Book Review:

Stars at Dawn

by Wendy Garling

Review by Mary Grace Orr

Book Review:

Stars at Dawn

by Wendy Garling

Review by Mary Grace Orr

Book Review:

Stars at Dawn

by Wendy Garling

Review by Mary Grace Orr

There were women there. Really.

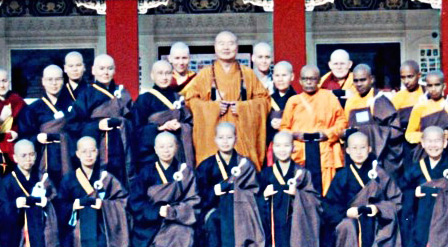

Most of us who have studied, practiced and read about Buddhism and the life of the Buddha have hardly noticed their presence. His life and time, and the subsequent thrust of his teachings have seemed overwhelmingly male and largely monastic. Although in his teachings he provided us with the model of the fourfold sangha (monks, nuns, lay men and lay women), the female half of that sangha has largely been ignored and held to a less significant place.

Wendy Garling’s book, Stars at Dawn, is a refreshing rejoinder to that picture. She reminds us in the beginning that the Buddha taught that, “all believers in his faith — women and men, lay and ordained, would become wise and accomplished through his teachings…” (p. 1)

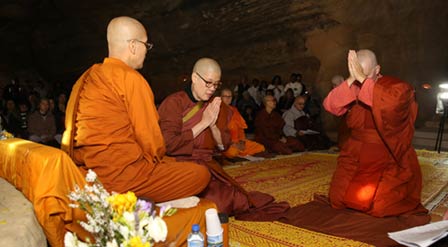

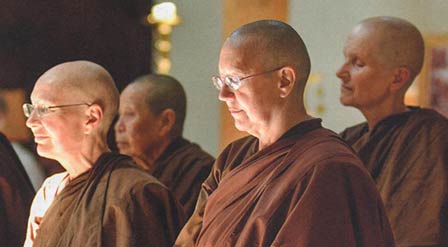

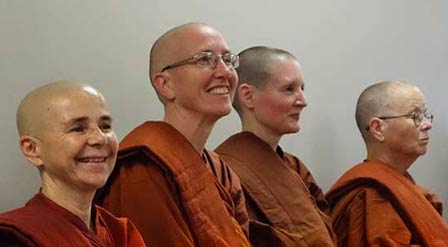

Garling acknowledges that not so much progress has been made for lay women. However, we are in a time of significant progress for the female monastic community, with many ordinations and new communities arising.

Garling acknowledges that not so much progress has been made for lay women. However, we are in a time of significant progress for the female monastic community, with many ordinations and new communities arising. Alliance for Bikkhunis and this magazine itself are reflective of that progress.

Garling tells the stories of many of the women who had prominent places in the life of the Buddha. She has researched their stories in many compilations of suttas, and her writing brings these women to life. We hear not only of the mythological stories, but also of the details that make these women seem very real— not so different from the rest of us, only lucky enough to have lived with and known the Buddha himself.

Most of us are familiar with the most common story of the birth of the Buddha, His mother, Maya, travels to Lumbini. The Buddha emerges from her side (already able to walk) in the presence of a number of male deities. Garling’s research brings to us a much more human story of a young queen. She has been romanced by the king, married and is pregnant. Lumbini is known as a place of pilgrimage and protection for women before and during in childbirth. Maya’s sister is there and assists her as the child is born. The Buddha was a human being; this is a very human birth, facilitated and supported by the women’s community.

There are more stories in Garling’s book than it is possible to relate in a review — one needs to read the book. For this reader, it was a delightful experience to be immersed in the women’s half of the four fold sangha.

Garling reminds us that the “sacred feminine” is an important aspect of the Buddha’s story. His time was a time of matriarchal deities, and the goddesses were present for him at critical points in his growing up and awakening process.

Perhaps two other stories of note. Garling reminds us that the “sacred feminine” is an important aspect of the Buddha’s story. His time was a time of matriarchal deities, and the goddesses were present for him at critical points in his growing up and awakening process. She makes particular reference to the presence of the goddess Abaya at his birth and that the child was taken to her temple shortly after his birth to pay reverence.

Although many of the women — wife, mother, members of the harem — who have lay lives through much of the life of the Buddha, nearly all of them become nuns and then are lost to view. Garling does, however include the story of Visakha, who is a lay woman. She was an accomplished practitioner, a wife, mother, grandmother, an advisor to the Buddha. As a laywoman, I was delighted to find her in this collection of stories. Garling says she lived, “juggling faith and family with joyful ease.” Just that should be an inspiration for most of us, nuns and laywomen! She also lived very much in control of her own life, insisting on being able to practice (contrary to the wishes of her father-in-law) and eventually bringing members of her husband’s family to the Buddha. As I read some of the details of her story, I found that I wanted to spend more time with her and to teach her story to my classes in the lay Buddhist world.

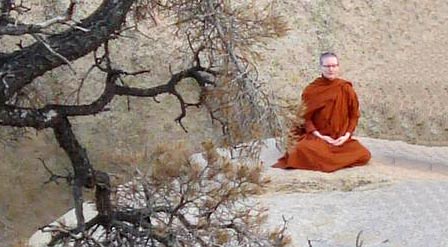

We should all be encouraged by the teaching of this book. We are each one of us — monks, nuns, women, men— able to seek and to find liberation for ourselves. We do not have to wait for another birth, in another body.

