni change things? How has or will your life as a bhikkhuni be different from your life as a siladhara?

Ayya Anandabodhi: It feels very natural to be a bhikkhuni. There are some small changes in our daily lives, but nothing that has felt very significant so far. The main difference is that I am now part of the pioneering bhikkhuni sangha, and that has a different energy to being part of a close-knit group in a well-established lineage.

Ayya Santacitta: I feel like I am out of a box and in a much bigger space. In terms of vinaya, the siladhara training is actually very close to bhikkhuni training; there are not many changes in daily life for me after bhikkhuni ordination. The biggest change for me is not being able to cut plants or pick flowers, as I love to take care of flower arrangements on our shrine. Another difference is living now in a small community of just 2–3 nuns and a lay steward; at Amaravati there were always about 50 people around. It is not easy to let go of the companionship of a whole circle of spiritual friends at the same time.

What advice would you give to a woman considering ordaining?

Ayya Santacitta: Do not look for the perfect monastery, as you will not be able to find it. Follow your heart’s intuition when looking for a place to ordain and work with what you find. The only thing you can really influence is keeping your intention clear and knowing why you want to ordain. Keep coming back to that intention everyday and take care of it.

Ayya Anandabodhi: Take the time to check out a few places and see what feels most resonant, but don’t get lost in an endless search for perfection. In the beginning, think of making a commitment for a year, rather than debating whether you can commit to being a nun for the rest of your life or not. Be willing to do the work that is required – both inner and outer.

Along with our congratulations, we extend much gratitude to Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta for their thoughtful responses to our questions.

To conclude, in thinking on the events of the day, we have to agree with the sentiments expressed by Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi:”In Pali there is a word that expresses what I’m feeling far better than the English word “congratulations.” This is the word anumodanā. The word means “rejoicing in unison,” that is, sharing the joy of those who directly experience joy. I know that today is a day of great joy for the three new bhikkhunis. It is also an occasion of anumodanā for me, and it must surely be a day of anumodanā for everyone present at their ordination.”

End Note

1“The Five Points” were given to the Siladhara Order in August 2009 as a requirement for them to remain part of the lineage of Ajahn Chah and Ajahn Sumedho.

- The structural relationship, as indicated by the Vinaya, of the Bhikkhu Sangha to the Siladhara Sangha is one of seniority, such that the most junior bhikkhu is “senior” to the most senior siladhara. As this relationship of seniority is defined by the Vinaya, it is not considered something we can change.

- In line with this, leadership in ritual situations where there are both bhikkhus and siladhara–such as giving the anumodana [blessings to the lay community] or precepts, leading the chanting or giving a talk–is presumed to rest with the senior bhikkhu present. He may invite a siladhara to lead; if this becomes a regular invitation it does not imply a new standard of shared leadership.

- The Bhikkhu Sangha will be responsible for the siladhara pabbajja [ordination] the way Luang Por Sumedho [Ajahn Sumedho] was in the past. The siladhara should look to the Bhikkhu Sangha for ordination and guidance rather than exclusively to Luang Por. A candidate for siladhara pabbajja should receive acceptance from the Siladhara Sangha, and should then receive approval by the Bhikkhu Sangha as represented by those

bhikkhus who sit on the Elders’ Council. - The formal ritual of giving pavarana [invitation for feedback] by the Siladhara Sangha to the Bhikkhu Sangha should take place at the end of the Vassa as it has in our communities traditionally, in keeping with the structure of the Vinaya

- The siladhara training is considered to be a vehicle fully suitable for the realization of liberation, and is respected as such within our tradition. It is offered as a complete training as it stands, and not as a step in the evolution towards a different form, such as bhikkhuni ordination.

About the Author

Photo Credits: Ordination photos by Ed Ritger

Siladhara photo courtesy of Aloka Vihara Monastery

From the Winter 2012 edition of Present. For an update on the changes at Aloka Vihara since this was written, visit Saranaloka.org.

The dew was still wet on the grass, but the sun was beginning to take the chill out of the morning air. Three deer grazed their breakfast on the hill beyond the Meditation Hall. At Spirit Rock, on the morning of October 17, 2011, about 350 friends, supporters, staff and teachers from Spirit Rock, as well as over fifty monastics from Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana traditions gathered at the Meditation Hall to celebrate an historic event. On this auspicious day three Buddhist monastic women, samaneri, were about to be fully ordained as bhikkhunis in the Theravada tradition.