There were women present throughout the life of the Buddha. And in the end, as Garling reminds us, he reminds Mara that he would not die until all four groups of the sangha were engaged in teaching the Dharma to others. Mara reminds him that this has come to pass, and shortly thereafter the Buddha dies. Garling says, “In the forty-five years since his enlightenment, he had laid a firm foundation for women and men to seek liberation for themselves. Now it was up to them.”

We should all be encouraged by the teaching of this book. We are each one of us — monks, nuns, women, men— able to seek and to find liberation for ourselves. We do not have to wait for another birth, in another body. This body, this incarnation is enough. All we have to do is to go to work!

About the Author

Mary Grace Orr has practiced vipassana since 1983. Prior to that she followed western contemplative practices; she worked as a therapist from 1977 to 1995. She was trained to teach by Jack Kornfield. Currently Mary Grace lives in Hawaii, and teaches retreats at Spirit Rock and throughout the United States.

There were women there. Really.

Most of us who have studied, practiced and read about Buddhism and the life of the Buddha have hardly noticed their presence. His life and time, and the subsequent thrust of his teachings have seemed overwhelmingly male and largely monastic. Although in his teachings he provided us with the model of the fourfold sangha (monks, nuns, lay men and lay women), the female half of that sangha has largely been ignored and held to a less significant place.

Wendy Garling’s book, Stars at Dawn, is a refreshing rejoinder to that picture. She reminds us in the beginning that the Buddha taught that, “all believers in his faith — women and men, lay and ordained, would become wise and accomplished through his teachings…” (p. 1)

Garling acknowledges that not so much progress has been made for lay women. However, we are in a time of significant progress for the female monastic community, with many ordinations and new communities arising.

Garling acknowledges that not so much progress has been made for lay women. However, we are in a time of significant progress for the female monastic community, with many ordinations and new communities arising. Alliance for Bikkhunis and this magazine itself are reflective of that progress.

Garling tells the stories of many of the women who had prominent places in the life of the Buddha. She has researched their stories in many compilations of suttas, and her writing brings these women to life. We hear not only of the mythological stories, but also of the details that make these women seem very real— not so different from the rest of us, only lucky enough to have lived with and known the Buddha himself.

Most of us are familiar with the most common story of the birth of the Buddha, His mother, Maya, travels to Lumbini. The Buddha emerges from her side (already able to walk) in the presence of a number of male deities. Garling’s research brings to us a much more human story of a young queen. She has been romanced by the king, married and is pregnant. Lumbini is known as a place of pilgrimage and protection for women before and during in childbirth. Maya’s sister is there and assists her as the child is born. The Buddha was a human being; this is a very human birth, facilitated and supported by the women’s community.

There are more stories in Garling’s book than it is possible to relate in a review — one needs to read the book. For this reader, it was a delightful experience to be immersed in the women’s half of the four fold sangha.

Garling reminds us that the “sacred feminine” is an important aspect of the Buddha’s story. His time was a time of matriarchal deities, and the goddesses were present for him at critical points in his growing up and awakening process.

Perhaps two other stories of note. Garling reminds us that the “sacred feminine” is an important aspect of the Buddha’s story. His time was a time of matriarchal deities, and the goddesses were present for him at critical points in his growing up and awakening process. She makes particular reference to the presence of the goddess Abaya at his birth and that the child was taken to her temple shortly after his birth to pay reverence.

Although many of the women — wife, mother, members of the harem — who have lay lives through much of the life of the Buddha, nearly all of them become nuns and then are lost to view. Garling does, however include the story of Visakha, who is a lay woman. She was an accomplished practitioner, a wife, mother, grandmother, an advisor to the Buddha. As a laywoman, I was delighted to find her in this collection of stories. Garling says she lived, “juggling faith and family with joyful ease.” Just that should be an inspiration for most of us, nuns and laywomen! She also lived very much in control of her own life, insisting on being able to practice (contrary to the wishes of her father-in-law) and eventually bringing members of her husband’s family to the Buddha. As I read some of the details of her story, I found that I wanted to spend more time with her and to teach her story to my classes in the lay Buddhist world.

We should all be encouraged by the teaching of this book. We are each one of us — monks, nuns, women, men— able to seek and to find liberation for ourselves. We do not have to wait for another birth, in another body.

There were women present throughout the life of the Buddha. And in the end, as Garling reminds us, he reminds Mara that he would not die until all four groups of the sangha were engaged in teaching the Dharma to others. Mara reminds him that this has come to pass, and shortly thereafter the Buddha dies. Garling says, “In the forty-five years since his enlightenment, he had laid a firm foundation for women and men to seek liberation for themselves. Now it was up to them.”

We should all be encouraged by the teaching of this book. We are each one of us — monks, nuns, women, men— able to seek and to find liberation for ourselves. We do not have to wait for another birth, in another body. This body, this incarnation is enough. All we have to do is to go to work!

About the Author

Mary Grace Orr has practiced vipassana since 1983. Prior to that she followed western contemplative practices; she worked as a therapist from 1977 to 1995. She was trained to teach by Jack Kornfield. Currently Mary Grace lives in Hawaii, and teaches retreats at Spirit Rock and throughout the United States.