Significance of the Ordination

The event was historic because bhikkhuni ordinations, although prevalent during the time of the Buddha, had died out in the Theravada tradition some 1000 years ago and are only recently beginning to be revived. All of the noted speakers addressed this in their talks:

When they tried to fulfill their dream, they must have found it strange to be told that the doors were locked and the key had long ago vanished, that we must wait for the next Buddha to bring it back thousands of years in the future

Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi

“Today we witness a truly historic occasion, along with the other very recent Theravada Bhikkhuni ordinations in Sri Lanka, Australia, Northern California, and most courageously, those that have happened in Thailand. For over 1,000 years Theravada Bhikkhuni ordination has not been possible. But today, we are seeing the re-emergence of the full and proper place for female mendicants within the Holy Sasana of the Buddha. It’s been a long, long wait.” From the closing address given at the ordination by Thanissara, Dharmagiri Buddhist Hermitage, South Africa, Buddhist teacher and former Siladhara nun.

Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi said, “For Sisters Ānandabodhi and Santacittā, in particular, the road has been hard. When they tried to fulfill their dream, they must have found it strange to be told that the doors were locked and the key had long ago vanished, that we must wait for the next Buddha to bring it back thousands of years in the future.”

And Venerable Bhikkhu Analayo, in his talk on the ordination said, “The revival of the bhikkhunī tradition is, in my personal view, the most significant development for the Theravāda tradition of the 21st century….. Today’s event is another step in this direction, namely the revival of a full Buddhist community of four assemblies by reviving the bhikkhuni sangha.”

Although there have been several smaller bhikkhuni ordinations in this tradition in the past few years, this was one of the first ordinations that truly had the feeling of being ‘mainstream’, not only in its location at Spirit Rock, but in the wide support, both active and passive, of Theravada monks.

The Bhikkhuni Candidates

Ayya Anandabodhi was born in Wales in 1968. She first came across the Buddha’s teaching on the Four Noble Truths at the age of fourteen and felt a deep confidence that the Buddha knew the way out of suffering. She has practiced meditation since 1989 and lived in Amaravati and Chithurst monasteries in the UK from 1992 until 2009, training with the community of siladharas under the guidance of Ajahn Sumedho and Ajahn Sucitto.

Ayya Anandabodhi was born in Wales in 1968. She first came across the Buddha’s teaching on the Four Noble Truths at the age of fourteen and felt a deep confidence that the Buddha knew the way out of suffering. She has practiced meditation since 1989 and lived in Amaravati and Chithurst monasteries in the UK from 1992 until 2009, training with the community of siladharas under the guidance of Ajahn Sumedho and Ajahn Sucitto.

In 2009, she moved to the US at the invitation of the Saranaloka Foundation to help establish Aloka Vihara, a Theravada Buddhist monastic residence for women. Ayya Anandabodhi currently resides at Aloka Vihara and offers teachings at the Vihara as well as in the wider Bay Area and occasionally in other parts of the US. The example and teachings of Ajahn Chah continue to be a source of inspiration and guidance in her life and practice.

Ayya Santacitta was born in Austria in 1958 and has practiced meditation for over twenty years. After graduating in hotel management, she studied cultural anthropology and worked in avant-garde dance theatre as a performer and costume designer.

Ayya Santacitta was born in Austria in 1958 and has practiced meditation for over twenty years. After graduating in hotel management, she studied cultural anthropology and worked in avant-garde dance theatre as a performer and costume designer.

Her first teacher was Ajahn Buddhadasa, whom she met in 1988 and who sparked her interest in Buddhist monastic life. She has trained as a nun in both the East and West since 1993, primarily with the siladhara community at Amaravati Monastery under the guidance of Ajahn Sumedho. Since 2002, she also integrates Dzogchen teachings of the Vajrayana into her practice.

Ayya Santacitta is co-founder of Aloka Vihara, where she has lived since 2009. She offers teachings at the Vihara, as well as in the wider Bay Area and occasionally other parts of the US, sharing her experience in community as a means for cultivating the heart and opening the mind.

Ayya Nimmala, a native of Canada, was a steward and in training at Theravada Buddhist monasteries in Canada for five years prior to this ordination. She became an anagarika in 2008 and then took samaneri ordination in 2010, both at Sati Saraniya Hermitage, with Ayya Medhanandi as preceptor. She is currently training at Sati Saraniya Hermitage and is a member of that community in Perth, Ontario, headed by Abbess Ayya Medhanandi Bhikkhuni. Ayya Medhanandi was also a siladhara nun in the UK with Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta before she ordained as a bhikkhuni in Taiwan.

Ayya Nimmala, a native of Canada, was a steward and in training at Theravada Buddhist monasteries in Canada for five years prior to this ordination. She became an anagarika in 2008 and then took samaneri ordination in 2010, both at Sati Saraniya Hermitage, with Ayya Medhanandi as preceptor. She is currently training at Sati Saraniya Hermitage and is a member of that community in Perth, Ontario, headed by Abbess Ayya Medhanandi Bhikkhuni. Ayya Medhanandi was also a siladhara nun in the UK with Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta before she ordained as a bhikkhuni in Taiwan.

Brief Background of the Theravada Tradition and the Siladhara Path

Historically, in Thailand, the only monastic option for Buddhist women was that of a mae chee, eight-precept nun. In 1979, at Chithurst Buddhist Monastery in the UK, a branch monastery in the Thai Forest Tradition of Ajahn Chah, a group of four women requested and received permission from the abbot, Ajahn Sumedho, to become mae chee. After four years, the eight precepts did not provide an appropriate training and the lay community asked that the nuns be given a higher ordination. Ajahn Sumedho requested and received permission from the Thai Sangha for them to take ten precepts, relinquishing the handling of money, cooking and driving. They began wearing dark brown robes to distinguish them from the saffron robes of the monks. Thus the siladhara nun’s order was established.

Siladhara Ten Precept Nuns Order – UK

When Ajahn Sumedho took this step to create the siladhara order, it was a radical development giving the nuns an opportunity to be alms mendicants, an opportunity that was not available to them in Thailand. The siladhara order began to grow and gave many women an opportunity to train. These communities at Amaravati and Chithurst were very successful in terms of excellence of training and forming a cohesive nuns’ community.

Thanissara explains, “Since then, in the English monasteries of the Forest Sangha of Ajahn Chah, where Ayya Anandabodhi, Ayya Santacitta, and Ayya Nimmala’s teacher— Ayya Medhanandi—trained, there have been forty-four siladhara who have ordained over the last, nearly thirty, years. The siladhara, who are categorized as ten-precept nuns, actually lived and still live as bhikkhunis, in all but legal status.”

Subsequently, several of senior siladhara, Venerables Medhanandi, Thanasanti, and now Anandabodhi and Santacitta, wishing to pass on full ordination for future generations of women, have chosen to follow the bhikkhuni path. Their past struggles, and their courage, have “broken trail” for others who wish to follow. One might say of Ayya Nimmala that she enjoys the first fruit of their struggle.

Leave Taking

In order to take full ordination Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta formally “took leave” of the siladhara community and the Ajahn Chah Lineage, which does not offer the option of full ordination for women. In fact, bhikkhuni ordination was specifically prohibited by the “Five Points.”1

In April of 2011, in announcing their intention to take leave of their order and become bhikkhunis, the nuns wrote: “Since our arrival here last December, we recognize more and more the impact on our hearts of those five points and the vulnerability of the siladhara ordination, which is valid only in the Ajahn Chah/Ajahn Sumedho lineage. The ready availability in the U.S. of bhikkhuni ordination offers us a new platform for the establishment of a training monastery for women. Taking all these things into consideration, we have come to the decision to move towards taking bhikkhuni ordination to provide a stronger container to pass on to other women.”

Can you describe your “leave taking” from the Ajahn Chah lineage; what was that experience like? Were there any places where you felt fear but went ahead?

Ayya Anandabodhi: The nuns received us with warmth and respect and it was very touching to see them again, having been through so much together over the years and knowing that we were meeting in order to part. I appreciated the leave taking ceremony. The whole of the siladhara community and four senior bhikkhus were present and sat encircling us as we took leave. I felt there was an honoring of what we have given to the community over the years. The leave taking ceremony was an opportunity for us to acknowledge what we have received there and to ask forgiveness for any harm we may have caused others and to offer forgiveness in return. It felt empowering to be able to so clearly state my intention to leave in order to continue my practice as a Theravadan bhikkhuni. I appreciated the dignity and kindness within which the ceremony was held.

The bhikkhuni ordination is…the beginning step of establishing a training monastery for women.

Jill Boone

I can’t say I experienced fear during the process of leaving. I could not have ignored the call to take bhikkhuni ordination, any more than I could have ignored the calling to enter monastic life in the first place. The whole process seems to have been held within a greater intention than my own.

Ayya Santacitta: The leave taking at Amaravati went very well. For sure, the siladhara sisters were very supportive and helped to make the ceremony a kind and heartfelt one. We stayed for one week at Amaravati and had time to say “goodbye” individually and also as a group. We were given blessings by the monks and the nuns and a lovely departure with a rose petal shower and chanting. There was no fear and it all felt very clear, actually I really did not feel that there was another option for me. The only other options beside bhikkhuni ordination would have been to become a wandering ten-precept nun or to disrobe.

Since my first days in Ajahn Buddhadasa’s monastery in Thailand, I felt called to help set up a monastery for women. That was in the early 90s. It has taken a long time for this intention to start ripening and in 2009 I followed Saranaloka’s invitation to come to the Bay Area in order to help with setting up a training monastery.

And Finally, The Ordination

The morning started with the meal offering. Two long rows of tables set up in front of the dining hall overflowed with food offerings.

Following the meal the lay women and laymen lined the path way to the Meditation Hall and scattered flower petals in front of the feet of the monastics as they processed into the Hall. View video of this procession

Flowered Bhikkhuni Ordination Sima Marker

In the center of the meditation hall a ‘sima’ had been established. A sima is a boundary within which the monastic sangha’s formal acts must be performed in order to be valid. At a monastery, monastics will gather within the sima to recite the patimokkha (the basic rules and regulations of the order) or to hold sacred ceremonies such as ordinations. The sima boundary is delineated by sima markers, in Thailand they are often carved from stone.

When visiting a monastery in Northeast Thailand, I was shown the old moss and lichen-covered stone sima markers. I found myself wondering what the bhikkhuni sima markers would be like. My mouth fell open when I saw tall stands topped with bouquets of flowers and leaves cascading over the sides, holding the sima stones.

With the monastics seated within the sima, lay women and men, and other witnessing monastics took their seats in circles around the sima. Jack Kornfield welcomed everyone to Spirit Rock Meditation Center.

Ayya Tathaaloka Theri

Ayya Tathaaloka Theri, the pavattini (preceptor), explained that each of the candidates would be requesting their upasampada (full ordination) by an act of the Dual Sangha.

The candidates would first be ordained by a quorum of Theravada bhikkhunis, led by Ayya Tathaaloka Theri, and then confirmed by a quorum of Theravada bhikkhus, led by Bhante Pallewela Rahula Mahathera as the ovadakacariya or confirming bhikkhu.

The ceremony was followed by congratulatory addresses and talks by prominent monastics and Buddhist teachers. Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi was unable to attend because of poor health, but in his recorded congratulatory message talked about his study of Buddhist texts, and that “if we start with different premises from the traditionalists, we could reach a different conclusion. We could conclude that bhikkhuni ordination for Theravada women is valid, and given this fact, we could claim that there are no legal barriers against such ordinations.”

Venerable Anaalayo reflected on the importance of bhikkhunis in the time of the Buddha, the negative attitudes toward them that arose after that time and the importance of the revival of the bhikkhuni order. This was followed by ‘Words of Blessing’ from Ruth Denison and a brief ‘Sharing the Vision’ by Jill Boone, President of Saranaloka Foundation. Thanissara (formerly a Siladhara) gave a moving closing address reflecting on the struggles that have been endured in order for this event to happen.

At the conclusion of the ceremony, lay people were able to congratulate the new bhikkhunis and present gifts. Gratitude was expressed to Mindy Zlotnick and volunteers for their impressive organization of the event.

The Future

In her concluding remarks Jill Boone talked about the future: “The bhikkhuni ordination is both a deep personal commitment and an auspicious, historical moment for women in Buddhism. It is also the beginning step of establishing a training monastery for women. We hope, within the next year, to be able to acquire rural property near San Francisco, for Ayya Santacitta and Ayya Anandabodhi to move to in order to create a monastery where both men and women can visit for short periods to participate in the community and where women can stay for longer periods to reflect on whether they want to pursue monastic life. It is with great joy that I am experiencing this moment of transition and opening.”

Questions and Answers

We wondered about the process and influences that propelled the two women who had been siladhara for so many years along the path to becoming bhikkhunis.

What first drew you to Buddhism? Why did you feel called to become a monastic? What things factored into your decision first to ordain as an anagarika?

Ayya Santacitta: On trips to Burma and Thailand in the late 80s I saw Buddhist monastics and temples and felt deeply struck by a peaceful presence, but I also had less inspiring experiences with particularly one monk. I lived for more than a year at Wat Suan Mokkh, the temple of my first teacher Ajahn Buddhadasa and felt ‘called’ to ordain, but the situation of the Thai nuns (mae chee) did not feel very inspiring or promising. I needed to be with Westerners and travelled to Amaravati in the UK to see how that would be. After a few months I became an anagarika there.

Ayya Anandabodhi: I first came across Buddhism in my early teens through a book while seeking to learn to meditate. Although much of the book was beyond my grasp, as I read about ‘the Four Noble Truths’ I felt an immediate resonance and a deep confidence that the Buddha knew the way out of suffering.

At the age of 20, on hearing that there were Buddhist monks living in Thailand, I knew deep in my heart that I wanted to be a Buddhist nun. Until that point I had no idea that Buddhist monastic path was still open, so it was a delight to hear that there were monks practicing and teaching in the world at that time. I just assumed that there must also be Buddhist nuns. A couple of years later I visited Amaravati Monastery and greatly benefited from the environment and teachings there. There were both monks and nuns living at Amaravati and although I was very aware of the discrepancy in the power structure between them, I assumed that over time, the form would naturally evolve to be appropriate to the western culture. I became torn between my lay life and the strong calling to monastic life. It was after the death of Ajahn Chah in 1992, that I decided to spend a year as an anagarika and see where that led.

Who were the main people who influenced your decision to ordain as a bhikkhuni and can you tell us about your own personal decision-making process in choosing to ordain as a bhikkhuni?

Ayya Anandabodhi: Attending the Hamburg Congress on Buddhist Women in 2007 began to open my perspective on bhikkhuni ordination. Until that time I had felt that the whole bhikkhuni issue was so fraught with difficulties that I was inclined to stay as a siladhara and live a quiet life. I had always heard that the obstacle to ordaining women in the Theravada tradition was a legal one – involving vinaya – which could not be changed. Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi’s excellent presentation at the conference broke down that myth, as he concluded that the obstacles to full ordination for women were social, cultural and political, but not legal. (Now published as “The Revival of Bhikkhuni Ordination in the Theravada Tradition”.)

The incredible dedication of Venerable Jampa Tsedroen Bhikkhuni (author of “Dignity & Discipline – Reviving Full Ordination for Buddhist Nuns”), and her struggle to win equality for women in the monastic sangha, seemingly against all odds, also touched me deeply during the conference. However, I still had my doubts about the practicality of keeping the bhikkhuni vinaya in the 21st century and whether that was something I wanted to take on.

The incredible dedication of Venerable Jampa Tsedroen Bhikkhuni (author of “Dignity & Discipline – Reviving Full Ordination for Buddhist Nuns”), and her struggle to win equality for women in the monastic sangha, seemingly against all odds, also touched me deeply during the conference. However, I still had my doubts about the practicality of keeping the bhikkhuni vinaya in the 21st century and whether that was something I wanted to take on.

It was during a solitary retreat in May 2010 that I finally realized that bhikkhuni ordination was the only way forward if we were to establish a training monastery for women here in the US. Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi befriended our community around that time. His depth of knowledge and breadth of vision opened up new vistas of possibility for me.

I made investigations about taking full ordination with well established bhikkhuni sanghas in Sri Lanka, Korea and Taiwan. The problem I came across again and again was that they did not recognize our siladhara ordination and training as having any validity at all. Those who were open to giving ordination to western women required that we live for two years with them as samaneris (novices) and a further two years as bhikkhunis. This would be appropriate for women newly entering the monastic life, but did not take into account the 18 years of training we had already fulfilled. Taking ordination in one of these countries would have meant losing Aloka Vihara and the community that had built up around it. Fortunately, Ayya Tathaaloka Theri was open to discuss the possibility of giving us ordination. She recognized our siladhara ordination as a valid pabbajja (novice ordination) and respected our years of training. After some discussion, she agreed to be our bhikkhuni preceptor and brought together the key people needed to perform the ordination. This was a great gift.

Ayya Santacitta: For quite a long time I was not interested in bhikkhuni ordination, mainly because of the Eight Garudhammas and also because I had heard that the code of rules was impossible to hold. After coming to the Westcoast and looking into setting up a training monastery for women, it became clear that a ‘real’ ordination (bhikkhuni ordination) and equality of ordination status was needed as a strong basis to start building from. I felt unable and unwilling to pass on the ‘Five Points’, given to the Siladhara Order by the Monks’ Sangha of Amaravati/Chithurst monasteries in the UK.

After meeting Ven. Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo in India in 2005 and in ongoing correspondence after that, she was very clear in letting me know that she thought that bhikkhuni ordination is very important. In the Vajrayana tradition nuns cannot become geshe-ma (Dr of Divinity) if they cannot study the Vinaya, and they only can study the Vinaya if they are bhikkhunis. Reading papers from the Hamburg conference 2007 showed that bhikkhuni ordination was a possibility. In July 2010 a conversation with Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi cleared away last doubts for me and I felt ready to look for a way to receive bhikkhuni ordination.

What were some of the benefits of your siladhara training and how has that training helped you to travel along this bhikkhuni path? Has being a siladhara influenced how you wish to organize your bhikkhuni viharas? If so, how?

Ayya Santacitta: Living in a Western nuns’ community for 17 years (with interruptions when travelling to Asia) has been a great opportunity for learning about myself through the feedback of group living. In particular I have learned that keeping rules very tightly and strictly is not helpful. I also appreciate that therapeutic support was used by the Siladhara Order for group work and also for individuals if it was available.

Ayya Anandabodhi: I found great benefit in being part of a nuns’ community dedicated to monastic training, meditation and service. It is rare to find such a community in the West and I feel a deep gratitude for the years I spent with the nuns in England. The siladhara keep a high level of training very close to that of bhikkhunis. There are minor differences to my life now, but much less than I had anticipated. I feel the siladhara training has provided a sound basis from which to develop the bhikkhuni training here in the US.

The emphasis on meditation, monastic discipline and community are elements from the siladhara training that carry through to our vihara here. I feel it is important for women to have their own communities, not governed by the monks. I am happy to see several bhikkhuni viharas and hermitages being established in the US at this time and in other parts of the world.

What were some of the feelings that you experienced before and/or during the ceremony?

Ayya Anandabodhi: Approaching the ordination was like moving towards a threshold that we have been told for so long could not be crossed. There was no real knowing what was on the other side and there was no going back. As we drove across the Golden Gate Bridge on our way to Spirit Rock on that glorious sunny morning of October 17th, the thought came to me: “It’s a beautiful day to die!” with this I felt a great sense of joy and expansiveness.

Ayya Anandabodhi: Approaching the ordination was like moving towards a threshold that we have been told for so long could not be crossed. There was no real knowing what was on the other side and there was no going back. As we drove across the Golden Gate Bridge on our way to Spirit Rock on that glorious sunny morning of October 17th, the thought came to me: “It’s a beautiful day to die!” with this I felt a great sense of joy and expansiveness.

I was moved to see the incredible care and skill that people put in to making the ordination a beautiful event. So many people came to show their support and I delighted in seeing the many monastics from all schools of Buddhism come together to witness this full ordination.

Ayya Santacitta: Regarding the ordination itself I had no doubts. I felt that this was the right thing to do and needed to be done. It was amazing that all the right conditions had come together for the ordination ceremony to be held in such a loving and empowered space, with many friends and supporters present who came from as far as Austria, Germany, England and Australia.

What were some of the most poignant moments during the ceremony for you?

Ayya Santacitta: I really loved the procession so beautifully orchestrated by Ayya Tathaaloka Theri and also that the ordination sima was in the midst of circles of lay people. Having a female preceptor in the center of such a large ceremonial setting was something I had never seen before – I really had to stop and take that in deeply, so as to fully notice the difference and allow myself to feel the tenderness of a totally new perception.

I was very glad to have Thanissara there and loved her closing address. It was also powerful to witness how supportive the Sri Lankan monks were of our ordination – I was very touched by the kindness of the two witnessing monks as they chanted with so much heart.

Ayya Anandabodhi: Stepping into the sima boundary at the very beginning of the ceremony and requesting full ordination from Ayya Tathaaloka Theri and the bhikkhuni sangha was a poignant moment for me. I felt a lot of gratitude to the bhikkhunis for being there and for having opened the way.

Bhante Shantarasita and Bhante Amara Buddhi, both local Sri Lankan monks, chanted with such metta and mudita during the last part of the ordination, that I felt the stresses and struggles of my last years in England being washed away, bathed with this timeless devotion to the Triple Gem. The circles of friends and supporters surrounding the sima made a network of Dhamma practitioners, holding that sacred space. How rare for all these conditions to come together!

How does it feel now to be a bhikkhuni? How does ordaining as a bhikkhuni change things? How has or will your life as a bhikkhuni be different from your life as a siladhara?

Ayya Anandabodhi: It feels very natural to be a bhikkhuni. There are some small changes in our daily lives, but nothing that has felt very significant so far. The main difference is that I am now part of the pioneering bhikkhuni sangha, and that has a different energy to being part of a close-knit group in a well-established lineage.

Ayya Santacitta: I feel like I am out of a box and in a much bigger space. In terms of vinaya, the siladhara training is actually very close to bhikkhuni training; there are not many changes in daily life for me after bhikkhuni ordination. The biggest change for me is not being able to cut plants or pick flowers, as I love to take care of flower arrangements on our shrine. Another difference is living now in a small community of just 2–3 nuns and a lay steward; at Amaravati there were always about 50 people around. It is not easy to let go of the companionship of a whole circle of spiritual friends at the same time.

What advice would you give to a woman considering ordaining?

Ayya Santacitta: Do not look for the perfect monastery, as you will not be able to find it. Follow your heart’s intuition when looking for a place to ordain and work with what you find. The only thing you can really influence is keeping your intention clear and knowing why you want to ordain. Keep coming back to that intention everyday and take care of it.

Ayya Anandabodhi: Take the time to check out a few places and see what feels most resonant, but don’t get lost in an endless search for perfection. In the beginning, think of making a commitment for a year, rather than debating whether you can commit to being a nun for the rest of your life or not. Be willing to do the work that is required – both inner and outer.

Along with our congratulations, we extend much gratitude to Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta for their thoughtful responses to our questions.

To conclude, in thinking on the events of the day, we have to agree with the sentiments expressed by Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi:”In Pali there is a word that expresses what I’m feeling far better than the English word “congratulations.” This is the word anumodanā. The word means “rejoicing in unison,” that is, sharing the joy of those who directly experience joy. I know that today is a day of great joy for the three new bhikkhunis. It is also an occasion of anumodanā for me, and it must surely be a day of anumodanā for everyone present at their ordination.”

End Note

1“The Five Points” were given to the Siladhara Order in August 2009 as a requirement for them to remain part of the lineage of Ajahn Chah and Ajahn Sumedho.

- The structural relationship, as indicated by the Vinaya, of the Bhikkhu Sangha to the Siladhara Sangha is one of seniority, such that the most junior bhikkhu is “senior” to the most senior siladhara. As this relationship of seniority is defined by the Vinaya, it is not considered something we can change.

- In line with this, leadership in ritual situations where there are both bhikkhus and siladhara–such as giving the anumodana [blessings to the lay community] or precepts, leading the chanting or giving a talk–is presumed to rest with the senior bhikkhu present. He may invite a siladhara to lead; if this becomes a regular invitation it does not imply a new standard of shared leadership.

- The Bhikkhu Sangha will be responsible for the siladhara pabbajja [ordination] the way Luang Por Sumedho [Ajahn Sumedho] was in the past. The siladhara should look to the Bhikkhu Sangha for ordination and guidance rather than exclusively to Luang Por. A candidate for siladhara pabbajja should receive acceptance from the Siladhara Sangha, and should then receive approval by the Bhikkhu Sangha as represented by those

bhikkhus who sit on the Elders’ Council. - The formal ritual of giving pavarana [invitation for feedback] by the Siladhara Sangha to the Bhikkhu Sangha should take place at the end of the Vassa as it has in our communities traditionally, in keeping with the structure of the Vinaya

- The siladhara training is considered to be a vehicle fully suitable for the realization of liberation, and is respected as such within our tradition. It is offered as a complete training as it stands, and not as a step in the evolution towards a different form, such as bhikkhuni ordination.

About the Author

Photo Credits: Ordination photos by Ed Ritger

Siladhara photo courtesy of Aloka Vihara Monastery